By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

Tuesday’s Promise

One Veteran, One Dog, and Their Bold Quest to Change Lives

Contributors

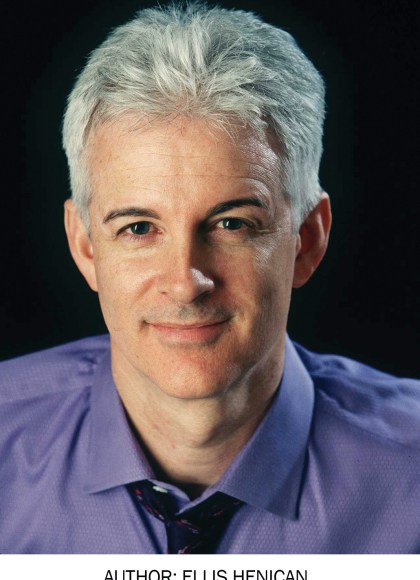

By Ellis Henican

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 8, 2018

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316314435

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 8, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

As timely as it is heartwarming, Tuesday’s Promise is an inspiring memoir of love, service, teamwork, and the remarkable bond between humans and canines.

Following the success of his New York Times bestseller, Until Tuesday, Iraq War veteran Luis Carlos Montalvan advocated for America’s wounded warriors and the healing powers of service dogs.

In this spectacular memoir, Luis and Tuesday brought their healing mission to the next level, showing how these beautifully trained animals could assist soldiers, veterans, and many others with mental and physical disabilities. They rescued a forgotten Tuskegee airman, battled obstinate VA bureaucrats, and provided solace to war heroes coast-to-coast.

As Luis and Tuesday celebrated exhilarating victories, a grave obstacle threatened their work. Luis made great progress battling his own PTSD, but his physical wounds got so bad that he began using a wheelchair. He needed to decide whether to amputate his leg and carry on with a bionic prosthesis. Even as he struggled with dramatic emotional and physical changes, ten-year-old Tuesday was lovingly by his side through it all.

Luis’ death in December 2016 was another terrible tragedy of the invisible wounds of war. This book was his last letter of love to his best friend, Tuesday, and to veterans, readers, friends, and fellow dog lovers everywhere.

-

"Compelling and ultimately heartbreaking...Montalván's ability, with cowriter Henican, to present the ongoing personal and bureaucratic struggles suffered by so many will likely inspire readers to become more engaged with the veterans community. Tuesday's Promise and Montalván's death are reminders of how much America still owes those who have served our country so faithfully. This powerful story has now become simply, and tragically, unforgettable."Booklist (starred review)

-

"Tuesday's Promise is a honorable and worthy tribute to Luis Montalván and Tuesday, the service dog he loved and depended on after bravely serving his country in war. I've seen through my support for Companions for Heroes how a dog can help heal a broken life, serving as a companion with a love that is almost indescribable. Tuesday's Promise captures that relationship better than any book written to date."Dana Perino, former White House Press Secretary and co-host of Fox News' The Five

-

"War affects warriors in a thousand different ways. As Luis discovered so vividly, the battle back home can be the toughest one. With loyal Tuesday at his side, Luis teaches his fellow warriors the true meaning of friendship, support, struggle and love. We all need special allies, human and canine. You can't help but love this pair. American veterans owe them both a huge debt of gratitude."Rorke Denver, formertrainer commander, U.S. Navy SEALs, New York Times bestselling author of DamnFew and Worth Dying For

-

"For those of us who have witnessed the unbiased cold hand of death upon friend, civilian and foe; these ghosts of war follow us home. Every now and then you find someone who understands. Luis and Tuesday stood together fighting against this enemy. Take a moment to understand this plague called PTSD and read Tuesday's Promise. It is a powerful book; the truths that Luis writes so eloquently about will inspire overwhelming pride and profound sadness and hopefully for a moment, allow you to see these apparitions, these ghosts of war."Lt. Jason Redman, retired USNavy, author of The Trident andFounder of SOF Spoken

-

"Luis Montalván brilliantly captures the experience of warriors returning home. This book was an honor and privilege for me to read! I am humbled by the service of these two selfless warriors."Richard R. Peters, retired USNavy SEAL, author of Man of War

-

PRAISE FOR UNTIL TUESDAYVicki Myron, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Dewey

"This story of an incredible service dog is both touching and warm. Some of the struggles are painful to read, because they are so real, but that only makes the triumphs more uplifting. In the course of these pages, Tuesday truly becomes a hero, as does Luis Montalván. This book feels like more than a joy; it feels necessary." -

"This is a profoundly honest book filled with vital lessons about loss, friendship, war and the loving bonds that can save us in our lowest moments. We are all lucky that Capt. Montalván and his dog Tuesday found each other, for in their story we see the possibilities in our own lives."Jeffrey Zaslow, coauthor of the #1 New York Times bestselling The Last Lecture

-

"Wow, what a book! I think I was crying on page 3. The collision of man and dog, and the unbreakable bond they form, made my heart leap. Everyone should read this book to better understand not only the ravages of war, but the amazing capacity of the human spirit to rebound. I dare anyone to read this book and not believe in the power of love to heal."Lee Woodruff, author of In an Instant (with Bob Woodruff) and Perfectly Imperfect

-

"Luis and Tuesday are two true American heroes. This powerful story is a testament to the courage of veterans both on and off the battlefield. Luis is a critical voice for our community, reminding every single veteran that they are not alone."Paul Rieckhoff, Executive Director and Founder, Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America (IAVA) and author of Chasing Ghosts

-

"Until Tuesday explores the unique bond that can occur between dogs and people that ennobles both. This book is a moving tribute to the courage and perseverance of a man as well as the love and the devotion of a remarkable and unforgettable dog."Larry Levin, New York Times bestselling author of Oogy: The Dog Only a Family Could Love

-

"A clarion call to all who profess to care about our veterans and an intense reminder of just how high a price they have already paid, Montalván's mixture of memoir, military history, and pet story results in an urgently important tale."Booklist

-

"A deeply moving story of service, sacrifice, and restoration. Years from now when critics assemble the canon of Iraq War literature, look for Until Tuesday to make everyone's short list."Andrew J. Bacevich, author of Washington Rules: America's Path to Permanent War

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use