By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

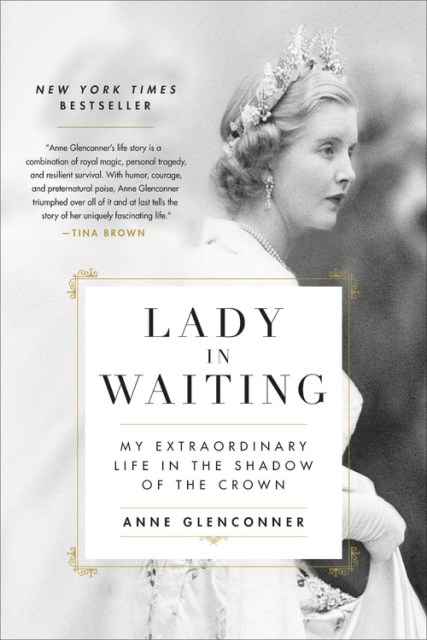

Lady in Waiting

My Extraordinary Life in the Shadow of the Crown

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 16, 2021

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780306846373

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 16, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Discover untold secrets with this extraordinary memoir of drama and tragedy by Anne Glenconner—a close member of the royal circle and lady-in-waiting to Princess Margaret.

Anne Glenconner has been at the center of the royal circle from childhood, when she met and befriended the future Queen Elizabeth II and her sister, the Princess Margaret. Though the firstborn child of the 5th Earl of Leicester, who controlled one of the largest estates in England, as a daughter she was deemed “the greatest disappointment” and unable to inherit. Since then she has needed all her resilience to survive court life with her sense of humor intact.

A unique witness to landmark moments in royal history, Maid of Honor at Queen Elizabeth’s coronation, and a lady in waiting to Princess Margaret until her death in 2002, Anne’s life has encompassed extraordinary drama and tragedy. In Lady in Waiting, she will share many intimate royal stories from her time as Princess Margaret’s closest confidante as well as her own battle for survival: her broken-off first engagement on the basis of her “mad blood”; her 54-year marriage to the volatile, unfaithful Colin Tennant, Lord Glenconner, who left his fortune to a former servant; the death in adulthood of two of her sons; a third son she nursed back from a six-month coma following a horrific motorcycle accident. Through it all, Anne has carried on, traveling the world with the royal family, including visiting the White House, and developing the Caribbean island of Mustique as a safe harbor for the rich and famous-hosting Mick Jagger, David Bowie, Raquel Welch, and many other politicians, aristocrats, and celebrities.

With unprecedented insight into the royal family, Lady in Waiting is a witty, candid, dramatic, at times heart-breaking personal story capturing life in a golden cage for a woman with no inheritance.

New York Times Bestseller

USA Today Bestseller

The Sunday Times Bestseller

The Globe and Mail Bestseller

ABA Indie Bestseller

The Times (UK) Memoir of the Year

One of Newsweek‘s Most Anticipated Books of 2020

Anne Glenconner has been at the center of the royal circle from childhood, when she met and befriended the future Queen Elizabeth II and her sister, the Princess Margaret. Though the firstborn child of the 5th Earl of Leicester, who controlled one of the largest estates in England, as a daughter she was deemed “the greatest disappointment” and unable to inherit. Since then she has needed all her resilience to survive court life with her sense of humor intact.

A unique witness to landmark moments in royal history, Maid of Honor at Queen Elizabeth’s coronation, and a lady in waiting to Princess Margaret until her death in 2002, Anne’s life has encompassed extraordinary drama and tragedy. In Lady in Waiting, she will share many intimate royal stories from her time as Princess Margaret’s closest confidante as well as her own battle for survival: her broken-off first engagement on the basis of her “mad blood”; her 54-year marriage to the volatile, unfaithful Colin Tennant, Lord Glenconner, who left his fortune to a former servant; the death in adulthood of two of her sons; a third son she nursed back from a six-month coma following a horrific motorcycle accident. Through it all, Anne has carried on, traveling the world with the royal family, including visiting the White House, and developing the Caribbean island of Mustique as a safe harbor for the rich and famous-hosting Mick Jagger, David Bowie, Raquel Welch, and many other politicians, aristocrats, and celebrities.

With unprecedented insight into the royal family, Lady in Waiting is a witty, candid, dramatic, at times heart-breaking personal story capturing life in a golden cage for a woman with no inheritance.

New York Times Bestseller

USA Today Bestseller

The Sunday Times Bestseller

The Globe and Mail Bestseller

ABA Indie Bestseller

The Times (UK) Memoir of the Year

One of Newsweek‘s Most Anticipated Books of 2020

-

"Anne Glenconner's life story is a combination of royal magic, personal tragedy and resilient survival. With humor, courage, and preternatural poise, Anne Glenconner triumphed over all of it and at last tells the story of her uniquely fascinating life."Tina Brown

-

"Exceptional."Andre Leon Talley

-

"A remarkable memoir--containing, at last, a genuine portrait of Princess Margaret from one who knew her well. But this book is poignant too, and through the pages shine [Anne's] courage and good-humored acceptance of her demons and tragedies."Hugo Vickers

