By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

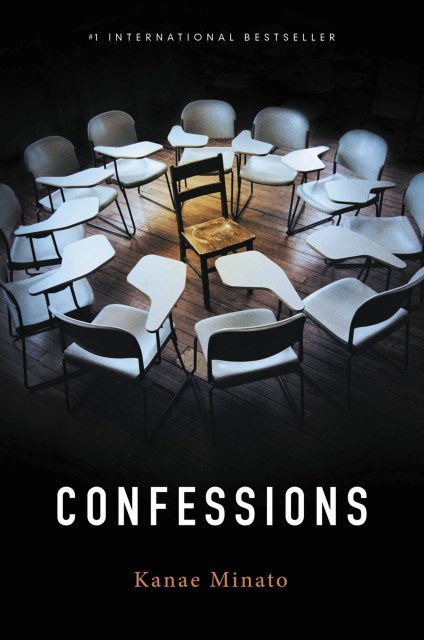

Confessions

Contributors

By Kanae Minato

Translated by Stephen Snyder

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 19, 2014

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Mulholland Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316200912

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 19, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In this international bestselling thriller, a former teacher delivers her final lesson to her students—including the two children that murdered her daughter.

After calling off her engagement in the wake of a tragic revelation, Yuko Moriguchi had nothing to live for except her only child, four-year-old child, Manami. Now, following an accident on the grounds of the middle school where she teaches, Yuko has given up and tendered her resignation.

But first she has one last lecture to deliver. She tells a story that upends everything her students ever thought they knew about two of their peers, and sets in motion a diabolical plot for revenge.

Narrated in alternating voices, with twists you'll never see coming, Confessions probes the limits of punishment, despair, and tragic love, culminating in a harrowing confrontation between teacher and student that will place the occupants of an entire school in danger. You'll never look at a classroom the same way again.

After calling off her engagement in the wake of a tragic revelation, Yuko Moriguchi had nothing to live for except her only child, four-year-old child, Manami. Now, following an accident on the grounds of the middle school where she teaches, Yuko has given up and tendered her resignation.

But first she has one last lecture to deliver. She tells a story that upends everything her students ever thought they knew about two of their peers, and sets in motion a diabolical plot for revenge.

Narrated in alternating voices, with twists you'll never see coming, Confessions probes the limits of punishment, despair, and tragic love, culminating in a harrowing confrontation between teacher and student that will place the occupants of an entire school in danger. You'll never look at a classroom the same way again.

-

"Far deeper and larger, though no less entertaining, than expected. A nasty little masterpiece...that rare creature in fiction: an ambitious exploration into the darkest corners of human nature ... that is alsoa crackling good yarn ... Resistance to the novel's narrative momentum is futile; I read it in a single sitting ... Along the way I learned much--more, if truth be told, than I felt emotionally prepared to learn--about the damage inflicted by adults upon children, and the ways in which the young sometimes return it in kind, twisted and magnified... Books like CONFESSIONS can make you vibrate with happiness."Kevin Nance, Chicago Tribune

-

"A Japanese Gone Girl...CONFESSIONS will drop your jaw right to the floor. The most delightfully evil book you'll read this year. A gut-wrenching thrill-ride with clean, high-impact language."Steph Cha, Los Angeles Times

-

"A chilling and effective psychological thriller...a reader is almost certain to be caught off guard more than once... Implacable, relentless and stunning."Tom Nolan, Wall Street Journal

-

"Minato's intricate plotting and unnervingly understated sentences make the horrors follow each other as logically as pearls on a string."Annalisa Quinn, NPR.org

-

"Captivating...as the murders grow bloodier and bloodier, the characters more and more twisted, we find ourselves fascinated and repulsed, unable to look away...CONFESSIONS undercuts prejudices with force and ferocity."Becca Rothfield, New Republic

-

"An outstanding debut. Minato spotlights the dysfunction that can fester beneath the tidy surface of Japanese society--as well as the searing fury of a mother's love gone wrong."Publishers Weekly (starred, boxed review)

-

"This long-awaited English translation is a spellbinding read, a fascinating peek into modern Japanese society, and a glimpse into the dark corners of the human psyche."Booklist (starred review)

-

"CONFESSIONS is a dark, disturbing tale that twists and turns on itself like an Escher print. Just when you think you know where this thriller is going, Kanae Minato throws back the curtain to reveal another face to the mystery. A Lord of the Flies for the modern world, Minato mines the dark specter of youth, while simultaneously demonstrating some of the deeper perils of our global culture."Jenny Milchman, Mary Higgins Clark Award-winning author of Cover of Snow

-

"This award-winning debut novel is a creepy and mesmerizing psychological thriller that challenges the conventions of right vs. wrong, good vs. evil, and law vs. justice. . . . Minato has pieced together an intriguing puzzles that will keep readers glued to their seats."Library Journal

-

"A dark, dystopic portrait of Japanese adolescence gone wrong. If Albert Camus had written Heathers, it would have looked a lot like this."Alex Marwood, Edgar Award-winning author of The Wicked Girls

-

"Kanae Minato is a brilliant storyteller, and CONFESSIONS is a superb and haunting work. As Minato expertly shifts the perspective from one character to the next, each change in perspective lends a startling new dimension to a gripping and profoundly unsettling tale. It's a novel I'll think about for a very long time."Emily St. John Mandel, author of The Lola Quartet and Singer's Gun

-

"Taut, unsettling and relentlessly engaging, CONFESSIONS is a book with claws, in more sense than one. I defy any fan of smart, unconventional crime writing to set this novel aside once they've started it."Simon Lelic, CWA John Creasey Dagger Award-shortlisted author of A Thousand Cuts

-

"Don't be fooled by the hypnotic beauty of Kanae Minato's prose. As the characters in CONFESSIONS are stripped of their secrets, the novel reveals its audacious dark heart. A pitch-perfect, riveting read."Hilary Davidson, Anthony Award-winning author of The Damage Done and Evil in All Its Disguises

-

"Brilliantly original and chilling."David Morrell, New York Times bestselling author of Murder as a Fine Art

-

"It's time to unretire all of those back-of-the-book words that lost their meaning over the years-unputdownable, riveting, searing. CONFESSIONS is some uncanny kind of tour de force, and everyone should read it."Charles Finch, Agatha Award-nominated author of The September Society and The Last Enchantments

-

"I read this riveting tale of murder, revenge and madness in one sitting, and it took my breath away. I don't think I've ever read anything quite like it. CONFESSIONS will grab you from the first chapter and won't let go until its stunning conclusion. Pick up this book when you have a few hours to read, because you won't be able to put it down."Wendy Webb, author of The Vanishing and The Tale of Halcyon Crane

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use