Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

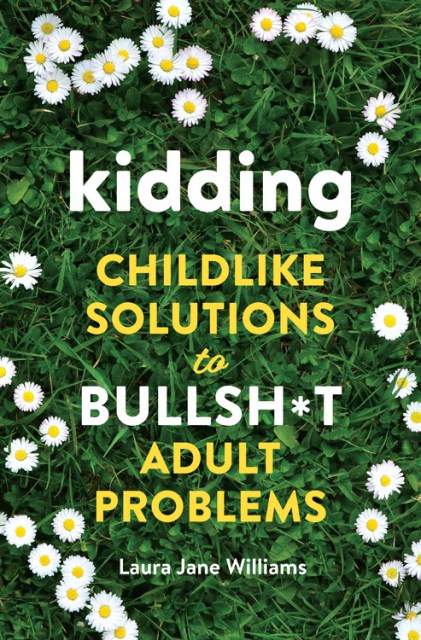

Kidding

Childlike Solutions to Bullsh*t Adult Problems

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.00Price

$22.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $17.00 $22.00 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 9, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Consider this your permission slip to relax, laugh, and finally find happiness. At once hilarious, irreverent, and downright inspiring, Kidding shows you how to connect with your inner child to make your mundane, complicated adult life much simpler (and happier). It’s a book about using your imagination and creativity to find joy, and about being happier by being who you are-which is to say, by being a big kid at heart.

Author Laura Jane Williams argues that you can be an adult but still embrace childlike (not childish) tendencies: you can own your own home and still want to build a pillow fort when the mood strikes; you can pay your bills on time and still snuggle something soft against your face because you’re sad; you can run a business and still take time to play. Divided into 40 short lessons, it’s an accessible, fun introduction to the self-help world that anyone can stomach.

Laura’s experience as a nanny to three young, precocious children has transformed her view on life, and in this book she passes along the lessons she’s learned from them. Because kids live in the present. They lose themselves in what they love, they show off, and they like themselves. Kids are curious by default, and they don’t have limits because they haven’t learned they exist yet. Kids do whatever the f*ck they want, precisely because they want to. To put it simply, kids have the answers, man.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 9, 2018

- Page Count

- 208 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762465736

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use