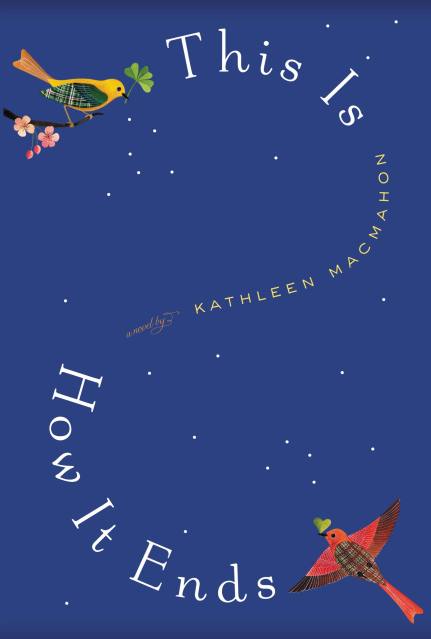

This Is How It Ends

A Novel

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 7, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This is when it begins

Fall, 2008.

This is where it begins

The coast of Dublin, Ireland.

This is why it begins

Bruno, an American, has come to Ireland to search for his roots. Addie, an out-of-work architect, is recovering from heartbreak while taking care of her infirm father. When their worlds collide, they experience a connection unlike any they’ve previously felt, but soon a tragedy will test them-and their newfound love-in ways they never imagined possible.

This is how it ends . . .

A story you will never forget.

Fall, 2008.

This is where it begins

The coast of Dublin, Ireland.

This is why it begins

Bruno, an American, has come to Ireland to search for his roots. Addie, an out-of-work architect, is recovering from heartbreak while taking care of her infirm father. When their worlds collide, they experience a connection unlike any they’ve previously felt, but soon a tragedy will test them-and their newfound love-in ways they never imagined possible.

This is how it ends . . .

A story you will never forget.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 7, 2012

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455511303

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use