By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

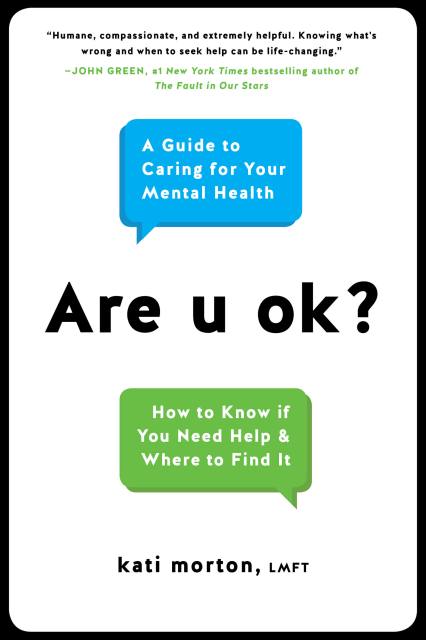

Are u ok?

A Guide to Caring for Your Mental Health

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 11, 2018

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Balance

- ISBN-13

- 9780738234984

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $24.00 $30.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.98

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 11, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Learn hands-on coping strategies for managing anxiety, depression, eating disorders, and other mental health concerns with this “compassionate” guide from a licensed therapist and YouTube personality (John Green).

Get answers to your most common questions about mental health and mental illness — including anxiety, depression, bipolar and eating disorders, and more.

Are u ok? walks readers through the most common questions about mental health and the process of getting help — from finding the best therapist to navigating harmful and toxic relationships and everything in between. In the same down-to-earth, friendly tone that makes her videos so popular, licensed marriage and family therapist and YouTube sensation Kati Morton clarifies and destigmatizes the struggles so many of us go through and encourages readers to reach out for help.

Get answers to your most common questions about mental health and mental illness — including anxiety, depression, bipolar and eating disorders, and more.

Are u ok? walks readers through the most common questions about mental health and the process of getting help — from finding the best therapist to navigating harmful and toxic relationships and everything in between. In the same down-to-earth, friendly tone that makes her videos so popular, licensed marriage and family therapist and YouTube sensation Kati Morton clarifies and destigmatizes the struggles so many of us go through and encourages readers to reach out for help.

Genre:

-

"A humane, compassionate, and extremely helpful guide to the complex world of mental health care. Knowing what's wrong and when to seek help can be life-changing, and Morton's book is packed with tools and tips for navigating life with mental health challenges."John Green, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Turtles All the Way Down and The Fault in Our Stars

-

"An exemplary guide for anyone wondering if they or someone close to them may benefit from mental health therapy."Library Journal

-

"An intuitive handbook that empowers readers to tend to their own mental health...Chapters provide practical tools for handling anxiety, depression, and other mental health difficulties, while also offering powerful insights."Publishers Weekly

-

"[Morton] answers the questions many of us have but don't necessarily feel comfortable asking. This is information everyone can benefit from."Bustle

-

"Compassionate and hopeful."Energy Times

-

"An undeniably essential read."Cultured Vultures

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use