Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

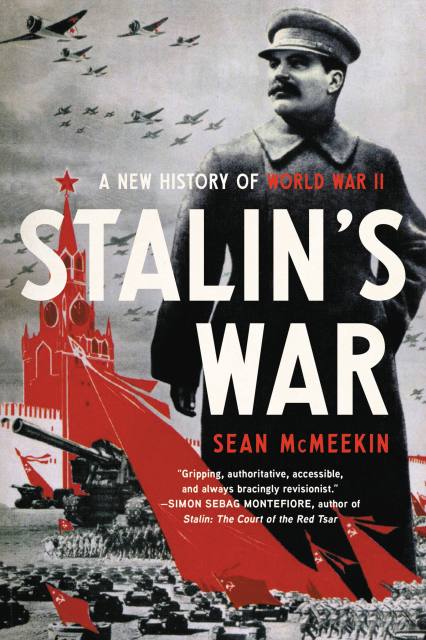

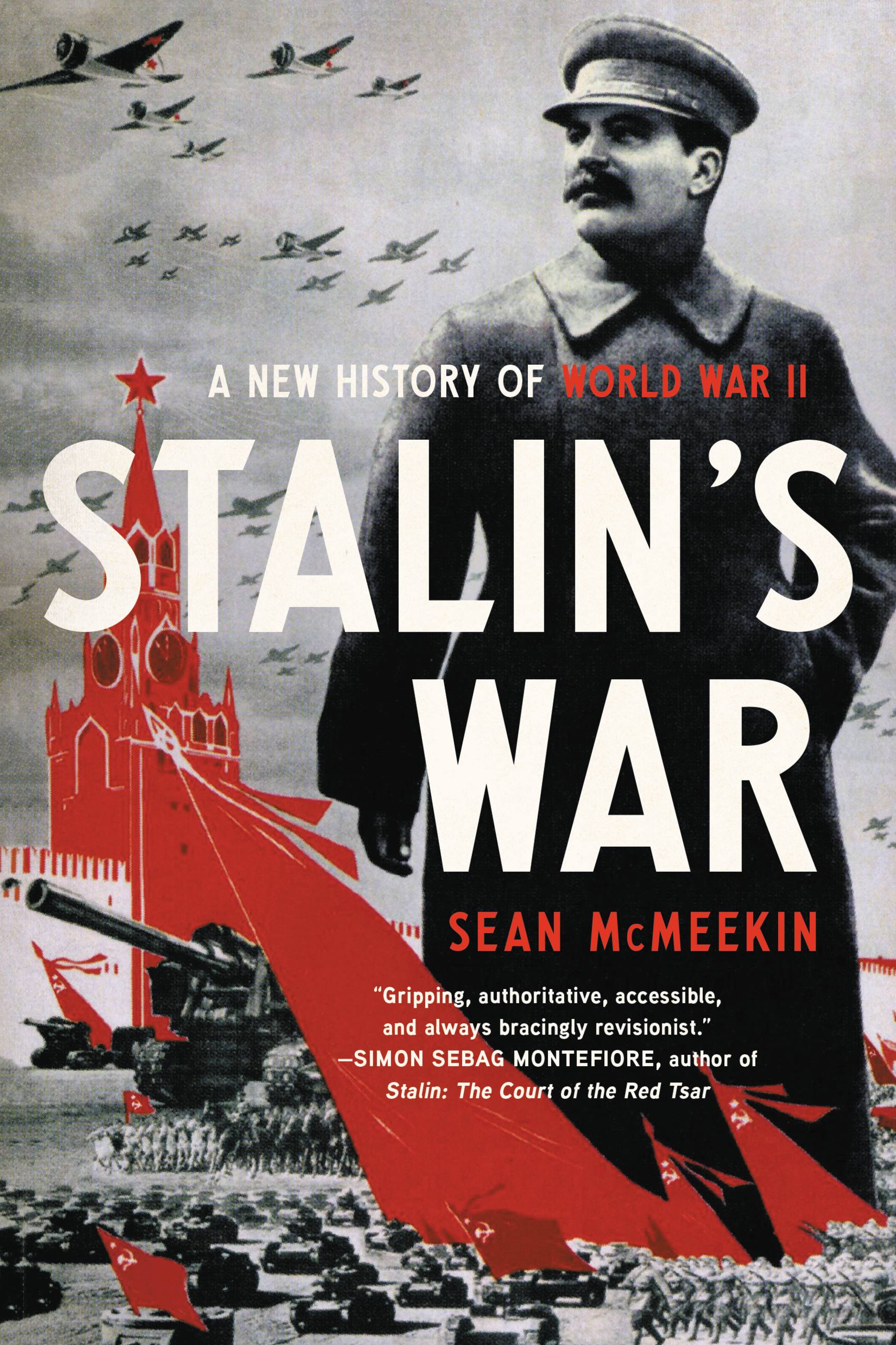

Stalin’s War

A New History of World War II

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 29, 2022

- Page Count

- 880 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541672789

Price

$25.99Price

$34.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $25.99 $34.99 CAD

- Digital download $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $40.00 $50.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $44.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 29, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“A provocative, revisionist take on the Second World War” (Financial Times) by a prize-winning historian

We remember World War II as a struggle between good and evil, with Hitler propelling events and the Allied powers saving the day. But Hitler’s armies did not fight in multiple theaters, his empire did not span the Eurasian continent, and he did not inherit the spoils of war. That role belonged to Joseph Stalin. Hitler’s genocidal ambition may have unleashed Armageddon, but as celebrated historian Sean McMeekin shows, the conflicts that emerged were distinctly shaped by Stalin’s maneuverings, orchestrated to unleash a war between Germany and her capitalist adversaries in Europe and between Japan and the “Anglo-Saxon” powers in Asia. Meanwhile, the United States and Britain’s self-defeating strategy of supporting Stalin and his armies at all costs allowed the Soviets to conquer most of Eurasia, from Berlin to Beijing, for Communism.

A groundbreaking reassessment, Stalin’s War is essential reading for anyone looking to understand the roots of the current world order.

-

“The volume is impressive even by the standard of histories of the second world war…The book is well researched and very well written. It puts forward new ideas and revives some old ones to challenge current mainstream interpretations of the conflict… a new look at the conflict, which poses new questions and, one should add, provides new and often unexpected answers to the old ones.”Guardian

-

“McMeekin is a superb writer. There isn’t a boring page in the book. His familiarity with the archives of several countries is extraordinary.”The Times (UK)

-

