By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

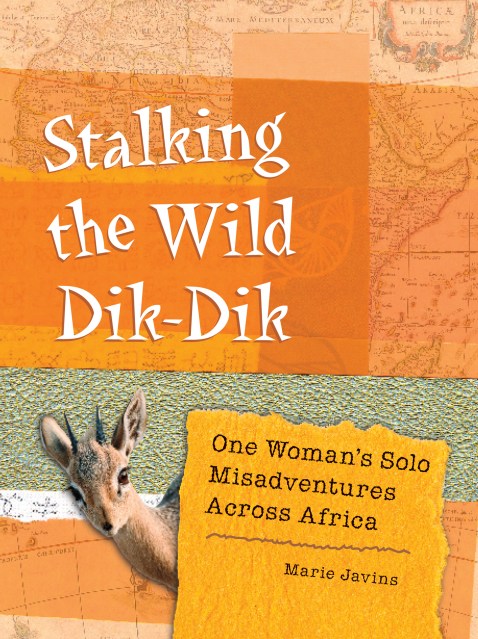

Stalking the Wild Dik-Dik

One Woman's Solo Misadventures Across Africa

Contributors

By Marie Javins

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 20, 2009

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780786747931

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $10.99 $13.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 20, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Stalking the Wild Dik-Dik is a spirited African adventure of a solo woman traveler whose overland excursion across the continent includes challenges, inevitable mishaps, and more than a few debacles.

Author and world traveler Marie Javins is an unflappable narrator, who takes even the most bizarre and patience-trying situations with a dose of good humor. Javins fell in love with Africa when she traversed the continent in 2001 as part of a larger world tour. She later returned to spend half of 2005 revisiting the people and places that had so impacted her on her first trip. Javins was struck not by the desperation of Africa, but by its hope — the dignity of its people, the vibrancy of its cities, and the inherent adventure that is inherent it offered.

Stalking the Wild Dik-Dik is a funny and compassionate account of the sort of lively and heedless undertaking that could only happen in Africa. Javins’s brushes with wildlife are punctuated with more serious dilemmas. Through it all, Javins’s experience of Africa is life-altering, and her witty observations make for the best kind of travel literature which takes its readers into the heart and soul of the continent.

Author and world traveler Marie Javins is an unflappable narrator, who takes even the most bizarre and patience-trying situations with a dose of good humor. Javins fell in love with Africa when she traversed the continent in 2001 as part of a larger world tour. She later returned to spend half of 2005 revisiting the people and places that had so impacted her on her first trip. Javins was struck not by the desperation of Africa, but by its hope — the dignity of its people, the vibrancy of its cities, and the inherent adventure that is inherent it offered.

Stalking the Wild Dik-Dik is a funny and compassionate account of the sort of lively and heedless undertaking that could only happen in Africa. Javins’s brushes with wildlife are punctuated with more serious dilemmas. Through it all, Javins’s experience of Africa is life-altering, and her witty observations make for the best kind of travel literature which takes its readers into the heart and soul of the continent.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use