By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

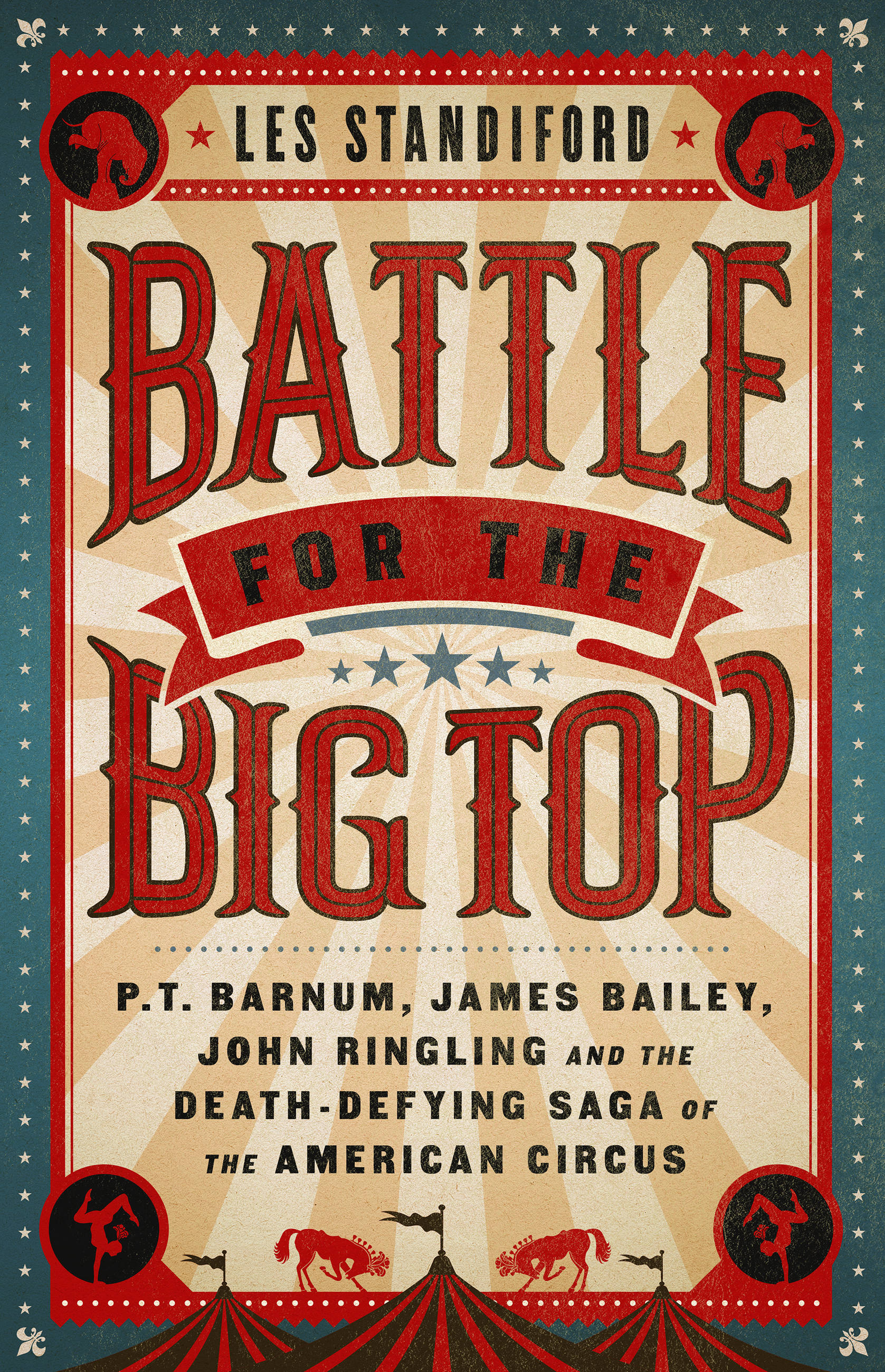

Battle for the Big Top

P.T. Barnum, James Bailey, John Ringling, and the Death-Defying Saga of the American Circus

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 15, 2021

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541762268

Price

$15.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $15.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 15, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Millions have sat under the “big top,” watching as trapeze artists glide and clowns entertain, but few know the captivating stories behind the men whose creativity, ingenuity, and determination created one of our country’s most beloved pastimes.

In Battle for the Big Top, New York Times–bestselling author Les Standiford brings to life a remarkable era when three circus kings—James Bailey, P. T. Barnum, and John Ringling—all vied for control of the vastly profitable and influential American Circus. Ultimately, the rivalry of these three men resulted in the creation of an institution that would surpass all intentions and, for 147 years, hold a nation spellbound.

Filled with details of their ever-evolving showmanship, business acumen, and personal magnetism, this Ragtime-like narrative will delight and enchant circus-lovers and anyone fascinated by the American experience.

-

“Exercising his eye for exotic detail, Les Standiford gives us the charming and captivating saga of the outsized characters who dreamed, connived, and maneuvered to bring Gilded-Age America its most compelling source of entertainment—the circus. What a surprise to learn that behind all those bejeweled elephants and hair-raising acts lay a cutthroat battle to create the Greatest Show on Earth.”Erik Larson, author of The Splendid and the Vile

-

“A mesmerizing, larger-than-life tale from brilliant storyteller Les Standiford--P.T. Barnum himself would tell you it's well worth the price of admission. With acrobatic grace and escalating suspense, Standiford documents the evolution of the American circus, in a masterful work of nonfiction as spell-binding as the monsters, mermaids, balletic elephants and charismatic ringleaders that fill its pages.”Karen Russell, author of the New York Times bestseller Swamplandia!

-

“Battle for the Big Top is as rollicking, infectious, and enthralling as the subject it covers. With verve and style to spare, Les Standiford spins an unforgettable and addictively readable yarn about the three great showmen of the wildest of all entertainments—the American Circus. What a blast.”Dennis Lehane, author of Mystic River and Shutter Island

-

“An epic work of Americana that gives you a front row seat inside the big top. Les Standiford delves deeply into the history of one of America’s favorite and oldest pastimes, examining the three dynamic men who revolutionized it.”Brad Meltzer, bestselling author of The Lincoln Conspiracy

-

“Les Standiford understands that to know the American soul, one needs to understand the circus. Ambitious, insightful and chock full of exotic lore, Battle for the Big Top goes beyond the ballyhoo and delivers the strange and fascinating history of the Greatest Show on Earth.”Stewart O’Nan, author of The Circus Fire

-

"Les Standiford takes us under the big top and behind the curtain in this richly researched and thoroughly engaging narrative that captures all of the entrepreneurial intrigue and spirit of the American circus. Fascinating and endlessly entertaining, you won't be able to put Battle for the Big Top down."Gilbert King, Pulitzer prizewinning author of Devil in the Grove

-

“A blow-by-blow account of the rivalry among James Bailey, John Ringling, P.T. Barnum, and other players in the American circus world…Fans of the circuses of old, as well as students of popular culture, will enjoy this look back.”Kirkus Reviews

-

“A zippy history of Ringling Bros. Barnum & Bailey Circus… Standiford packs the account with colorful circus lore…Readers will relish this entertaining portrait of a bygone American institution.”Publishers Weekly

-

"An engaging stroll down memory lane for children of all ages."Virginia Gazette

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use