By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

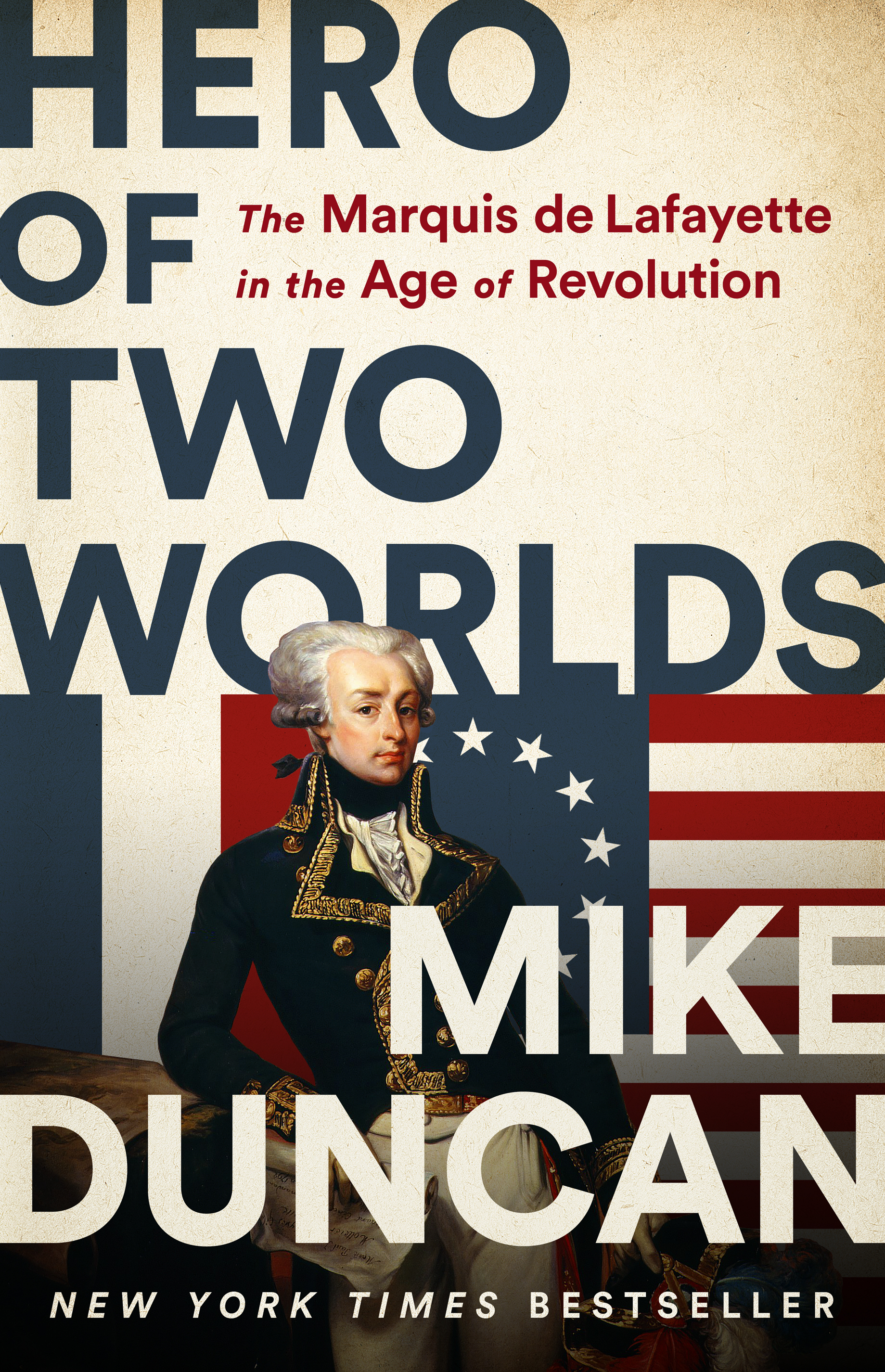

Hero of Two Worlds

The Marquis de Lafayette in the Age of Revolution

Contributors

By Mike Duncan

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 24, 2021

- Page Count

- 512 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541730335

Price

$35.00Price

$46.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $46.00 CAD

- ebook $1.99 $1.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 24, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A #1 ABA INDEPENDENT BOOKSTORE BESTSELLER

From the bestselling author of The Storm Before the Storm and host of the Revolutions podcast comes the “immensely compelling” (The New York Times) story of the Marquis de Lafayette’s lifelong quest to defend the principles of liberty and equality.

Few in history can match the revolutionary career of the Marquis de Lafayette. Over fifty incredible years at the heart of the Age of Revolution, he fought courageously on both sides of the Atlantic. He was a soldier, statesman, idealist, philanthropist, and abolitionist.

As a teenager, Lafayette ran away from France to join the American Revolution. Returning home a national hero, he helped launch the French Revolution, eventually spending five years locked in dungeon prisons. After his release, Lafayette sparred with Napoleon, joined an underground conspiracy to overthrow King Louis XVIII, and became an international symbol of liberty. Finally, as a revered elder statesman, he was instrumental in the overthrow of the Bourbon Dynasty in the Revolution of 1830.

From enthusiastic youth to world-weary old age, from the pinnacle of glory to the depths of despair, Lafayette never stopped fighting for the rights of all mankind. His remarkable life is the story of where we come from, and an inspiration to defend the ideals he held dear.

