By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

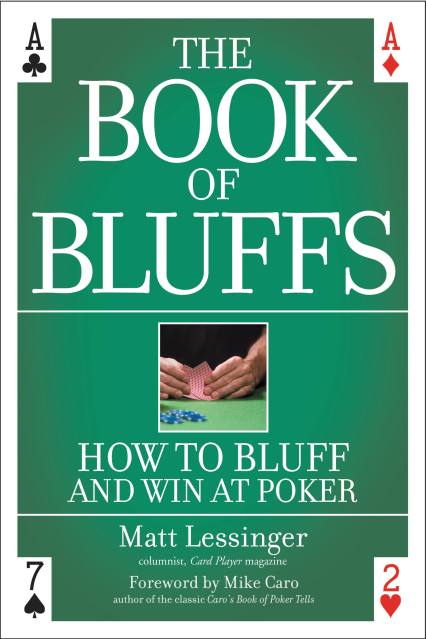

The Book of Bluffs

How to Bluff and Win at Poker

Contributors

Foreword by Mike Caro

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 31, 2007

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446507158

Price

$7.99Price

$9.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $7.99 $9.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 31, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Twenty years ago, Mike Caro wrote the book on what to look for in a player’s movements, gestures, and facial expressions—their “tells”—to determine if they were bluffing, and it remains one of the bestselling poker books of all time. But what Caro didn’t do was teach players how to bluff. Enter Matt Lessinger, a professional poker player and columnist, who in THE BOOK OF BLUFFS shows players how to get their opponents to fold—no matter how strong a hand they’ve been dealt. Lessinger reveals how, with the correct timing and artistry, bluffing will allow a player to win while holding an inferior hand—the very essence of poker.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use