“This remarkable book… meticulously researched, elegantly written… Stalin’s War is that rare thing: a book that forces us to think again, and to challenge our narrative of that most well-trodden subject.”BBC History Magazine

-

“In considering the war from a global perspective and shifting the focus from a Eurocentric view, he [McMeekin] provides a refreshing corrective that takes in areas of the war often overlooked by westerners.”The Spectator (UK)

-

“A provocative revisionist take on the Second World War...an accomplished, fearless, and enthusiastic ‘myth buster’...McMeekin is a formidable researcher, working in several languages, and he is prepared to pose the big questions and make judgments….The story of the war itself is well told and impressive in its scope, ranging as it does from the domestic politics of small states such as Yugoslavia and Finland to the global context. It reminds us, too, of what Soviet ‘liberation’ actually meant for eastern Europe….McMeekin is right that we have for too long cast the second world war as the good one. His book will, as he must hope, make us re-evaluate the war and its consequences.”Financial Times

-

“Brilliantly inquisitive.”National Review

-

“Criticisms of the British for living in a Second World War past are frequent. Sean McMeekin, professor of history at Bard College and a talented scholar of the First World War, takes an alternative view by arguing that we are generally living in the wrong war. Drawing on an impressive array of international archives, McMeekin…directs attention to Soviet activity….The book is pertinent because of the extent to which modern cultural wars draw on historicised identities and historical controversies.”The Critic (UK)

-

“Impressively researched and well-written.”Washington Examiner

-

“Indispensable… There are new books every year that promise ‘a new history’ of such a well-studied subject as World War II, but McMeekin actually delivers on that promise.”Christian Science Monitor

-

“McMeekin writes well and has the language skills to comb through a huge amount of archival material… There is much interesting detail about allied supplies to Russia, the Warsaw Uprising of August 1944, the Soviet plunder of Germany in 1945, and the war with Japan.”Irish Times

-

“Based on a vast amount of research.”Prospect (UK)

