By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

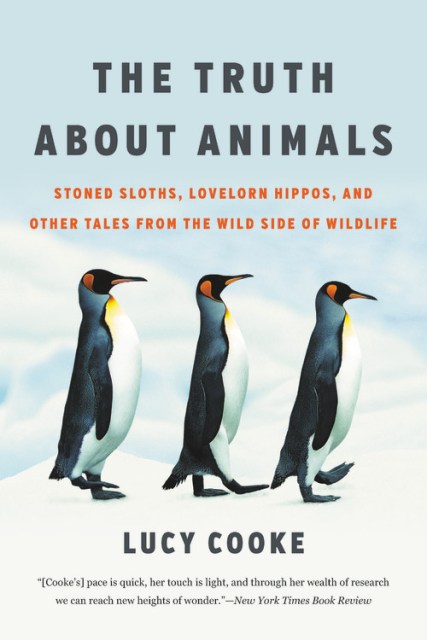

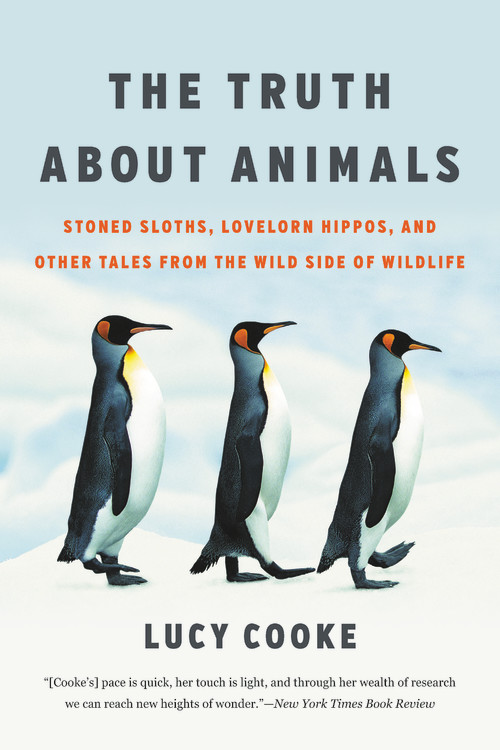

The Truth About Animals

Stoned Sloths, Lovelorn Hippos, and Other Tales from the Wild Side of Wildlife

Contributors

By Lucy Cooke

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 30, 2019

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541674080

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 30, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Humans have gone to the Moon and discovered the Higgs boson, but when it comes to understanding animals, we’ve still got a long way to go. Whether we’re seeing a viral video of romping baby pandas or a picture of penguins “holding hands,” it’s hard for us not to project our own values — innocence, fidelity, temperance, hard work — onto animals. So you’ve probably never considered if moose get drunk, penguins cheat on their mates, or worker ants lay about. They do — and that’s just for starters. In The Truth About Animals, Lucy Cooke takes us on a worldwide journey to meet everyone from a Colombian hippo castrator to a Chinese panda porn peddler, all to lay bare the secret — and often hilarious — habits of the animal kingdom. Charming and at times downright weird, this modern bestiary is perfect for anyone who has ever suspected that virtue might be unnatural.

Genre:

-

On the New York Times Book Review's Paperback Row

-

One of the New York Times Book Review's "17 Refreshing Books to Read This Summer"

-

"Her pace is quick, her touch is light, and through her wealth of research we can reach new heights of wonder."New York Times Book Review

-

"Funny and fascinating, this book will change the way you see wildlife."Bustle

-

"A surefire summer winner...even Cooke's simple facts are funny."New York Times Book Review

-

"Endlessly fascinating."Bill Bryson, author of A Walk in the Woods, A Short History of Nearly Everything, and In a Sunburned Country

-

"Lucy Cooke's modern bestiary is as well-informed as you'd expect from an Oxford zoologist. It's also downright funny."Richard Dawkins, author of The God Delusion, The Selfish Gene, and The Ancestor's Tale, and emeritus fellow of New College, Oxford

-

"Cooke, founder of the Sloth Appreciation Society, raises the profile of many poorly understood animals, revealing surprising, and often hilarious, truths that are much better than the fictions."Scientific American

-

"[A] deeply researched, sassily written history of 'the biggest misconceptions, mistakes and myths we've concocted about the animal kingdom,' spread by figures from Aristotle to Walt Disney."Nature

-

"Cooke's extensive travels, research and delightful sense of humor make The Truth about Animals a fascinating modern bestiary."Seattle Times

-

"In the end, the history of zoology reveals as much about our human foibles as about the animals we study. And this book will leave readers more enlightened about both."Science News

-

"Lucy Cooke's new book makes Playboy seem as tedious and tame as a phone book...In her delightful reading of natural history, [Cooke] is both scientist and standup comic...Trained as an academic, Cooke's writing style is anything but--rather, it's bawdy, irreverent, guiltless, sometimes locker-room-ish and comedic. She makes you feel she's having fun as she pounds out the words...The Truth About Animals is a great read and fascinating fun."Winnipeg Free Press

-

"Lucy Cooke takes equal delight in natural oddities and in people's long struggles to understand them. Part history, part biology, and wholly entertaining, The Truth About Animals is a quirky and edifying romp."Thor Hanson, author of Buzz, Feathers, and The Triumph of Seeds

-

"[An] intriguing and amusing survey of some unusual facets of animal behavior...Cooke puts scientific errors, some of them hilarious, into historical context."Booklist

-

"[A] lighthearted but scientifically rigorous exploration...A pleasure for the budding naturalist in the family--or fans of Gerald Durrell and other animals."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Readers keen on animals and natural history in general should find Cooke's discussion fascinating and educational."Publishers Weekly

-

"Lucy Cooke's [The Truth About Animals] was a joy from beginning to end. Who could resist a writer who argues that penguins have been pulling the wool over our eyes for years, and that, far from being cute and gregarious, they are actually pathologically unpleasant necrophiliacs?"The Guardian (UK)

-

"Each of Cooke's thirteen breezy yet fact-stuffed chapters traces the origins of a long-standing myth about a species or class of animal."Times Literary Supplement (UK)

-

"The eclectic stories come thick and fast, with an equally varied human cast dedicated to uncovering the truth, scientifically or otherwise. Cooke illuminates and mickey-takes in equal measure, and the truth as she tells it is not only unexpected but often bizarre, bawdy and very, very funny. "BBC Wildlife (UK)

-

"As surprising as it is diverse. Consummate natural history writing: illuminating, remarkable - and very, very funny."Alice Roberts, author of The Complete Human Body and The Incredible Unlikeliness of Being

-

"The rising star of natural history ... is she the new David Attenborough?"The Times (UK)

-

"TOP AUTUMN BOOK PICKS: Lucy Cooke's fascinating book is full of mind-boggling stuff. Cooke takes much pleasure in throwing in all manner of amazing facts."Reader's Digest (UK)

-

"A riot of facts....Cooke scores a series of goals with style and panache."The Times (UK)

-

"Beautifully written, meticulously researched, with the science often couched in outrageous asides, this is a splendid read. In fact, I cannot remember when I last enjoyed a non-fiction work so much."Daily Express (UK)

-

"Lucy Cooke unravels myths that will make you laugh out loud. Her knowledge of all things, furry, slimy and scaly is jaw-dropping."The Sun (UK)

-

"BOOK OF THE WEEK: Highly amusing and enlightening new book [from] brilliant zoologist Lucy Cooke."The Idler (UK)

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use