By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

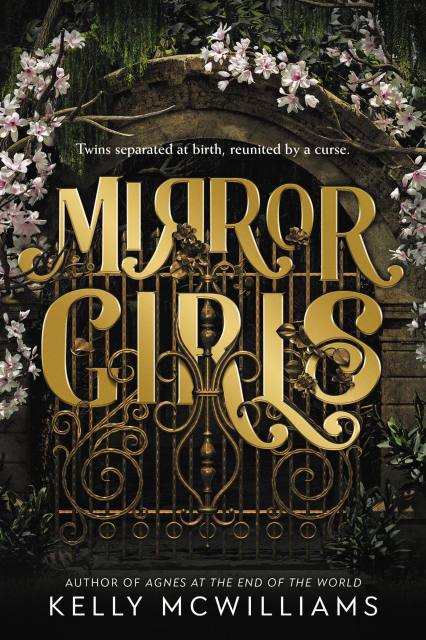

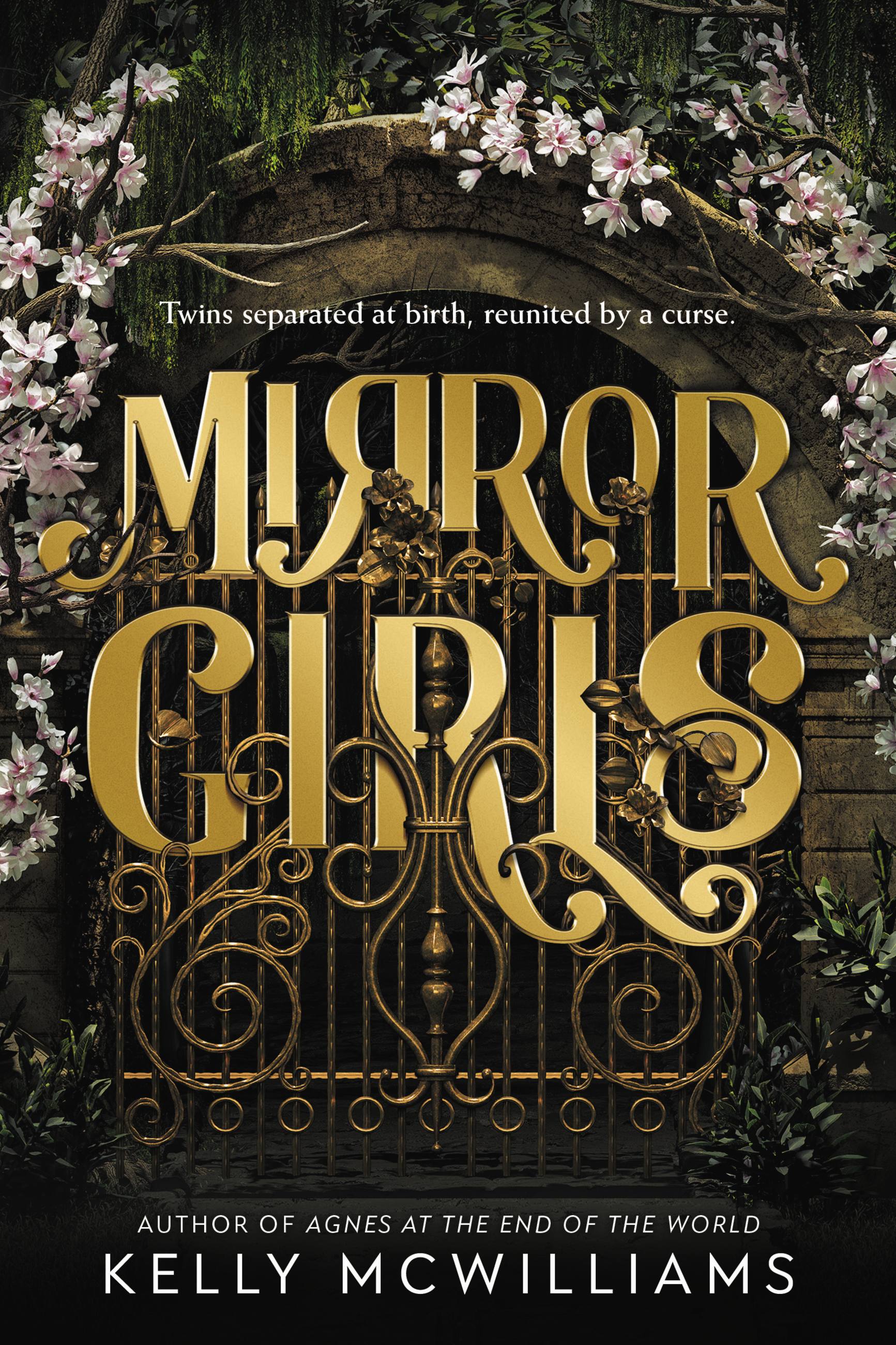

Mirror Girls

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 8, 2022

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780759553859

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Hardcover $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.98

- Trade Paperback $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 8, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A thrilling gothic horror novel about biracial twin sisters separated at birth, perfect for fans of Lovecraft Country and The Vanishing Half

As infants, twin sisters Charlie Yates and Magnolia Heathwood were secretly separated after the brutal lynching of their parents, who died for loving across the color line. Now, at the dawn of the Civil Rights Movement, Charlie is a young Black organizer in Harlem, while white-passing Magnolia is the heiress to a cotton plantation in rural Georgia.

Magnolia knows nothing of her racial heritage, but secrets are hard to keep in a town haunted by the ghosts of its slave-holding past. When Magnolia finally learns the truth, her reflection mysteriously disappears from mirrors—the sign of a terrible curse. Meanwhile, in Harlem, Charlie’s beloved grandmother falls ill. Her final wish is to be buried back home in Georgia—and, unbeknownst to Charlie, to see her long-lost granddaughter, Magnolia Heathwood, one last time. So Charlie travels into the Deep South, confronting the land of her worst nightmares—and Jim Crow segregation.

The sisters reunite as teenagers in the deeply haunted town of Eureka, Georgia, where ghosts linger centuries after their time and dangers lurk behind every mirror. They couldn’t be more different, but they will need each other to put the hauntings of the past to rest, to break the mirrors’ deadly curse—and to discover the meaning of sisterhood in a racially divided land.

-

"Steeped in atmosphere, equals parts ghost and sororal love story, McWilliams has written a pitch-perfect southern gothic thriller about race, family, and what it means to call a place home."Christina Hammonds Reed, award-winning author of The Black Kids

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Praise

-

"Steeped in atmosphere, equals parts ghost and sororal love story, McWilliams has written a pitch-perfect southern gothic thriller about race, family, and what it means to call a place home."Christina Hammonds Reed, award-winning author of The Black Kids