By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

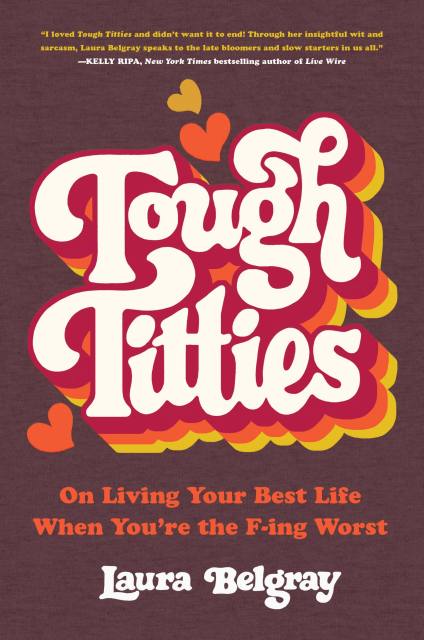

Tough Titties

On Living Your Best Life When You're the F-ing Worst

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 13, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

From award-winning TV writer Laura Belgray, a hilarious collection of full-body-cringe, watch-through-your-fingers life lessons her own husband calls “loser Sex and the City.”

What does it take to grow up cool and popular, master adulthood, fast track your success, and always be your best? Laura Belgray wouldn’t know.

Her wildly relatable coming-of-age stories include hate-following her 6th grade bully on social media decades later; moving home post-college to measure her self-worth in hookups with Upper West Side bartenders; dating a sociopathic man-baby; proving herself in the early ‘90s at New York’s coolest magazine (as the world’s worst intern); falling for get-rich-quick schemes on the Internet; and, most of all, saying “tough titties” to the supposed-to’s in life: driving a car, being on time, handing in your paperwork, learning to roast a chicken, and having kids.

Peppered with cutting insights on our confusing, self-helpy culture that calls hair removal “self care” and tells us to give our 110% but also to give zero f*cks, Tough Titties will leave you feeling better about, well, everything. Let’s face it: we’re all tired of shame-spiraling after being told what to do when we know we’re not going to do any of it.

Tough Titties is one big permission slip to be a dork, a sometimes-unspiritual slacker, a late bloomer and, ultimately, 100% yourself. It’ll also have you snort-laughing in public and tapping whoever’s nearby to say, “Lemme read you one more part!” Which is annoying, but tough titties.

“Nobody makes me laugh like Laura Belgray. She’s got a one-of-a kind knack for taking the shame out of life’s most humiliating moments. Tough Titties is a hilarious, must-read permission slip to be 100% you.” –Marie Forleo, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Everything is Figureoutable

Genre:

-

“I loved Tough Titties and didn’t want it to end! Through her insightful wit and sarcasm, Laura Belgray speaks to the late bloomers and slow starters in us all.”Kelly Ripa, New York Times bestselling author of Live Wire

-

“Nobody makes me laugh like Laura Belgray. She’s got a one-of-a kind knack for taking the shame out of life’s most humiliating moments. Tough Titties is a hilarious, must-read permission slip to be 100% you.”Marie Forleo, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Everything is Figureoutable

-

“Where has Laura Belgray been all my life? Hilarious, eloquent, wise, she writes with delicious honesty about coming of age, falling in love, and finding meaning in these weird and chaotic times. I loved Tough Titties so much I want to press it in the hands of everyone I pass on the street!”Joanna Rakoff, international bestselling author of My Salinger Year and A Fortunate Age

-

“I’ve been a fan of Laura Belgray’s hilarious, tell-it-like-it-is writing for years. She was an early influence on my own craft, and I count her among my teachers. Laura’s for anyone who keeps waking up disappointed to find they didn’t become a different, more pulled-together person in their sleep.”Holly Whitaker, New York Times bestselling author of Quit Like a Woman

-

"If you're worried you're doing life wrong, Tough Titties will give you hope. It's proof that you can be a flaming mess, make questionable choices, have no plan, and turn out just fine. I laughed, I cringed, I nodded in recognition—on just about every page."Emily McDowell, founder of Em & Friends

-

"Laura Belgray's voice is smart, shockingly honest, and laugh-out-loud funny. In these essays, you'll find that best friend who always makes you feel better, about everything."Kimberly McCreight, New York Times bestselling author of Reconstructing Amelia and A Good Marriage

- On Sale

- Jun 13, 2023

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780306826047

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use