-

“My favorite history book I’ve read this year so far!"Jeff Glor, CBS This Morning: Saturday

-

“Pleasingly informal….Duncan’s biography is written in a loose, colloquial style that sometimes startles with its informality but more often delights with its directness.”Adam Gopnik, The New Yorker

-

“Mr. Duncan’s ‘Hero of Two Worlds’ offers, in readable prose, much informative description alongside measured interpretation. The author’s sympathetic yet balanced and sensible rendering, some may think, mirrors Lafayette’s eventful life in a revolutionary age.”The Wall Street Journal

-

"The Marquis de Lafayette was a revolutionary, but he was also a moderate. Duncan does a fantastic job telling his story, which is a thrilling adventure, one filled with long odds, battles won, and tragic disillusionment."Elliot Ackerman, The Week

-

“[I]n an age of self-indulgent polemics, deranged conspiracy theories, and pervasive disinformation, to listen to Duncan while washing dishes or folding laundry is to believe that facts are knowable, that historical events of immense complexity can be made legible, and—to attempt to answer the question with which I started this review—that history is made neither by singular individuals nor by social forces, but by the idiosyncratic interplay of decisions within well-placed vanguard classes….This is the kind of detail-oriented storytelling that Duncan excels at.”The New Republic

-

“An immensely compelling biography of Lafayette and a disquisition on the limits of bourgeois liberalism.”Jamelle Bouie, The New York Times

-

“Mike Duncan has dug deep into the world of revolutions, and the richness of detail in this book is beguiling. But Mike’s superpower is his storytelling skill. Hero Of Two Worlds hooks you from page one with humor, a sly perspective and a page turning narrative drive worthy of a life like Lafayette’s.”Rian Johnson, award-winning filmmaker

-

“Duncan displays impressive skill in keeping his Lafayette an admirable figure…. An outstanding account of an almost impossibly eventful life.”Kirkus Reviews, starred

-

“Engrossing… Duncan effectively balances Lafayette the man with Lafayette the public figure and helps delineate the relationship between the United States and France….His impressive biography provides an insightful look at the American Revolution that can be appreciated by history lovers and general readers alike.”BookPage

-

"Mike Duncan’s excellent, well-researched book portrays Lafayette’s extraordinary life as a fascinating, transatlantic drama with three great revolutions and transitional interludes that carry the reader through seven explosive decades of historical change. The hero of this drama plays starring public roles in the American Revolution and the French Revolutions of 1789 and 1830. But Duncan weaves the people, conflicts, and legacies of these vast public events into stories about a personal life that was always entangled with complex family networks and multi-generational friendships as well as a loving marriage and emotionally-charged relationships with other women."Lloyd Kramer, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and author of Lafayette in Two Worlds: Public Cultures and Personal Identities in an Age of Revolutions

-

“Lafayette gets his due in this magisterial biography.”Parade.com

-

“Comprehensive and accessible…. Duncan marshals a wealth of information into a crisp and readable narrative. This sympathetic portrait illuminates the complexities of Lafayette and his revolutionary era.”Publishers Weekly

-

"Historian and popular history podcaster Duncan brings Lafayette to center stage in a carefully researched biography… [he] offers solid historical research in a hip, humorous, and appealing voice."Booklist

-

“This is just great writing. Duncan really knows how to assemble a compelling story and with Lafayette he has an amazing subject with which to work. Restores some of the well-deserved luster to the Frenchman’s historical reputation.”Dan Carlin, host of Hardcore History

-

"I first learned of Mike Duncan's work when a prominent politician told me he'd been addicted to his podcast on the French Revolution, and found it startlingly relevant in 2021. Duncan's work is a reminder that history can also be a gripping yarn full of compelling characters, and in Hero of Two Worlds he brings alive one of the great characters of American history."Ben Smith, New York Times

-

“Duncan reintroduces a celebrated hero….A highly readable biography of a committed liberal activist caught up in the fickle political passions of revolutionary extremism, violence, and war. Like Duncan's previous work, this book is engaging and accessible.”Library Journal

-

"All listeners of The History of Rome and Revolutions – as well as readers of The Storm Before The Storm -- know the joy of Mike Duncan guiding them through epic, operatic moments in western history. Now Duncan has zeroed in on his perfect subject, a towering figure through whom Duncan can explore and even upend the birth of political liberalism. Duncan has reintroduced the Marquis de Lafayette for a whole new generation, bringing him to life with all his passions, contradictions and hypocrisies. Never mind the Broadway musicals, here's the Hero of Two Worlds."Spencer Ackerman, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author of Reign of Terror: How The 9/11 Era Destabilized America and Produced Trump

-

"Mike Duncan's ability to weave a rich and compelling story is on full display in Hero of Two Worlds. He takes the reader on a gripping roller-coaster ride that follows the Marquis de Lafayette's fortunes through decades of victory, defeat, and revolution on two continents… Duncan has an exceptional eye for both human potential and human fallibility, grasping the qualities that make figures like Lafayette real, three-dimensional people, simultaneously victims of circumstance and active participants driving forward the course of history. Hero of Two Worlds is biography and narrative at its best, an informative page-turner crafted by a master of historical storytelling."Patrick Wyman, creator of Tides of History and author of The Verge: Reformation, Renaissance, and Forty Years that Shook the World

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use