By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

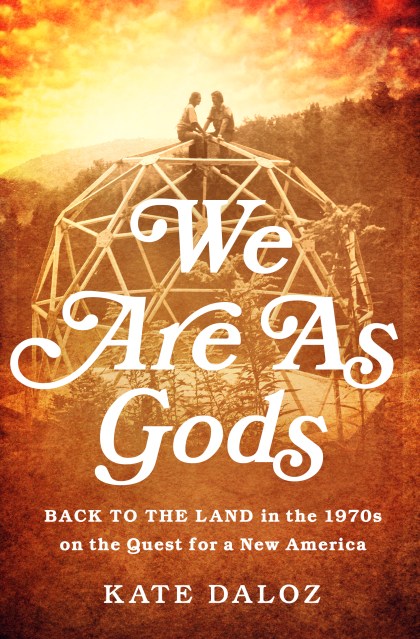

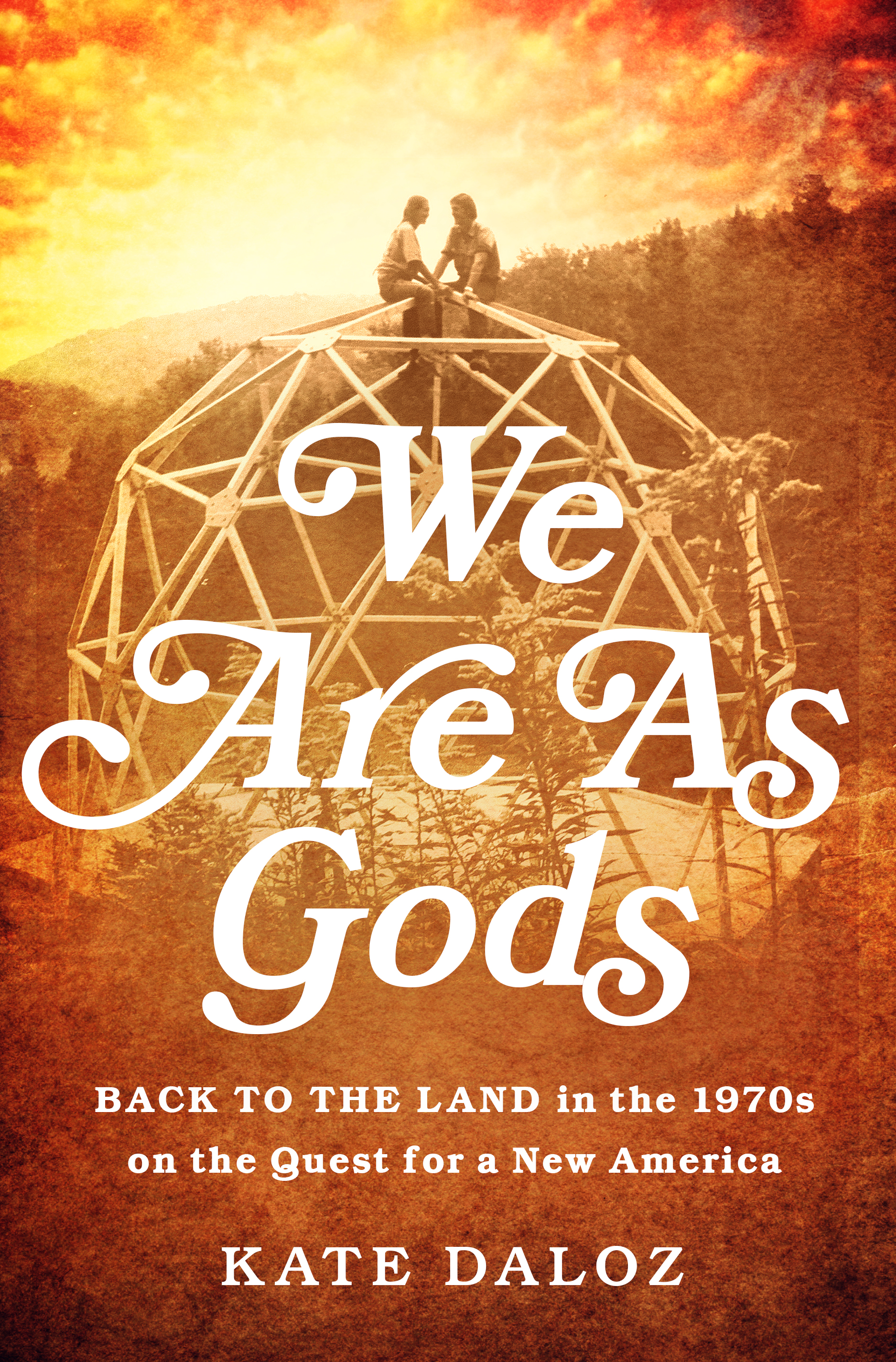

We Are As Gods

Back to the Land in the 1970s on the Quest for a New America

Contributors

By Kate Daloz

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 26, 2016

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610392266

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 26, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

When Loraine, Craig, Pancake, Hershe, and a dozen of their friends came into possession of 116 acres in Vermont, they had big plans: to grow their own food, build their own shelter, and create an enlightened community. They had little idea that at the same moment, all over the country, a million other young people were making the same move — back to the land.

We Are As Gods follows the Myrtle Hill commune as its members enjoy a euphoric Free Love summer. Nearby, a fledgling organic farm sets to work with horses, and a couple — the author’s parents — attempts to build a geodesic dome. Yet Myrtle Hill’s summer ends in panic as they rush to build shelter while they struggle to reconcile their ideals with the somber realities of physical hardship and shifting priorities — especially when one member goes dangerously rogue.

Kate Daloz has written a meticulously researched testament to the dreams of a generation disillusioned by their parents’ lifestyles, scarred by the Vietnam War, and yearning for rural peace. Shaping everything from our eating habits to the Internet, the 1970s Back-to-the-Land movement is one of the most influential yet least understood periods in recent history. We Are As Gods sheds light on one generation’s determination to change their own lives and, in the process, to change the world.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use