By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

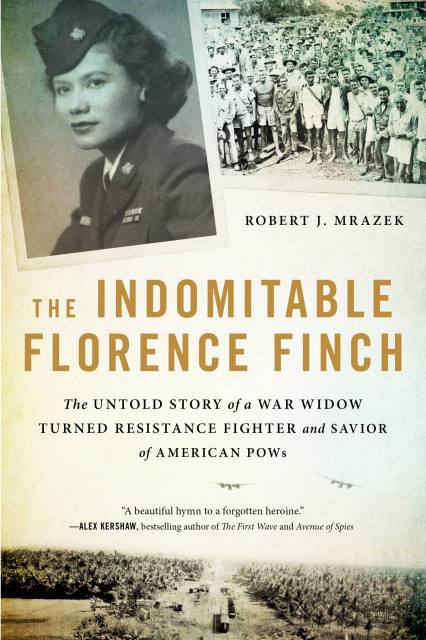

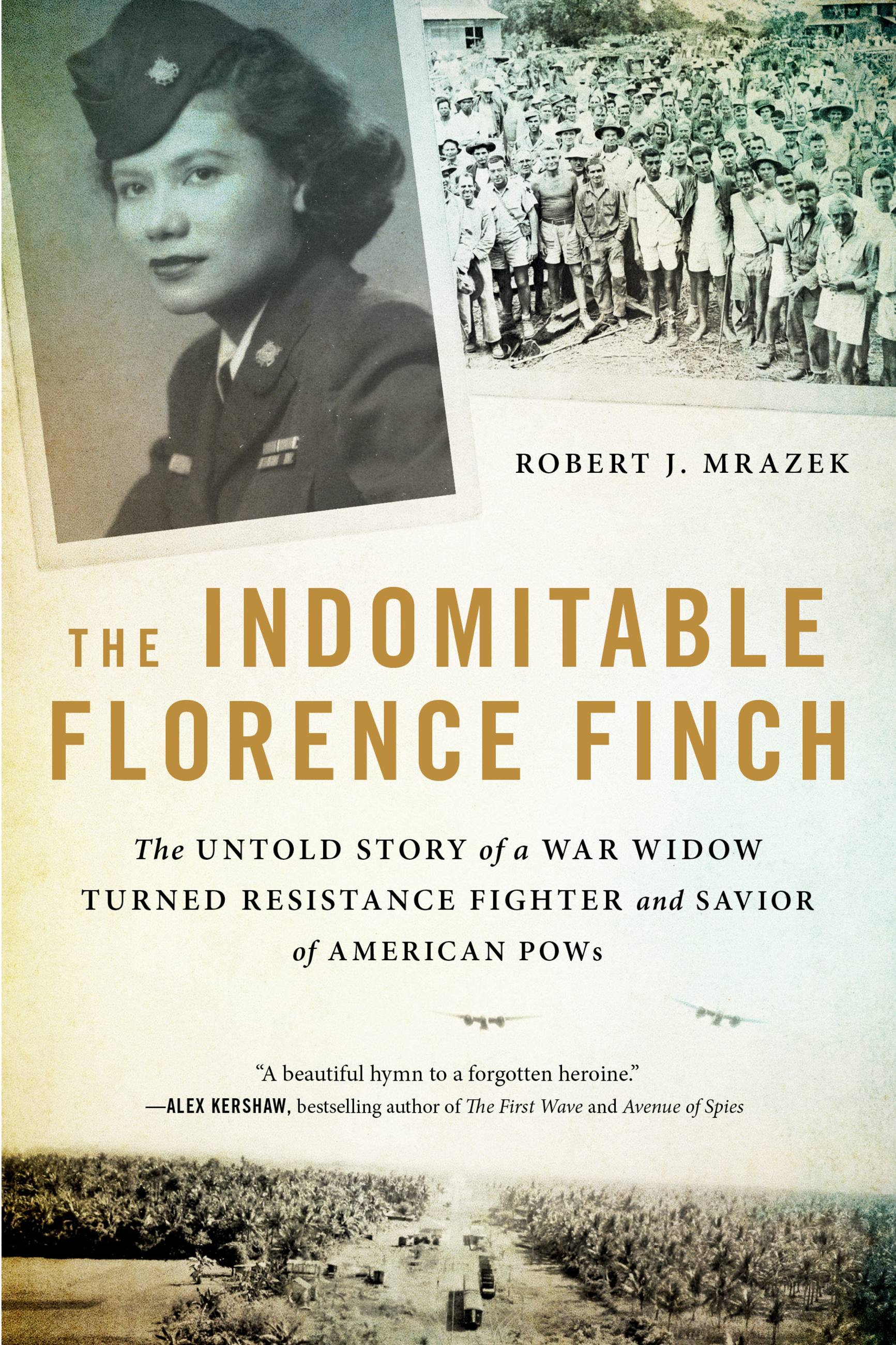

The Indomitable Florence Finch

The Untold Story of a War Widow Turned Resistance Fighter and Savior of American POWs

