By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

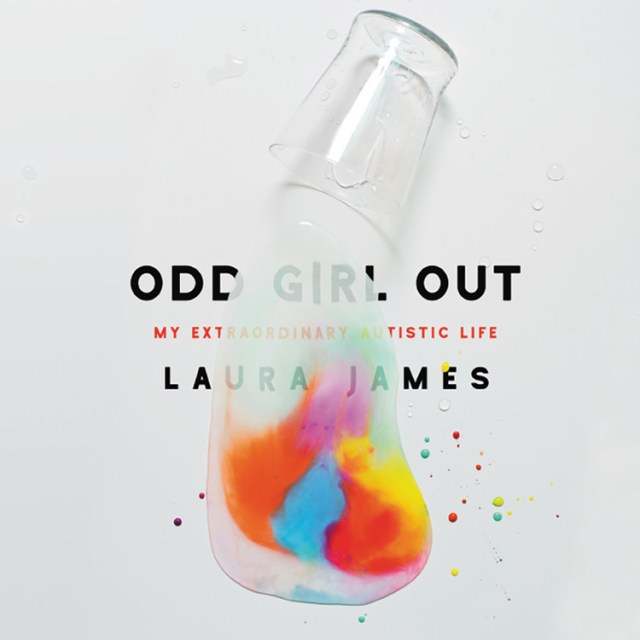

Odd Girl Out

My Extraordinary Autistic Life

Contributors

By Laura James

Read by Lucinda Clare

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 27, 2018

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781549167973

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $17.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 27, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From childhood, Laura James knew she was different. She struggled to cope in a world that often made no sense to her, as though her brain had its own operating system. It wasn’t until she reached her forties that she found out why: Suddenly and surprisingly, she was diagnosed with autism.

With a touching and searing honesty, Laura challenges everything we think we know about what it means to be autistic. Married with four children and a successful journalist, Laura examines the ways in which autism has shaped her career, her approach to motherhood, and her closest relationships. Laura’s upbeat, witty writing offers new insight into the day-to-day struggles of living with autism, as her extreme attention to sensory detail — a common aspect of her autism — is fascinating to observe through her eyes.

As Laura grapples with defining her own identity, she also looks at the unique benefits neurodiversity can bring. Lyrical and lush, Odd Girl Out shows how being different doesn’t mean being less, and proves that it is never too late for any of us to find our rightful place in the world.

-

"Profound and essential. Laura James generously allows us to envison the world through her eyes, as the mundane is infused with a synesthetic beauty. A testament to the aspects of autism that are so rarely appreciated."

--John Elder Robison, author of the New York Times bestseller Look Me in the Eye

-

"Too often a woman's success is pegged to the 'posse' with whom she surrounds herself. Laura James, relying on her independent spirit and the differences that set her apart, becomes an accomplished writer and starts a communications agency while raising four children. Odd Girl Out offers a choice of freedom over conformity through the understanding and embracing of one's disabilities."

--Eileen Cronin, author of Mermaid: A Memoir of Resilience

-

"A masterpiece about autism and a vivid narrative about human frailty and strength."

--Liane Holliday Willey, author of Pretending to be Normal: Living with Asperger's Syndrome and Asperger Syndrome Safety Skills for Asperger Women: How to Save a Perfectly Good Female Life

-

"There are so many myths about what it means to be autistic and Laura tells her story beautifully and truthfully. You will live every moment with her, feel her pain and want to right the wrongs. Some books make a big difference, this is one of them. It should be read by everyone."

--Natasha Harding, The Sun -

"An important, touching and incredibly honest book with a wry sense of humor, which challenges the preconceived ideas people have about autistic life."

--Rachael Lucas, author of Sealed With a Kiss and The State of Grace

-

"Courageous and graceful...Readers will walk away with a new understanding of how autism actually functions."Booklist

-

"Witty and illuminating, James' book offers an intimate look into the mind and heart of an autistic woman who learns to understand her difference not as brokenness but as the thing that makes her unique. A candid and unexpectedly moving memoir of identity and psychological upheaval."Kirkus

-

"Honest and revealing...James demonstrates the complexity of autism, with its strengths as well as weaknesses."Library Journal

-

"James's story, told in an affecting, honest way, is at once intensely personal and extremely relatable... [it] reminds us to have compassion for those who defy our definition of normal, whether or not they have a label."New York Journal of Books

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use