Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

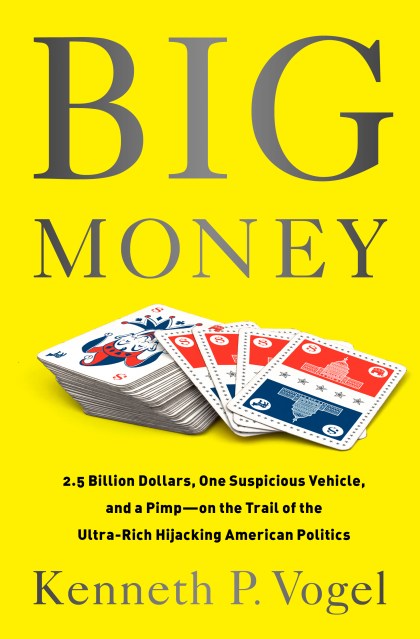

Big Money

2.5 Billion Dollars, One Suspicious Vehicle, and a Pimp-on the Trail of the Ultra-Rich Hijacking American Politics

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 3, 2014

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610393393

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $15.99 $20.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 3, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Big Money is a rollicking tour of a new political world dramatically reordered by ever-larger flows of cash. Ken Vogel has breezed into secret gatherings of big-spending Republicans and Democrats alike — from California poolsides to DC hotel bars — to brilliantly expose the way the mega-money men (and rather fewer women) are dominating the new political landscape.

Great wealth seems to attach itself to outsize characters. From the casino magnate Sheldon Adelson to the bubbling nouveau cowboy Foster Friess; from the Texas trial lawyer couple, Amber and Steve Mostyn, to the micromanaging Hollywood executive Jeffrey Katzenberg — the multimillionaires and billionaires are swaggering up to the tables for the hottest new game in politics. The prize is American democracy, and the players’ checks keep getting bigger.

-

Walter Shapiro, Brennan Center for Justice

“Vogel's paparazzi tactics -- coupled with relentless traditional reporting -- have made Big Money the smartest and most revealing book chronicling the Super PAC era. Instead of predictable legal analysis and a mind-numbing march of statistics, Vogel tries to grasp what motivates the wealthy to invest so heavily in Super PACs. And his answers do not fit into the neat ideological cubbyholes of either campaign reformers or believers in the nonsensical, but powerful, doctrine that money equals free speech.”

Chris Moody, Yahoo! News

“Pull[s] back the curtain on some of the most important players... Through impressive sourcing, Vogel's work...offers a peek into the secretive universe of megadonors in the post-Citizens United era.”

The Economist's Democracy in America blog

“A highly entertaining account of the adventures of billionaires in politics.”

Joel Connelly, SeattlePI.com

“Vogel manages to entertain while reporting on the politics of excess, even when things turn sinister… The most fascinating aspect of Vogel's book is what manner of candidate big money culture produces, with a look back to 2012 and ahead at 2016... Buy Hillary's book for your coffee table, but take 'Big Money' on vacation.” -

Barton Swaim, Wall Street Journal

“With ‘Big Money'—-which takes up the Kochs and other rich political contributors, including Sheldon Adelson, Rob McKay and liberal Texas lawyers Steve and Amber Mostyn—-Mr. Vogel has succeeded in doing what I, for one, didn't think possible. He has made the subject of money in politics entertaining—indeed, gripping. He does this by a combination of factual analysis, eyebrow-raising scoops and zany stories.”

Bethany McLean, Washington Post

“[Vogel] knows the characters and gets the game. Want to understand Mitt Romney's fundraising operation, how Jim Messina mobilized big donors for Obama's 2012 campaign or the war chest that is already growing underneath Hillary Clinton? Vogel tells the stories. He also offers lots of detail on one of the most fascinating frenmities in modern right-wing politics: Karl Rove and the Koch brothers. And he offers great facts to bolster his overall claim...To his great credit, Vogel is also pretty even-handed...This is a book by an insider, for insiders.”