Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

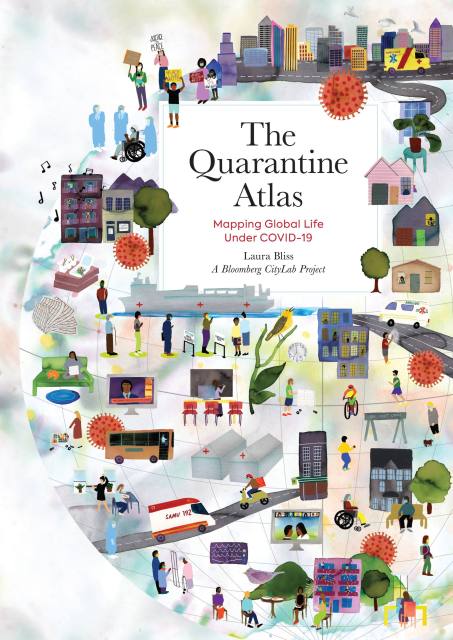

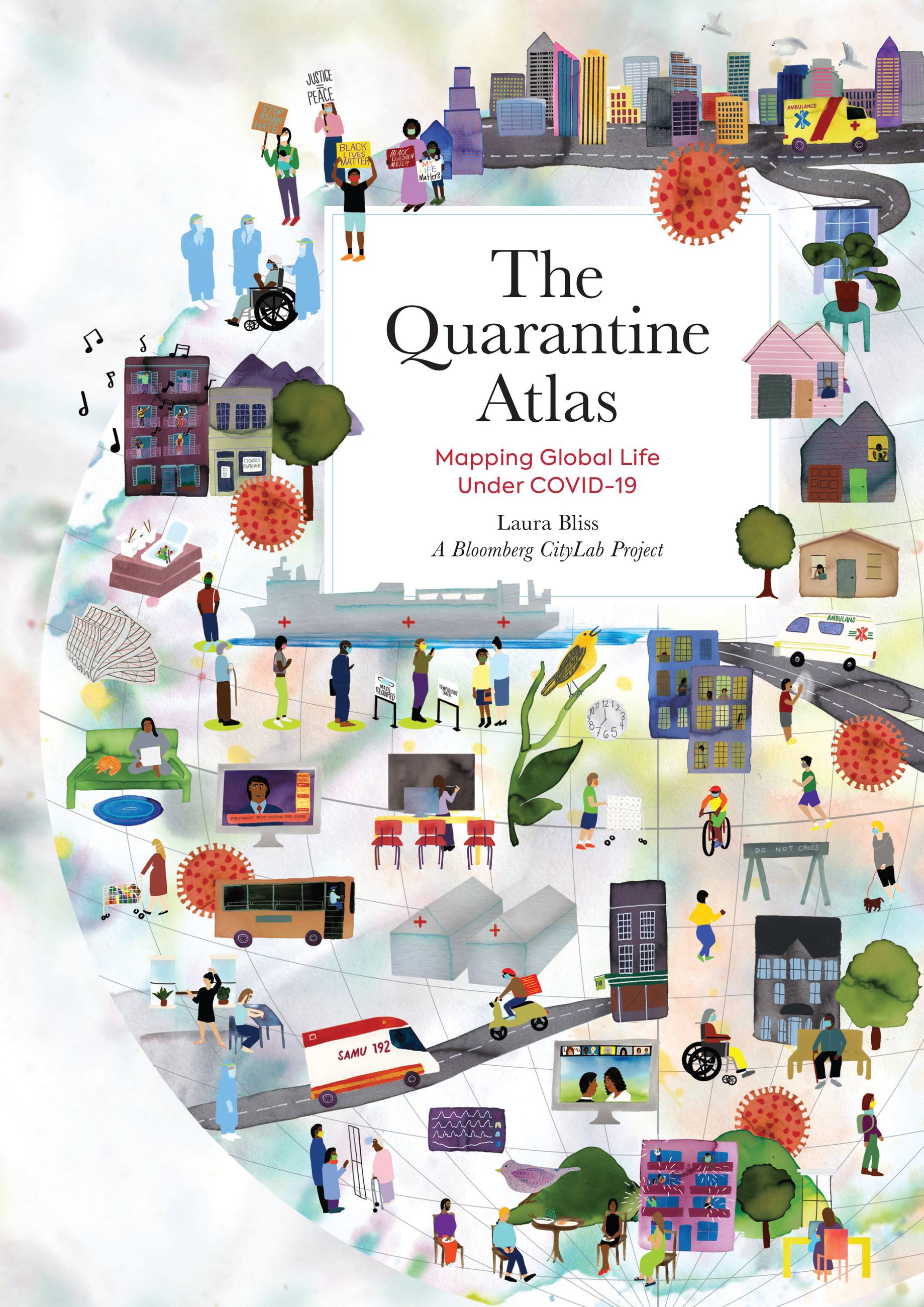

The Quarantine Atlas

Mapping Global Life Under COVID-19

Contributors

By Laura Bliss

By A Bloomberg CityLab Project

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Hardcover $32.00 $40.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 19, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The Quarantine Atlas is a poignant and deeply human collection of more than 65 homemade maps created by people around the globe that reveal how the coronavirus pandemic has transformed our physical and emotional worlds, in ways both universal and unique. Along with eight original essays, it is a vivid celebration of wayfinding through a crisis that irrevocably altered the way we experience our environment.

In April 2020, Bloomberg CityLab journalists Laura Bliss and Jessica Lee Martin asked readers to submit homemade maps of their lives during the coronavirus pandemic. The response was illuminating and inspiring. The 400+ maps and accompanying stories received served as windows into what individuals around the world were experiencing during the crisis and its resonant social consequences. Collectively, these works showed how coronavirus has transformed the places we live, and our relationships to them.

In The Quarantine Atlas, Bliss distills these stunning submissions and pairs them with essays by journalists and authors, as well as notes from the original mapmakers. The result is an enduring visual record of this unprecedented moment in human history. It is also a celebration of the act of mapping and the ways maps can help us connect and heal from our shared experience.

Genre:

-

This gorgeous volume of maps and essays, ‘born of the twilight hours the world spent at once together and apart,’ is at once at a portrait of that time, an excavation of its contours, and an indelible account—often funny, sometimes sad, always revelatory—of how a microbe changed the ways that humans everywhere relate to place. A treasure.Joshua Jelly-Schapiro, co-creator of Nonstop Metropolis and author of Names of New York

-

With vivid, intriguing maps drawn from perspectives both familiar and surprising, The Quarantine Atlas is a fascinating cartographic memoir of how COVID reconfigured the spaces around us. When future historians look back at the geographies of this extraordinary moment, they will almost certainly turn to The Quarantine Atlas as one of the exceptional artifacts of this era. Even if your bookshelves are already full of maps and atlases, this book will offer a provocative and many-voiced reconsideration of how we see ourselves through cartography. It challenges map readers to think about how visual depictions combine fact and feeling, chronicle and argument, partiality and universalism.Garrett Dash Nelson, President & Head Curator, Leventhal Map & Education Center

-

“A visual archive of an unprecedented moment of spatial constraint, and the way we lived those limits in our homes, neighborhoods, and cities…. [These] maps show how people channeled their boredom and grief into bursts of creativity.”Henry Grabar, Slate

- On Sale

- Apr 19, 2022

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780762478132

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use