Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

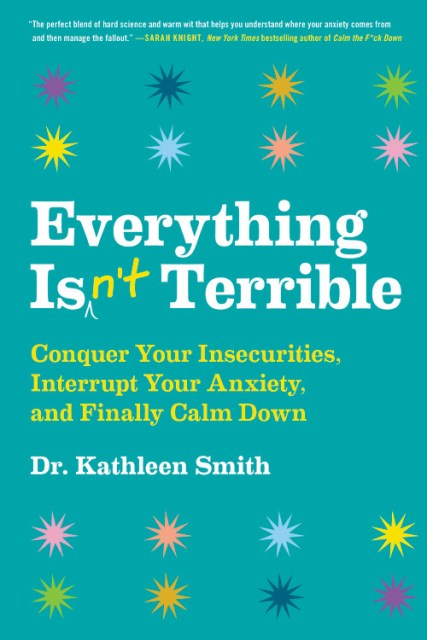

Everything Isn’t Terrible

Conquer Your Insecurities, Interrupt Your Anxiety, and Finally Calm Down

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 31, 2019

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Balance

- ISBN-13

- 9780316492539

Price

$28.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $37.00 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 31, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In the spirit of You Are a Badass and The Life-Changing Magic of Not Giving a F*ck, a helpful and humorous guide to shedding our anxious habits and building a more solid sense of self in an increasingly anxiety-inducing world.

Licensed therapist and mental health writer Dr. Kathleen Smith offers a smart, practical antidote to our anxiety-ridden times. Everything Isn’t Terrible is an informative and practical guide — featuring a healthy dose of humor—for people who want to become beacons of calmness in their families, at work, and in our anxious world. Everything Isn’t Terrible will inspire you to confront your anxious self, take charge of your anxiety, and increase your own capacity to choose how you respond to it. Comprised of short chapters containing anecdotal examples from Smith’s work with her clients, in addition to engaging, actionable exercises for readers, Everything Isn’t Terrible will give anyone suffering from anxiety all the tools they need to finally…calm…down.

Ultimately, living a calmer, less anxious life—one that isn’t terrible—is possible, and with this book you’ll learn how to do it.

Licensed therapist and mental health writer Dr. Kathleen Smith offers a smart, practical antidote to our anxiety-ridden times. Everything Isn’t Terrible is an informative and practical guide — featuring a healthy dose of humor—for people who want to become beacons of calmness in their families, at work, and in our anxious world. Everything Isn’t Terrible will inspire you to confront your anxious self, take charge of your anxiety, and increase your own capacity to choose how you respond to it. Comprised of short chapters containing anecdotal examples from Smith’s work with her clients, in addition to engaging, actionable exercises for readers, Everything Isn’t Terrible will give anyone suffering from anxiety all the tools they need to finally…calm…down.

Ultimately, living a calmer, less anxious life—one that isn’t terrible—is possible, and with this book you’ll learn how to do it.

-

Great news, high-functioning anxious people: relief has arrived! In these pages, Kathleen Smith offers as much wisdom, candor, and helpful homework as you'd get in several therapy sessions -- making this book not only a joy but a great deal. I'll be buying copies for friends.Mary Laura Philpott, nationally bestselling author of IMiss You When I Blink

-

"The perfect blend of hard science and warm wit that helps you understand where your anxiety comes from and then manage the fallout."Sarah Knight, NewYork Times bestsellingauthor of Calm the F*ck Down