By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

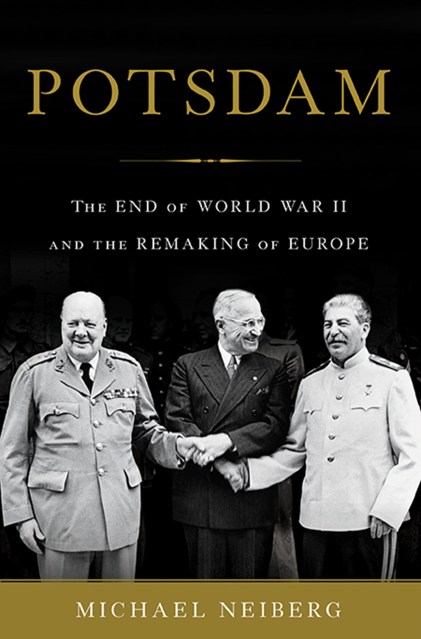

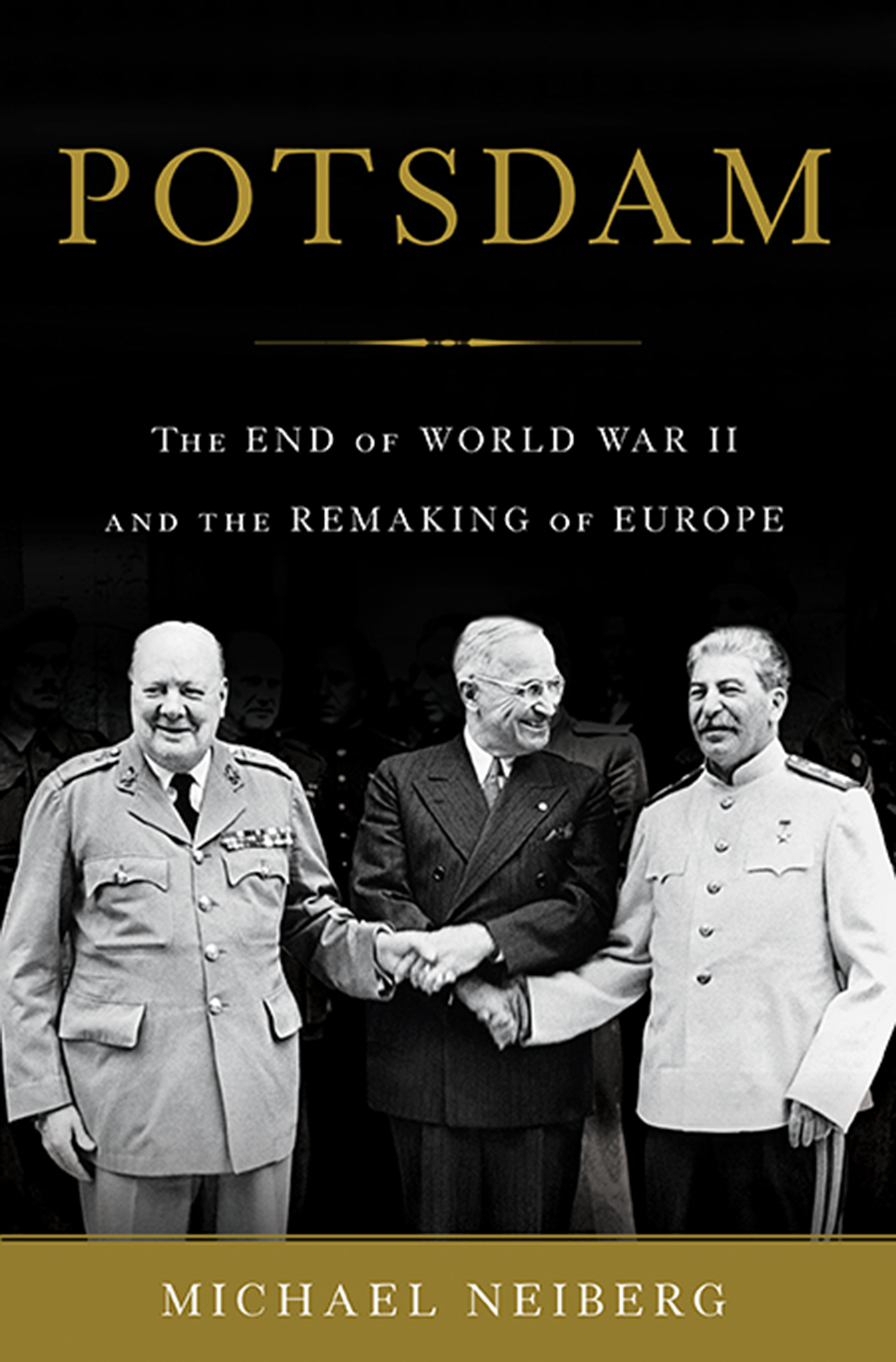

Potsdam

The End of World War II and the Remaking of Europe

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 5, 2015

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465040629

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Hardcover $38.00 $48.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 5, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

After Germany’s defeat in World War II, Europe lay in tatters. Millions of refugees were dispersed across the continent. Food and fuel were scarce. Britain was bankrupt, while Germany had been reduced to rubble. In July of 1945, Harry Truman, Winston Churchill, and Joseph Stalin gathered in a quiet suburb of Berlin to negotiate a lasting peace: a peace that would finally put an end to the conflagration that had started in 1914, a peace under which Europe could be rebuilt.