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 21, 2022

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316422239

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 21, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“An American hero…finally gets her due in this riveting narrative. You will absolutely love Florence Finch: her grit, her compassion, her fight. This isn’t just history; she is a woman for our times.” –KEITH O’BRIEN, the New York Times bestselling author of Fly Girls

The riveting story of an unsung World War II hero who saved countless American lives in the Philippines.

When Florence Finch died at the age of 101, few of her Ithaca, NY neighbors knew that this unassuming Filipina native was a Presidential Medal of Freedom recipient, whose courage and sacrifice were unsurpassed in the Pacific War against Japan. Long accustomed to keeping her secrets close in service of the Allies, she waited fifty years to reveal the story of those dramatic and harrowing days to her own children.

Florence was an unlikely warrior. She relied on her own intelligence and fortitude to survive on her own from the age of seven, facing bigotry as a mixed-race mestiza with the dual heritage of her American serviceman father and Filipina mother.

As the war drew ever closer to the Philippines, Florence fell in love with a dashing American naval intelligence agent, Charles “Bing” Smith. In the wake of Bing’s sudden death in battle, Florence transformed from a mild-mannered young wife into a fervent resistance fighter. She conceived a bold plan to divert tons of precious fuel from the Japanese army, which was then sold on the black market to provide desperately needed medicine and food for hundreds of American POWs. In constant peril of arrest and execution, Florence fought to save others, even as the Japanese police closed in.

With a wealth of original sources including taped interviews, personal journals, and unpublished memoirs, The Indomitable Florence Finch unfolds against the Bataan Death March, the fall of Corregidor, and the daily struggle to survive a brutal occupying force. Award-winning military historian and former Congressman Robert J. Mrazek brings to light this long-hidden American patriot. The Indomitable Florence Finch is the story of the transcendent bravery of a woman who belongs in America’s pantheon of war heroes.

The riveting story of an unsung World War II hero who saved countless American lives in the Philippines.

When Florence Finch died at the age of 101, few of her Ithaca, NY neighbors knew that this unassuming Filipina native was a Presidential Medal of Freedom recipient, whose courage and sacrifice were unsurpassed in the Pacific War against Japan. Long accustomed to keeping her secrets close in service of the Allies, she waited fifty years to reveal the story of those dramatic and harrowing days to her own children.

Florence was an unlikely warrior. She relied on her own intelligence and fortitude to survive on her own from the age of seven, facing bigotry as a mixed-race mestiza with the dual heritage of her American serviceman father and Filipina mother.

As the war drew ever closer to the Philippines, Florence fell in love with a dashing American naval intelligence agent, Charles “Bing” Smith. In the wake of Bing’s sudden death in battle, Florence transformed from a mild-mannered young wife into a fervent resistance fighter. She conceived a bold plan to divert tons of precious fuel from the Japanese army, which was then sold on the black market to provide desperately needed medicine and food for hundreds of American POWs. In constant peril of arrest and execution, Florence fought to save others, even as the Japanese police closed in.

With a wealth of original sources including taped interviews, personal journals, and unpublished memoirs, The Indomitable Florence Finch unfolds against the Bataan Death March, the fall of Corregidor, and the daily struggle to survive a brutal occupying force. Award-winning military historian and former Congressman Robert J. Mrazek brings to light this long-hidden American patriot. The Indomitable Florence Finch is the story of the transcendent bravery of a woman who belongs in America’s pantheon of war heroes.

-

One of BookBub's 12 Best New Nonfiction Books This Summer!One of Amazon's Best Books of July 2020!

-

"A riveting story of courage and sacrifice....Mrazek's book is a treasure, an eminently readable tribute to the wartime heroism of one brave woman."The New York Times Book Review

-

"Robert J. Mrazek unfolds [Florence's] audacious plan to help prisoners and underground freedom fighters....The writing is brisk and energetic; the saga unfolds with enormous suspense."The Wall Street Journal

-

"A monumental biography....Details of Finch's life are blended deftly with the chronology of the Philippines and the world at large....What is special about this biography is the fashion in which certain interesting and controversial topics come into view... historians have long debated whether or not America was really prepared for World War II....Robert Mrazek is to be praised for his serious research and superior writing style, both of which make this chronicle of Florence's real-life adventures an absorbing saga. Her receipt of the Medal of Freedom spotlighted her brave, fearless war effort, just as The Indomitable Florence Finch brings her life and service to our attention."Washington Independent Review of Books

