Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

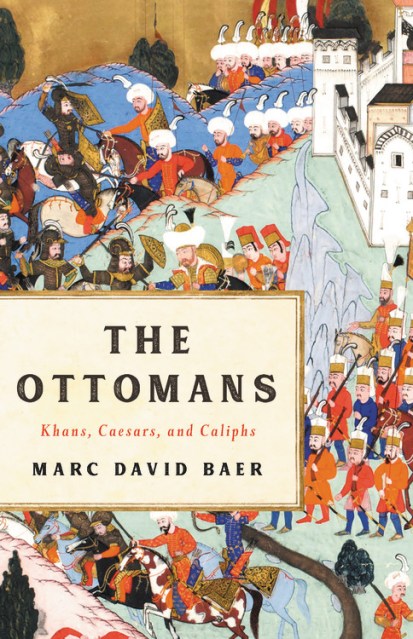

The Ottomans

Khans, Caesars, and Caliphs

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 5, 2021

- Page Count

- 560 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541673809

Price

$35.00Price

$44.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $44.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $32.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 5, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The Ottoman Empire has long been depicted as the Islamic, Asian antithesis of the Christian, European West. But the reality was starkly different: the Ottomans’ multiethnic, multilingual, and multireligious domain reached deep into Europe’s heart. Indeed, the Ottoman rulers saw themselves as the new Romans. Recounting the Ottomans’ remarkable rise from a frontier principality to a world empire, historian Marc David Baer traces their debts to their Turkish, Mongolian, Islamic, and Byzantine heritage. The Ottomans pioneered religious toleration even as they used religious conversion to integrate conquered peoples. But in the nineteenth century, they embraced exclusivity, leading to ethnic cleansing, genocide, and the empire’s demise after the First World War.

The Ottomans vividly reveals the dynasty’s full history and its enduring impact on Europe and the world.

-

“This forceful history takes aim at the notion that the Ottomans represent the antithesis of Western Europe, asking readers ‘to conceptualise a Europe that is not merely Christian.’”New Yorker

-

“Mr. Baer organizes his material according to contemporary concerns…thereby eking out surprisingly fresh insights from this hitherto well-plowed terrain… Highly readable, original and thorough.”Wall Street Journal

-

“Highly readable... Baer’s fine book gives a panoramic and thought-provoking account of over half a millennium of Ottoman and — it now goes without saying — European history.”Guardian

-

"Magnificent… [An] important and hugely readable book — a model of well-written, accessible scholarship."Financial Times

-

“Baer offers a fuller, fresher view of the dynasty that ruled an empire for 500 years and helped shape the West as much as the Habsburgs or Romanovs… A major achievement. [Baer] is a writer in full command of his subject.”Spectator

-

“A winning portrait of seven centuries of empire, teeming with life and colour, human interest and oddity, cruelty and oppression mixed with pleasure, benevolence and great artistic beauty.”Sunday Times

-

“A wildly ambitious and entertainingly lurid history."Times

-

“Sweeping… Baer’s elegantly written narrative is full of bloody state building…along with intriguing, counterintuitive takes on Ottoman culture.”Publishers Weekly

-

“There’s no study more masterful than Baer’s on the lengthy rule of the Ottoman Empire…Baer is especially skilled at presenting extensive information in an engaging and accessible way.”Library Journal

-

“A book as sweeping, colorful, and rich in extraordinary characters as the empire which it describes.”Tom Holland, author of Dominion

-

“A compellingly readable account of one of the great world empires from its origins in thirteenth century to modern times. Drawing on contemporary Turkish and European sources, Marc David Baer situates the Ottomans squarely at the overlap of European and Middle Eastern history. Blending the sacred and the profane, the social and the political, the sublime and the absurd, Baer brings his subject to life in rich vignettes. An outstanding book.”Eugene Rogan, author of The Fall of the Ottomans

-

“A superb, gripping, and refreshing new history—finely written and filled with fascinating characters and analysis—that places the dynasty where it belongs: at the center of European history.”Simon Sebag Montefiore, author of The Romanovs

-

“Marc David Baer’s colorful, readable book is informed by all the newest research on his massive subject. In showing how an epic of universal empire, conquest and toleration turned into the drama of nationalism, crisis, and genocide, he gives us not only an expansive history of the Ottomans, but an expanded history of Europe.”James McDougall, University of Oxford

-

“Marc David Baer’s The Ottomans is a scintillating and brilliantly panoramic account of the history of the Ottoman empire, from its genesis to its dissolution. Baer provides a clear and engaging account of the dynastic and high politics of the empire, whilst also surveying the Ottoman world’s social, cultural, intellectual and economic development. What emerges is an Ottoman Empire that was a direct product of and an active participant in both European and global history. It challenges and transforms how we think of ‘East’ and ‘West,’ ‘Enlightenment,’ and ‘modernity,’ and directly confronts the horrors as well as the achievements of Ottoman rule.”Peter Sarris, University of Cambridge