By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

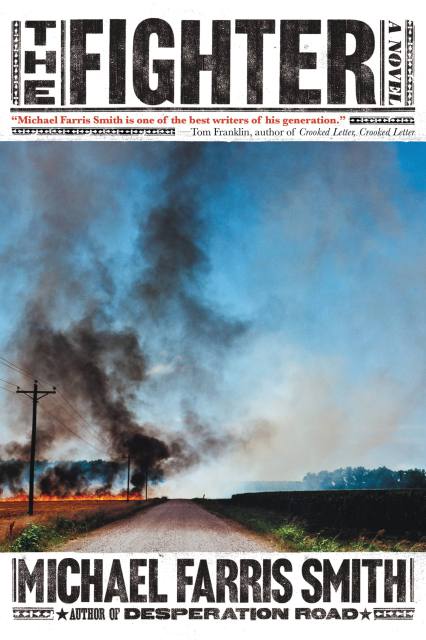

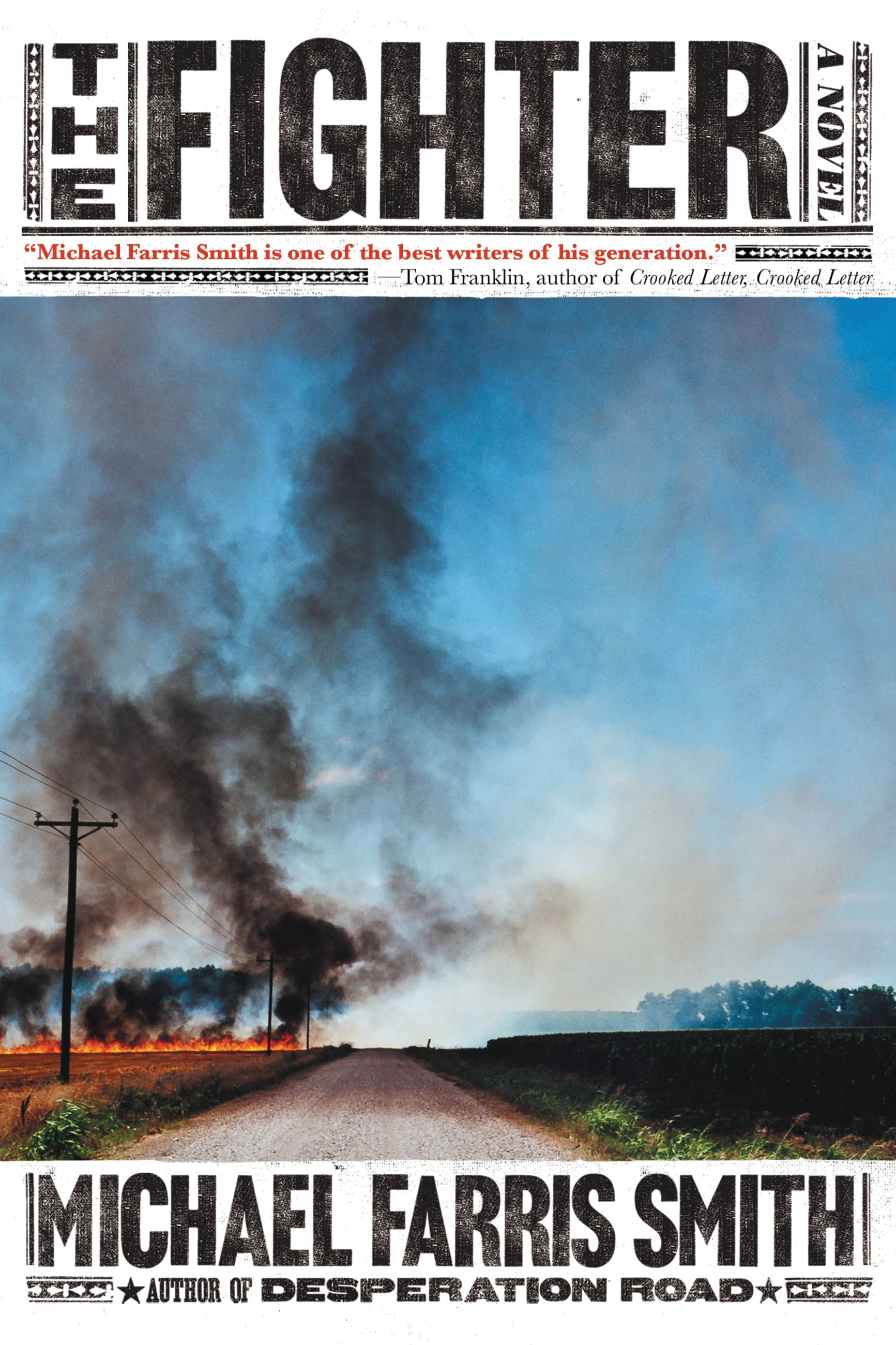

The Fighter

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 20, 2018

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316432337

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 20, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Now a major motion picture and titled for the screen as RUMBLE THROUGH THE DARK; a blistering tale of violence and deliverance set against the mythic backdrop of the Mississippi Delta.

The acres and acres of fertile soil, the two-hundred-year-old antebellum house, all gone. And so is the woman who gave it to Jack, the foster mother only days away from dying, her mind eroded by dementia, the family legacy she entrusted to Jack now owned by banks and strangers.

And Jack's mind has begun to fail, too. The decades of bare-knuckle fighting are now taking their toll, as concussion after concussion forces him to carry around a stash of illegal painkillers and a notebook of names that separates friend from foe. But in a single twisted night, Jack loses his chance to win it all back. Hijacked by a sleazy gambler out to settle a score, Jack is robbed of the money that will clear his debt with Big Momma Sweet — the queen of Delta vice, whose deep backwoods playground offers sin to all those willing to pay — and open a path that could lead him back home. Yet this sudden reversal of fortunes introduces an unlikely savior in the form of a sultry, tattooed carnival worker.

Guided by what she calls her "church of coincidence," Annette pushes Jack toward redemption, only to discover that the world of Big Momma Sweet is filled with savage danger. Damaged by regret, crippled by twenty-five years of fists and elbows, heartbroken by his own betrayals, Jack is forced to step into the fighting pit one last time, the stakes nothing less than life or death. With the raw power and poetry of a young Larry Brown and the mysticism of Cormac McCarthy, Michael Farris Smith cements his place as one of the finest writers in the American literary landscape.

