By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

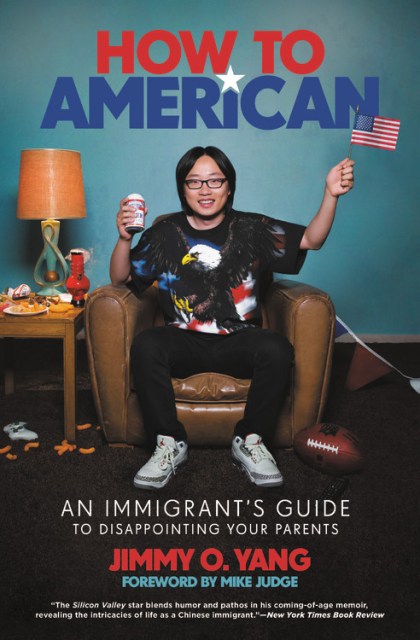

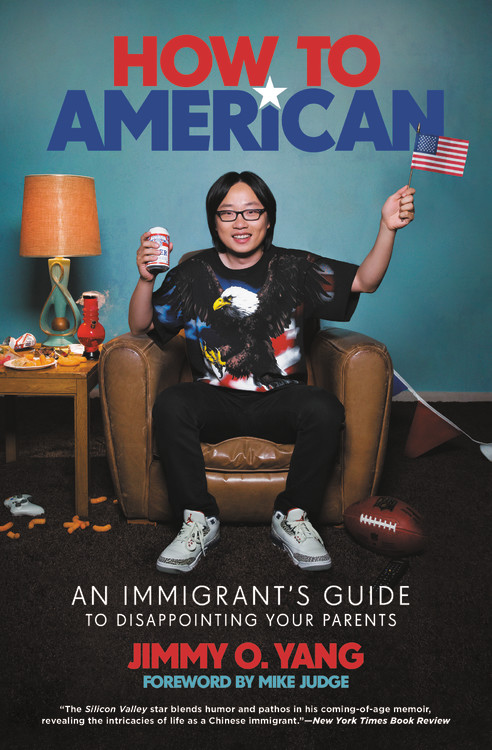

How to American

An Immigrant's Guide to Disappointing Your Parents

Contributors

Foreword by Mike Judge

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 14, 2020

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306903519

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Hardcover $35.00 $45.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.98

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 14, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“I turned down a job in finance to pursue a career in stand-up comedy. My dad thought I was crazy. But I figured it was better to disappoint my parents for a few years than to disappoint myself for the rest of my life. I had to disappoint them in order to pursue what I loved. That was the only way to have my Chinese turnip cake and eat an American apple pie too.”

Jimmy O. Yang is a standup comedian, film and TV actor and fan favorite as the character Jian Yang from the popular HBO series Silicon Valley. In How to American, he shares his story of growing up as a Chinese immigrant who pursued a Hollywood career against the wishes of his parents: Yang arrived in Los Angeles from Hong Kong at age 13, learned English by watching BET RapCity for three hours a day, and worked as a strip club DJ while pursuing his comedy career. He chronicles a near deportation episode during a college trip Tijuana to finally becoming a proud US citizen ten years later. Featuring those and many other hilarious stories, while sharing some hard-earned lessons, How to American mocks stereotypes while offering tongue in cheek advice on pursuing the American dreams of fame, fortune, and strippers.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use