Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

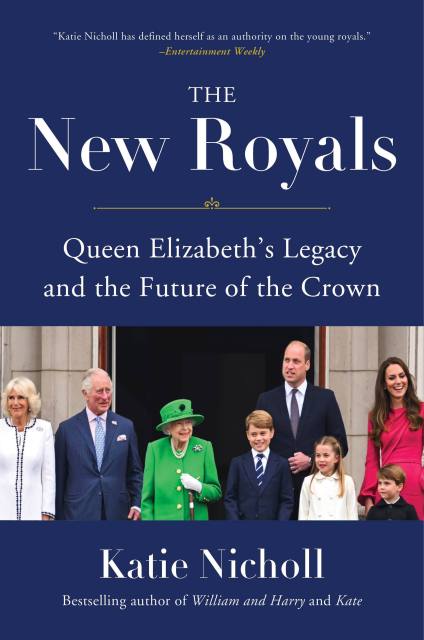

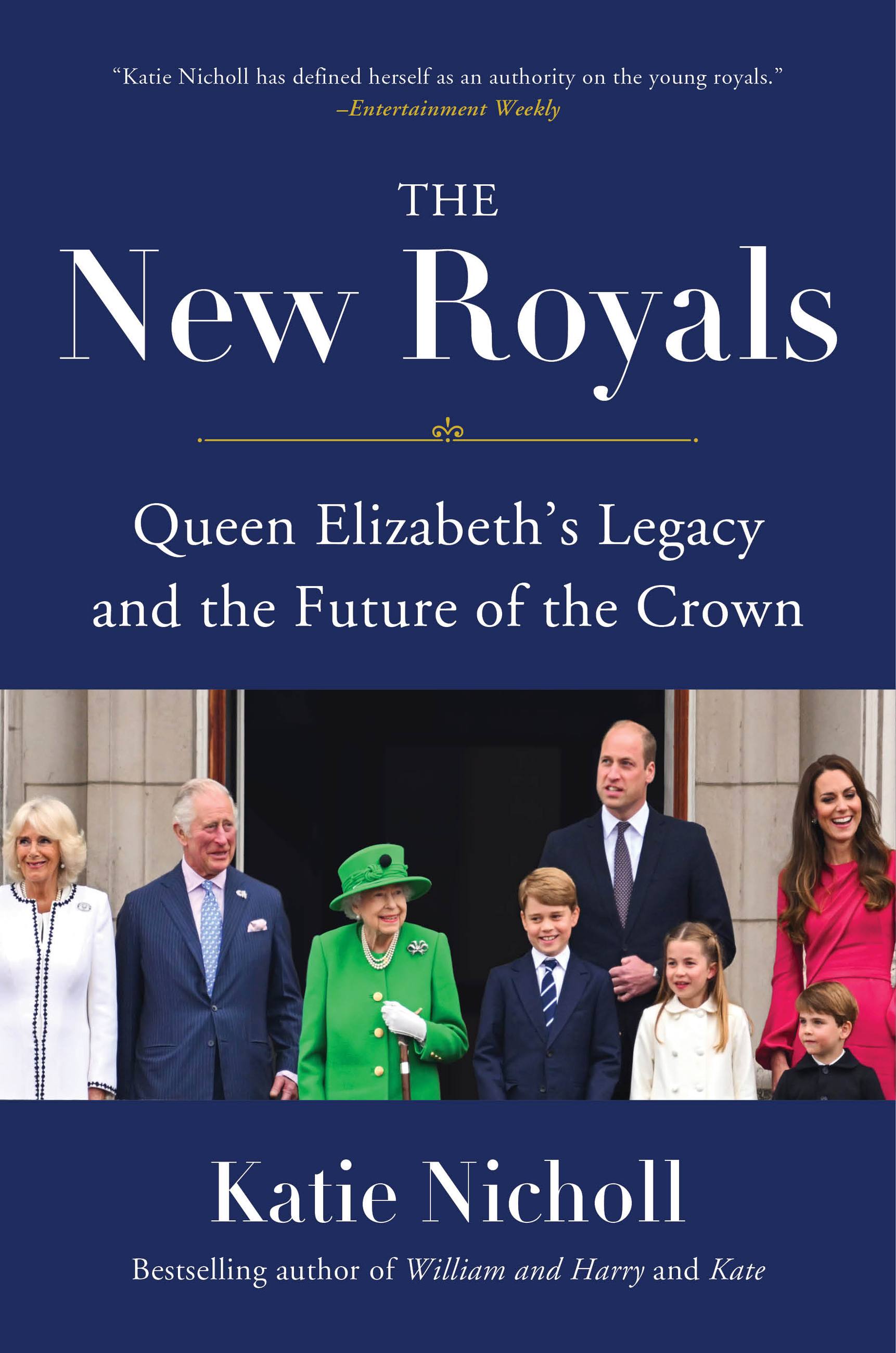

The New Royals

Queen Elizabeth's Legacy and the Future of the Crown

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 4, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Vanity FairRoyals correspondent and bestselling author ofWilliam and HarryandKateexplores the remarkable life and legacy of Queen Elizabeth II, with new chapters to include the last few months of her reign, and the rise of King Charles III.