The acres and acres of fertile soil, the two-hundred-year-old antebellum house, all gone. And so is the woman who gave it to Jack, the foster mother only days away from dying, her mind eroded by dementia, the family legacy she entrusted to Jack now owned by banks and strangers.

And Jack's mind has begun to fail, too. The decades of bare-knuckle fighting are now taking their toll, as concussion after concussion forces him to carry around a stash of illegal painkillers and a notebook of names that separates friend from foe. But in a single twisted night, Jack loses his chance to win it all back. Hijacked by a sleazy gambler out to settle a score, Jack is robbed of the money that will clear his debt with Big Momma Sweet — the queen of Delta vice, whose deep backwoods playground offers sin to all those willing to pay — and open a path that could lead him back home. Yet this sudden reversal of fortunes introduces an unlikely savior in the form of a sultry, tattooed carnival worker.

Guided by what she calls her "church of coincidence," Annette pushes Jack toward redemption, only to discover that the world of Big Momma Sweet is filled with savage danger. Damaged by regret, crippled by twenty-five years of fists and elbows, heartbroken by his own betrayals, Jack is forced to step into the fighting pit one last time, the stakes nothing less than life or death. With the raw power and poetry of a young Larry Brown and the mysticism of Cormac McCarthy, Michael Farris Smith cements his place as one of the finest writers in the American literary landscape.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use