Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

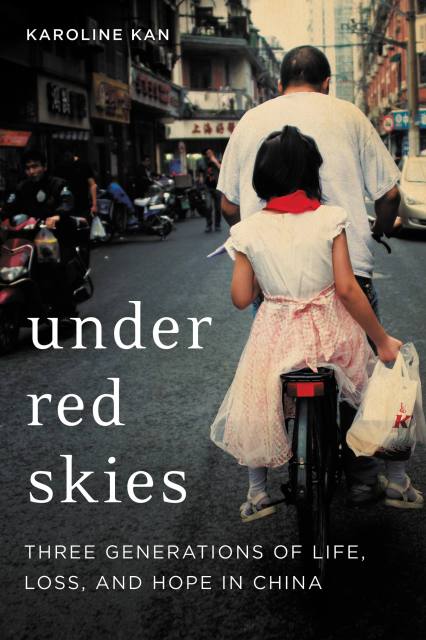

Under Red Skies

Three Generations of Life, Loss, and Hope in China

Contributors

By Karoline Kan

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 12, 2019

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Legacy Lit

- ISBN-13

- 9780316412049

Price

$27.00Price

$35.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.50 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 12, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Through the stories of three generations of women in her family, Karoline Kan, a former New York Times reporter based in Beijing, reveals how they navigated their way in a country beset by poverty and often-violent political unrest. As the Kans move from quiet villages to crowded towns and through the urban streets of Beijing in search of a better way of life, they are forced to confront the past and break the chains of tradition, especially those forced on women.

Raw and revealing, Karoline Kan offers gripping tales of her grandmother, who struggled to make a way for her family during the Great Famine; of her mother, who defied the One-Child Policy by giving birth to Karoline; of her cousin, a shoe factory worker scraping by on 6 yuan (88 cents) per hour; and of herself, as an ambitious millennial striving to find a job–and true love–during a time rife with bewildering social change.

Under Red Skies is an engaging eyewitness account and Karoline’s quest to understand the rapidly evolving, shifting sands of China. It is the first English-language memoir from a Chinese millennial to be published in America, and a fascinating portrait of an otherwise-hidden world, written from the perspective of those who live there.

-

"A heartfelt introduction into China's recent history -- and a rare firsthand dispatch from its millennial generation....For those seeking to understand the future of China and U.S.-China relations, voices like hers are an essential part of the conversation."The Wall Street Journal

-

Marie Claire, "Inspiring Memoirs by Women That Are More Addictive Than Fiction!"

Bustle, "New Memoirs Out In Spring To Help You Welcome Warm-Weather Reading!"

Financial Times, "Readers' Picks for Summer" -

"Vivid and humane, Karoline Kan's memoir of coming of age in China is richly revealing and contemporary, shaped both by the pain of history and the hope for the future - at turns bold and vulnerable, like China itself."Evan Osnos, National Book Award-winning author of Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China and New Yorker staff writer

-

"At first glance, Karoline Kan's Under Red Skies is a simple coming-of -age story. A young girl from a poor family grows up, goes to university, falls in love and gets her heart broken (repeatedly), and finally triumphs as a journalist. But contained within is a sharply observed critique of all that is dysfunctional in Chinese society. You can learn more about modern China through this compulsively readable memoir than from many weightier tomes."Barbara Demick, National Book Award finalist and author of Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea

-

"Karoline Kan's intimate portrait of growing up in contemporary China opens a new window onto a country going through lightning-fast change."Edward Wong, International Correspondent and Former Beijing Bureau Chief, The New York Times

-

"Under Red Skies is a beautiful look at the struggles of China's fast-changing society. In Karoline's inspiring and heartfelt stories of her family, she voices how much Chinese people have overcome. This book should be read by people from all corners of the world if they want to know the real story of China."Xinran, author of The Good Women of China

-

"Karoline Kan's Under Red Skies is an engrossing account of a rapidly changing China seen through the eyes of an imaginative, ambitious young woman... An intimate coming-of-age story, this book should be read by anyone seeking to understand the aspirations and frustrations of young people in China today."Leta Hong Fincher, author of Betraying Big Brother: The Feminist Awakening in China

-

"A fascinating memoir about three generations of Chinese women. Whereas classics like Wild Swans end with the Cultural Revolution, Under Red Skies picks up where Jung Chang leaves off in this look at contemporary Chinese life and history as it changes before our eyes."Lijia Zhang, author of Socialism is Great! A Worker's Memoir of The New China

-

"With her revealing and introspective account of growing up in post-1989 China, Kan fills a void in contemporary literature on the country. While the profound societal shakeup that unfolded during that period has left everyone of her generation with a remarkable story, few have possessed such skill and courage in telling theirs."Eric Fish, author of China?s Millennials: The Want Generation

-

"Poignant, humane, and insightful, [Under Red Skies] brings the extraordinary story of the last fifty years in China vividly alive. The Kan family's struggles to survive and prosper through many adversities, largely inflicted on them by government, are a moving testament to the resilience and determination of three generations of women."Isabel Hilton, OBE, founder of China Dialogue and author of The Search for the Panchen Lama

-

"A remarkable multigenerational memoir that clearly explores 'the real China-its beauty and ugliness, the weird and familiar, the joyful and sad, progressive and backward at the same time.'"Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

-

"Kan presents an engaging debut memoir that would make an excellent book club choice."Library Journal

-

"[Kan is] an eloquent, restrained and gripping writer."TruthDig

-

"[Kan] has written the gripping autobiography of a generation--and a superpower--caught between tradition and ambition."The Economist

-

"Razor sharp... [this book is a] coherent explanation of the dizzying changes that have affected daily life in contemporary China."The South China Morning Post

-

"[Kan] is a clear and straightforward writer, walking readers through her own life and that of her family... An impressive [story]."Asian Review of Books

-

"Stunning."Remotelands.com

-

"It's enjoyable to get to know Kan on the page; she tells moving family tales as well as poignant personal stories, and serves as an engagingly candid guide to the fascinating generation she is a part of. She and they have faced the distinct challenge of coming of age as their country experiences its own dizzying transformations."New York Times