By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

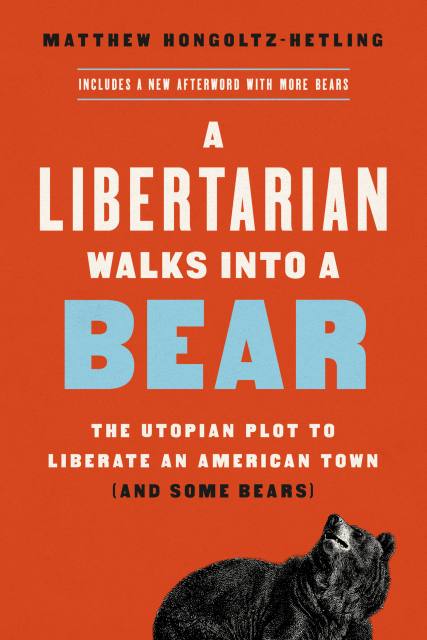

A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear

The Utopian Plot to Liberate an American Town (And Some Bears)

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 15, 2020

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541788480

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 15, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A tiny American town's plans for radical self-government overlooked one hairy detail: no one told the bears.

Once upon a time, a group of libertarians got together and hatched the Free Town Project, a plan to take over an American town and completely eliminate its government. In 2004, they set their sights on Grafton, NH, a barely populated settlement with one paved road. When they descended on Grafton, public funding for pretty much everything shrank: the fire department, the library, the schoolhouse. State and federal laws became meek suggestions, scarcely heard in the town's thick wilderness.

The anything-goes atmosphere soon caught the attention of Grafton's neighbors: the bears. Freedom-loving citizens ignored hunting laws and regulations on food disposal. They built a tent city in an effort to get off the grid. The bears smelled food and opportunity.

A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear is the sometimes funny, sometimes terrifying tale of what happens when a government disappears into the woods. Complete with gunplay, adventure, and backstabbing politicians, this is the ultimate story of a quintessential American experiment — to live free or die, perhaps from a bear.

The anything-goes atmosphere soon caught the attention of Grafton's neighbors: the bears. Freedom-loving citizens ignored hunting laws and regulations on food disposal. They built a tent city in an effort to get off the grid. The bears smelled food and opportunity.

A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear is the sometimes funny, sometimes terrifying tale of what happens when a government disappears into the woods. Complete with gunplay, adventure, and backstabbing politicians, this is the ultimate story of a quintessential American experiment — to live free or die, perhaps from a bear.

-

"[A] witty and precisely observed debut....Hongoltz-Hetling skillfully probes shortcomings and ironies in the libertarian philosophy....The result is an entertaining and incisive portrait of political ideology run amok."Publishers Weekly

-

"An entertaining sendup of idealistic politics and the fatal flaws of overweening self-interest."Kirkus

-

"[Hongoltz-Hetling] reconstructs a remarkable, and remarkably strange, episode in recent history....The resulting narrative is simultaneously hilarious, poignant, and deeply unsettling."The New Republic

-

"Every once in a while, a book comes along that is so darkly comedic, with such a defined sense of place and filled with characters that range from the fascinating to the bizarre to the earnest, that partway through reading, it hits you: This has got to become a Coen brothers movie...Hongoltz-Hetling is a master of the turn of phrase. His voice is breezy and critical, with a finely tuned eye aimed at the absurdities as well as at the earnestness of the Free Town Project."Star Tribune

-

"Since the beginning, Americans have been fighting about the balance between individual liberty and the common good. Hongoltz-Hetling shows what can happen when one rural New Hampshire town went to the libertarian extreme in this madcap tale that zig-zags between tragedy and farce, with the possibility of being eaten."Colin Woodard, New York Times-bestselling author of American Nations and Union

-

"A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear is a finely drawn portrait of one freedom-loving town, and a joyful romp through the dark corners of the American psyche. Matthew Hongoltz-Hetling is a gifted writer with a high-powered radar for the strange details of American life. He skillfully portrays the dreamers and eccentrics who populate Grafton, and the bears lurking just beyond its treelines. At turns hilarious and alarming, this story had me firmly in its jaws from the opening pages."Evan Ratliff, author of The Mastermind

-

"Matthew Hongoltz-Hetling's wild and wonderful blend of small-town America and large-scale ideals, imparted with humor and insight reminiscent of Sarah Vowell and Bill Bryson, is an unpredictable and endlessly fascinating feat of immersive reporting, filled with singular characters and doughnut-eating bears."Michael Finkel, bestselling author of The Stranger in the Woods

-

“An alarming, eyebrow-raising and often hilarious true life tale of what happens when a fringe political ideology clashes with the real world, in ways which incorporate economics, conservation, zoology, parasitology, environmentalism, various types of psychology and animal behaviour studies, and more.”BBC Science Focus

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use