-

"This soul-stirring story of a true heroine of World War II brought tears to my eyes."James M. McPherson, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Battle Cry of Freedom

-

"'Indomitable' is an understatement. Florence's breathtaking story causes us to remember that one person, can indeed, change the lives of many."Judith L. Pearson, award-winning author of Belly of the Beast and Wolves at the Door

-

"A wonderfully graphic and moving account of the selfless and courageous role played during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines by Florence Finch, one of the great unrecognized heroines of World War Two."Saul David, author of Crucible of Hell: The Heroism and Tragedy of Okinawa, 1945 and The Force: The Legendary Special Ops Unit and WWII's Mission Impossible

-

"The searing tragedy and epic heroism of Florence Finch... is an enthralling and inspiring narrative.... A stellar hero of the Philippine resistance who risked all to save the lives of many others."Richard B. Frank, author of MacArthur and winner of the Truman Book Award

-

"An incredibly moving and powerful story. In these absorbing pages, the Filipino experience in World War II comes to life.... Mrazek shows us the triumph of the human spirit over the worst of adversity. Florence Finch is a hero for the ages."John C. McManus, PhD, Curators' Distinguished Professor, Missouri S&T, author of Fire and Fortitude: The U.S. Army in the Pacific War

-

"Thanks to Robert Mrazek's rich and fast-paced narrative, we can add Florence Finch's name to the honor roll of World War II heroes such as Raoul Wallenberg and Oskar Schindler who risked their lives to save others from certain death. Her thrilling story, expertly told by Mrazek, proves that there are still stories of Second World War heroism that remain untold."Thurston Clarke, author of Pearl Harbor Ghosts and the New York Times bestselling The Last Campaign

-

"Robert Mrazek...tells inspiring stories of extraordinary heroism with verve and heart. The story of the amazing war widow, Florence Finch, who risked her life to save American POWs in the Pacific, is by far his finest yet. A beautiful hymn to a forgotten heroine."Alex Kershaw, bestselling author of The First Wave and Avenue of Spies

-

"The story of Florence Finch may not be well-known among WWII history buffs, but it should be, especially after reading Mrazek's meticulous retelling of her life's story...Mrazek... does not leave any important detail out of the book. This biography is thorough, engaging and at times heart-breaking. The narrative seems like it's pulled from a war movie or a spy thriller....The Indomitable Florence Finch restores this powerful woman's story into the public consciousness and gives her life its proper due."John Soltes, Hollywood Soapbox

-

"Mrazek's book provides readers with a firsthand account of the importance of alliances....Readers also get a strong sense of the courage and fortitude demonstrated by both U.S. soldiers and Filipino civilians....Mrazek documents the selfless courage of a civilian woman (and eventual Coast Guard female reservist) who served so others might live."Commander Brooke Millard, U.S. Coast Guard, Proceedings magazine

-

"An American hero-long forgotten-finally gets her due in this riveting narrative. You will absolutely love Florence Finch: her grit, her compassion, her fight. This isn't just history; she is a woman for our times."Keith O'Brien, the New York Times bestselling author of Fly Girls

-

“Riveting…Florence’s astonishing journey is expertly told….This aptly titled book is an un-put-downable story of bravery in a world turned upside down by war….Mrazek, an engaging writer whose work is based on a foundation of extensive research, is at his best in describing Florence’s transformation from being nearly overwhelmed by her circumstances to becoming a savior for so many POWs.”The Portland Press-Herald

-

"Intriguing."Newsday

-

"Mrazek's writing is intelligent...a beautiful story...a book written from the heart."LitHub

-

"Mrazek expertly...showcases a wealth of primary-source material, and skillfully invites readers into Florence's remarkable life. An engaging read for all interested in women's or 20th-century history."Library Journal (starred review)

-

"The richly detailed account of a courageous woman's life."Kirkus Reviews

-

"A crisp chronicle....WWII buffs will relish this inside look at life under Japanese occupation."Publishers Weekly

-

"Acclaimed novelist and historian Mrazek has crafted a compelling narrative which also provides rich coverage of the overall war in the Philippines. A perfect match of author and subject."Booklist

-

"[A] MUST READ for all!... incredibly hard to put down."The Reading Frenzy

-

“Mrazek’s narrative vignettes [are] interesting and informative….If one looks at the whole of [Florence’s] life of early suffering and stigma, quiet service and loyalty and a stunning leap in adverse circumstances to dangerous and life-threatening action for others, it stands to reason that she was what she was for the life she had lived.”The Manila Times

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use