The award-winning historian Michael Neiberg brings the turbulent Potsdam conference to life, vividly capturing the delegates’ personalities: Truman, trying to escape from the shadow of Franklin Roosevelt, who had died only months before; Churchill, bombastic and seemingly out of touch; Stalin, cunning and meticulous. For the first week, negotiations progressed relatively smoothly. But when the delegates took a recess for the British elections, Churchill was replaced-both as prime minster and as Britain’s representative at the conference-in an unforeseen upset by Clement Attlee, a man Churchill disparagingly described as “a sheep in sheep’s clothing.” When the conference reconvened, the power dynamic had shifted dramatically, and the delegates struggled to find a new balance. Stalin took advantage of his strong position to demand control of Eastern Europe as recompense for the suffering experienced by the Soviet people and armies. The final resolutions of the Potsdam Conference, notably the division of Germany and the Soviet annexation of Poland, reflected the uneasy geopolitical equilibrium between East and West that would come to dominate the twentieth century.

As Neiberg expertly shows, the delegates arrived at Potsdam determined to learn from the mistakes their predecessors made in the Treaty of Versailles. But, riven by tensions and dramatic debates over how to end the most recent war, they only dimly understood that their discussions of peace were giving birth to a new global conflict.

-

"Potsdam is a thought-provoking book with many noteworthy perceptions and much good description."New Criterion

-

"[A] well-researched, perceptive history."America in World War II

-

"[Neiberg is] a skilled storyteller."Weekly Standard

-

"[A] crisp, elegantly organized account of Potsdam.... [An] excellent book."Financial Times

-

"An easily digestible page-turner."Wall Street Journal

-

"An intriguing and readable book about a conference that has been relegated to footnotes for much too long. A must-have account for everyone."Library Journal

-

"[A] thoughtful, mildly controversial account.... Neiberg's insightful history makes a case that Potsdam worked much better than Versailles had in 1919."Publishers Weekly

-

"This is a solid account of the conference, concisely summarizing its results and significance without excessive indulgence in entertaining personal anecdotes. Fills a hitherto surprisingly empty niche in the World War II library."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Michael Neiberg has given us a taut, masterful account of Potsdam, revealing that the Big Three operated more from fear-of each other, of their peoples, of their rivals, and of fast-moving events on the ground---than from any degree of confidence or certainty. The Cold War was born at Potsdam, and Neiberg seats us at the conference table, to feel the tension and acrimony."Geoffrey Wawro, author of A Mad Catastrophe: The Outbreak of World War I and the Collapse of the Habsburg Empire

-

"The Potsdam Conference defined international relations in the second half of the twentieth century, and it continues to influence contemporary events in Europe and East Asia. This book offers a compelling account of the events that led to the conference, the personalities who dominated the conference, and the consequences of their decisions. Neiberg explains why Potsdam was more successful than the Versailles Conference at the end of the First World War, and he analyzes how Potsdam contributed to postwar peace. This is a powerful book with high drama--a must-read for anyone interested in global affairs."Jeremi Suri, author of Liberty's Surest Guardian: American Nation-Building from the Founders to Obama

-

"Michael Neiberg's Potsdam is a masterpiece of much needed compression on the Potsdam Conference of 1945, and the contrast with peacemaking in 1919 is excellently brought out."Norman Stone, author of World War Two: A Short History

-

"Ghosts and hopes informed the 1945 Potsdam Conference, which began a new era in European and world history. Michael Neiberg's comprehensively researched, smoothly presented analysis demonstrates that the statesmen who met at Potsdam were as much concerned with ending the era of total war that began in 1914 as with addressing the question of how best to go forward in securing peace and stability. Potsdam describes the processes and consequences in a perceptive work confirming the author's status as a leading scholar of the twentieth century experience."Dennis Showalter, professor of history, Colorado College

-

"With the end of war in Europe in May 1945, Truman, Stalin, Churchill, and their advisors met at Potsdam to solve the 'German problem' once and for all. They agreed upon the main task, but on little else. Shrewdly and economically, Michael Neiberg delineates the conflicting motives and interests that separated the leaders of 'the Big Three.' Mr. Neiberg provides deft pen portraits of the principals as well. He has taken an enormously complicated subject and made it comprehensible for the general reader."Jonathan Schneer, author of Ministers at War: Winston Churchill and His War Cabinet

-

"Although the Potsdam Conference isn't as famous as those held at Casablanca, Quebec, or Yalta, Michael Neiberg brilliantly shows how the decisions made at Potsdam color today's world far more than its counterparts. With compelling prose and first-class scholarship, Neiberg superbly captures its spirit of misplaced optimism, as the world teetered on the brink of a totally unnecessary Cold War."Andrew Roberts, author of The Storm of War: A New History of the Second World War

-

"A first rate account of a meeting that played a key role in defining the postwar world. Scholarly, thoughtful, and well written."Jeremy Black, author of Rethinking World War Two