-

“Fast-paced and well-written … A gifted writer and a talented polemicist.”Inside Story

-

“Historian McMeekin (The Russian Revolution) draws from recently opened Soviet archives to shed light on Stalin’s dark reasoning and shady tactics....Packed with incisive character sketches and illuminating analyses of military and diplomatic maneuvers, this is a skillful and persuasive reframing of the causes, developments, and repercussions of WWII.”Publishers Weekly

-

“Often thought of as 'Hitler's War,' the Second World War is here reexamined with Russian documents that only recently became available....The book pulls no punches in describing the many atrocities, including those against Poles and Germans, that Soviet troops committed....Thoroughly researched.”Library Journal

-

“[A] well-written book…the product of massive research involving every detail of the war. Stalin is intimately painted in all his colours.”Eurasia Review

-

“A sweeping reassessment of World War II seeking to ‘illuminate critical matters long obscured by the obsessively German-centric literature’ on the subject....Yet another winner for McMeekin, this also serves as a worthy companion to Niall Ferguson’s The Pity of War, which argued that Britain should not have entered World War I. Brilliantly contrarian history.”Kirkus

-

“Sean McMeekin’s revisionist Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II isn’t just one of the most compelling histories written about the war this year, it’s one of the best ever. I doubt anyone who reads it will think about the Second World War in the same way.”David Harsanyi, The Federalist's Notable Books of 2021

-

“The ambitious sweep of Hastings, Roberts and Beevor, but much else besides… McMeekin chooses to see Stalin as the central figure in the conflict, rather than Hitler.”Ian Thomson, The Tablet

-

“McMeekin’s book is, on top of making for great reading, a timely reminder that victory in a war does not end geopolitical competition and international conflict.”Jakub Grygiel, Law & Liberty

-

“Stalin’s War is a magnificent book and everyone interested in the causes and consequences of World War II—and what reasonable person could not be?—should read it.”David Gordon, Mises Wire

-

“An independent-minded and immensely learned historian, McMeekin demonstrates the extent of Soviet brutality and treachery before and during WWII.”Paul Gottfried, Chronicles

-

"McMeekin’s Stalin’s War is such a mind-blowing assault on the conventional narrative that I’m fairly certain it’s not even legal."Austin Bramwell, former trustee of the National Review

-

“In the eyes of many Russians today, the Soviet Union’s victory in World War Two still legitimizes Josef Stalin’s bloody dictatorship. In this brilliant and provocative history, Sean McMeekin takes on Stalin’s legend, demonstrating, among other things, that the Western allies, and especially the United States, were far more critical to Stalin’s victory than Soviet propaganda then or later would ever acknowledge. This book will change the way readers understand Stalin’s War.”Walter Russell Mead, Global View Columnist, Wall Street Journal

-

“Gripping, authoritative, accessible, and always bracingly revisionist.”Simon Sebag Montefiore, author of Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar

-

“Stalin’s War is above all about strategy: the failure of Roosevelt and Churchill to make shrewd choices as World War II played out. McMeekin brilliantly argues that instead of weighting the European and Pacific theaters to favor their own interests—and to weaken the inevitably antagonistic Soviet Union—FDR and Churchill left the most critical parts of Asia unguarded while they ground down the German army, a decision that favored Stalin's interests far more than their own. Roosevelt’s ‘Germany first’ strategy and the trillion dollars of Lend Lease aid he poured into Stalin's treasury would underwrite Soviet control of China and East Central Europe after 1945 and hatch a Cold War whose dire effects are with us still.”Geoffrey Wawro, author of Sons of Freedom and director of the University of North Texas Military History Center

-

“Sean McMeekin’s approach in Stalin’s War is both original and refreshing, written as it is with a wonderful clarity.”Antony Beevor, author of Stalingrad

-

“Sean McMeekin’s new book fills a massive gap in the historiography of World War II. Based on exhaustive research in Russian and other archives, this examination of Stalin’s foreign policy explores fresh avenues and explodes many myths, perhaps the most significant being that of unwittingly exaggerated emphasis on ‘Hitler’s war.’ McMeekin shows conclusively that the two tyrants were equally responsible, both for the outbreak of war in 1939 and the appalling slaughter which ensued.”Nikolai Tolstoy