-

"A smart, dishy, and truly touching autobiography."Town & Country

-

"Stalwart and disarmingly honest....Emotion resonates through this delightful memoir...candid, humorous."The Wall Street Journal

-

"I couldn't put it down. Funny and touching - like looking through a keyhole at a lost world."Rupert Everett

-

"Riveting...[Anne's] stiff upper lip never quivers."Oprah Magazine

-

"This memoir of consorting with Princess Margaret and the royal family is remarkable."The Sunday Times (UK)

-

"A startling, rare, beguiling insight into a lost world of royalty and celebrity with as many tears as there are titles... Anne's story - a breath-taking array of top-drawer gossip--is told with an endearing modesty and with an extraordinary sense of surprise that all these things happened to her... The book is a diamond-mine of glittering asides."Daily Express

-

"Extraordinary."Loose Women

-

"[An] upfront account of her life... [you'll] laugh out loud, exclaim in shock, and cry as [you] read it....An amazing read. There's so much humanity... as well as stories of glitz and glamour and royalty... it's a life fully lived.""Nightlife" ABC radio (AU)

-

"Gentle, wise, unpretentious, but above all inspiring."The Times (UK)

-

"A candid, witty and stylish memoir."Miranda Seymour, Financial Times

-

"Astounding memoir."India Knight

-

"Discretion and honor emerge as the hallmarks of Glenconner's career as a royal servant, culminating in this book which manages to be both candid and kind."The Guardian

-

"It's a total hoot - I can't put it down."Janet Street-Porter, Daily Mail

-

"A romp of an autobiography."The Times (UK)

-

"As her memoir makes clear, her capacity 'to get on with life and not dwell,' even in the most extreme circumstances, is heroic. There is, nevertheless, a vein of quiet anger. The book is a retaliation as much as a reminiscence. It is also a finely drawn double portrait. Margaret is in the foreground, spotlit, while behind her Glenconner's life plays out with such self-effacing matter-of-factness that it takes time for the reader to realise that of these two intertwined biographies Glenconner's is by far the more remarkable....Glenconner has an eye for detail, and if her picture of Princess Margaret dwells on the positives, it makes no attempt to conceal the difficulties....Lady Anne brings out a touchingly naive side of Margaret's character, visible only to an insider familiar with the realities of royal life....Her book is partly a meditation on how much or how little she could have done differently. Although regret isn't in her emotional register, there is an unmistakable sadness when she remembers certain things, especially about her children, and her 'heart sinks.'"London Review of Books

-

"Marvelous book . . . one's eyes were on stalks."Jan Moir, Daily Mail

-

"Lady in Waiting...will make you laugh and cry and gasp....At the heart is loss, grief, stoicism, and love."Airmail

-

"I hooted my way through Anne Glenconner's Lady in Waiting... Glenconner's memoir of three decades as Princess Margaret's chief courtier is matter of fact about her bonkers life, making it all the more amusing"Marcus Field, Evening Standard

-

"A record, funny and sometimes dazzling, of a way of life now almost disappeared."Rachel Cooke, Observer

-

"Rollicking... a fascinating, anthropological portrait of the... privilege-soaked world of the British aristocracy... extraordinary anecdotes... Anne's book paints such a rich picture of the aristocracy it's impossible not to marvel at the institution, both in admiration and horror."Sydney Morning Herald

-

"One of the most enjoyable books of 2019."Alison Pearson, The Sunday Telegraph

-

"Royal obsessives and casual observers alike will devour this memoir by the confidante-a noble herself-of Princess Margaret. Glenconner candidly writes about the unimaginable tragedies she endured in her personal life, and of the gilded affairs she witnessed on the periphery of royal life."Newsweek

-

"It's an astonishing story and narrated with a deceptive simplicity. There isn't a boring sentence in the entire book."Daily Mail

-

"A must-read book of the year."Craig Brown, Mail on Sunday

-

"A page-turner, filled with humor and tragedy."Carleton Varney, Palm Beach Daily News

-

"Meticulously detailed....[W]hat makes this account fresh and poignant is Glenconner's use of affluent characters to demonstrate the extent to which class trumps power....By unflinchingly examining everything from her troubled marriage and her fraught relationship with her children to the solace she found in service, the author emerges as a flawed yet steely woman worthy of respect. In laying her life bare, she demonstrates the limitations of being a woman in the British class system, showing that privilege is no insulation from suffering or pain. A must-have for loyal royal fans."Kirkus Reviews

-

"In this genuine and candid work, Lady Anne recounts her story, offering some rare insight into the uniquely fascinating world of royal life."BookRiot

-

"Whether describing scenes of delicacy or debauchery, these insider accounts are fascinating. Glenconner is unfailingly perceptive, honest, and amazingly down-to-earth, a survivor who embodies the British trait of "getting on with it.""Booklist (starred review)

-

"Lady Glenconner provides an open and honest look into the private lives of England's royal family and the most elite members of society. The author's sense of humor shines through in her writing, bringing levity to some of the difficult times that peppered her life."Library Journal (starred review)

-

"Spectacular....Royal watchers know that Lady Glenconner is a sharp-tongued wit who pulls no punches."Bustle

-

"An affectionate but honest and down-to-earth portrait of time spent with the royals behind palace doors."Amazon Book Review

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use