Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

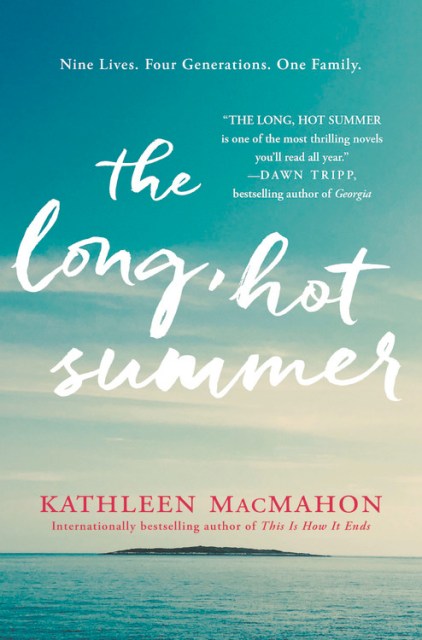

The Long, Hot Summer

A Novel

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.49 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $14.99 $19.49 CAD

- ebook $4.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 3, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Nine Lives. Four Generations. One Family. The MacEntees are no ordinary family.

Determined to be different from other people, they have carved out a place for themselves in Irish life by the sheer force of their personalities.

There’s Deirdre, the aged matriarch and former star of the stage. Her estranged writer husband Manus now lives with a younger man. Their daughter Alma is an unapologetically ambitious television presenter, while Acushla plays the part of the perfect political wife. And there’s Macdara, the fragile and gentle soul of the family. Together, the MacEntees present a glamorous face to the world. But when a series of misfortunes befall them over the course of one long, hot summer, even the MacEntees will struggle to make sense of who they are.

From Kathleen MacMahon, the #1 bestselling author of This is How it Ends, comes this powerful and poignant novel, capturing a moment in the life of one family.

Determined to be different from other people, they have carved out a place for themselves in Irish life by the sheer force of their personalities.

There’s Deirdre, the aged matriarch and former star of the stage. Her estranged writer husband Manus now lives with a younger man. Their daughter Alma is an unapologetically ambitious television presenter, while Acushla plays the part of the perfect political wife. And there’s Macdara, the fragile and gentle soul of the family. Together, the MacEntees present a glamorous face to the world. But when a series of misfortunes befall them over the course of one long, hot summer, even the MacEntees will struggle to make sense of who they are.

From Kathleen MacMahon, the #1 bestselling author of This is How it Ends, comes this powerful and poignant novel, capturing a moment in the life of one family.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jul 3, 2017

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455511327

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use