For seventy years, Queen Elizabeth ruled over an institution and a family. During her lifetime she was constant in her desire to provide a steady presence and to be a trustworthy steward of the British people and the Commonwealth. In the face of her uncle’s abdication, in the uncertainty of the Blitz, and in the tentative exposure of her family and private life to the public via the press, Elizabeth became synonymous with the crown.

But times change. Recent years have brought grief and turmoil to the House of Windsor, and even as England celebrated the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee, there were calls for a changing of the guard.

In The New Royals, journalist Katie Nicholl provides a nuanced look at Elizabeth’s remarkable and unrivalled reign, with new stories from Palace courtiers and aides, documentarians, and family members. She examines King Charles and Queen Consort Camilla’s decades in waiting and beyond—where “The Firm” is headed as William and Kate present the modern faces of an ancient institution. In the wake of Harry and Meghan leaving the Royal Family and Prince Andrew’s spectacular fall from grace, the royal family must reckon with its history, the light and the dark, in order to chart a course for Britain beyond its Queen and to show that it is an institution capable of leadership in an ever-changing modern world.

Genre:

-

"A thoughtful and penetrating look at Queen Elizabeth II and the monarchy going forward by one of the best-connected royal commentators. Katie Nicholl shines an incisive light on the difficulties and opportunities facing the present and future generation of the royal family."Andrew Morton

-

"A unique look back and ahead for the Royal Family....In the book, [Katie Nicholl] paint this very vivid life and legacy of Queen Elizabeth."Al Roker, The TODAY Show

-

“A cracking book! The New Royals is an essential look at what’s next for the crown.”Piers Morgan

-

“Katie Nicholl does tremendous work as Vanity Fair's royals correspondent, whether it's a groundbreaking exclusive or a delicious morsel of palace intel. The New Royals is more of Katie at her best, gathering string on one of the dynamic family sagas of our time.”Claire Howorth, executive editor, Vanity Fair

-

“The New Royals is a fascinating look at how the Royal House of Windsor is preparing for the next 100 years of the dynasty. As ever, Katie Nicholl takes viewers on a journey to the very heart of ‘The Firm’ through meticulous research and compelling interviews with real insiders. It is a must-read for every royal fan.”Nick Bullen, Editor in Chief, True Royalty TV

-

Praise for Katie Nicholl:

-

"An entertaining, richly-photographed book... Nicholl retraces the well-known story of the boys' triumphs and travails... Chattily and fondly, Nicholl chronicles the boys' lives, and gives Kate ample and generous treatment."The New York Times

-

"Through interviews with friends, acquaintances, and confidants, best-selling author and Vanity Fair royals correspondent Katie Nicholl delivers a deep dive into the life of Kensington's most improved prince."Vanity Fair

-

"Katie Nicholl has defined herself as an authority on the young royals.... The book turns to numerous inside sources for swoon-worthy accounts of their love, while also offering an in-depth look at Harry's life overall."Entertainment Weekly

-

"Romance lovers will be happy."USA Today

-

"Nicholl's Harry: Life, Loss, and Love reveals... intimate glimpses into the already highly scrutinized lives of Meghan and Harry."Slate

-

"The new Prince Harry book is hot...a must-read material for royal fans.The Globe and Mail

-

"Katie has become the go-to source on all things royal."KTLA.com

-

"It's guaranteed that this tome will be . . . [eye-opening,] as Nicholl is deeply embedded in the royal scene."The New York Observer

-

"Perfect for those who are fans of the royal family.... A Hollywood biography of a young leading man... for whom something momentous is happening."San Francisco Book Review

-

"[A] crown jewel of a book."Bella Magazine

-

"Using her unrivalled sources [Katie Nicholl] has written the most revealing book ever about Princes William and Harry... the most vivid and engaging study yet of our future King."Mail on Sunday

- On Sale

- Oct 4, 2022

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780306827976

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use