Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

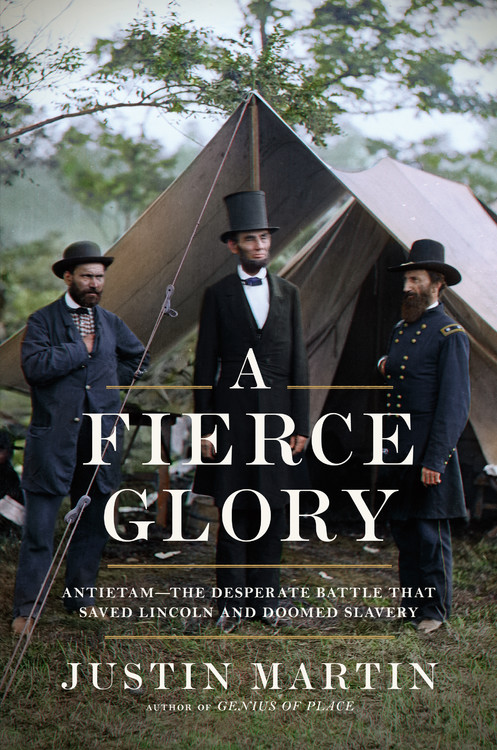

A Fierce Glory

Antietam--The Desperate Battle That Saved Lincoln and Doomed Slavery

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 11, 2018

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306825255

Price

$38.00Price

$49.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $38.00 $49.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 11, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The epic battle, fought near Sharpsburg, Maryland, was a Civil War turning point. The South had just launched its first invasion of the North; victory for Robert E. Lee would almost certainly have ended the war on Confederate terms. If the Union prevailed, Lincoln stood ready to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. He knew that freeing the slaves would lend renewed energy and lofty purpose to the North’s war effort. Lincoln needed a victory to save the divided country, but victory would come at a price. Detailed here is the cannon din and desperation, the horrors and heroes of this monumental battle, one that killed 3,650 soldiers, still the highest single-day toll in American history.

Justin Martin, an acclaimed writer of narrative nonfiction, renders this landmark event in a revealing new way. More than in previous accounts, Lincoln is laced deeply into the story. Antietam represents Lincoln at his finest, as the grief-racked president–struggling with the recent death of his son, Willie–summoned the guile necessary to manage his reluctant general, George McClellan. The Emancipation Proclamation would be the greatest gambit of the nation’s most inspired leader. And, in fact, the battle’s impact extended far beyond the field; brilliant and lasting innovations in medicine, photography, and communications were given crucial real-world tests. No mere gunfight, Antietam rippled through politics and society, transforming history.

A Fierce Glory is a fresh and vibrant account of an event that had enduring consequences that still resonate today.

-

"A colorful, deft, beautifully paced account of the bloodiest battle in American history. Justin Martin carefully tends Antietam's 'glowing embers,' approaching the day on the ground and from every angle."--Stacy Schiff, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Cleopatra and The Witches

-

"More than the repulse of a Confederate invasion, the Union victory at Antietam paved the way for black freedom--thus proving, in its way, the most important battle of the Civil War. Appropriately, A Fierce Glory is more than a military history (although it depicts the actual fighting vividly). Martin has culled a vast array of sources to explore the political, religious, medical, and, ultimately, the societal impact of Antietam. A highly original work."--Harold Holzer, winner of the Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

-

"What an achievement! Both panoramic and intimate in scale, it situates Antietam within the context of Civil War history but also takes the reader in close, face to face with the personal reality of 19th century warfare."--Amanda Vaill, author of Hotel Florida: Truth, Love, and Death in the Spanish Civil War

-

"With a great eye for colorful detail, Martin has pulled off the feat of contextualizing the battle for a general audience. I learned something new on every page--not just about Lincoln, McClellan, and Lee, but about medical pioneers Clara Barton and Jonathan Letterman, photographer Alexander Gardner, and the fates of average soldiers on both sides. An absorbing read."--Jonathan Alter, New York Times bestselling author of The Promise: President Obama, Year One

-

"Martin has given us an engrossing, important new look at Antietam, making a convincing case that the outcome had more impact on the course of the war, and on U.S. history, than any other Civil War engagement."--Marc Leepson, author of Desperate Engagement: How a Little-Known Civil War Battle Saved Washington, D.C., and Changed American History

-

"Martin takes you to the fabled Antietam battlefield in an engagingly written 'you are there' style that has you virtually feeling the bullets whizzing above your head. This is no dry military history or conventional Civil War book but a riveting group biography that delves into the hearts and minds of a number of colorful, larger-than-life characters, all of it placed in the context of the fateful deliberations of Lincoln over issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation. A tour de force."--John Oller, author of The Swamp Fox and American Queen

-

"In this succinct, highly readable book, spiced with telling anecdotes and vivid character sketches, Martin seamlessly interweaves a clear, suspenseful account of the battle with a careful depiction of Lincoln's road to emancipation."--Michael Burlingame, award-winning Lincoln scholar and author of Lincoln: A Life (2 vols.)

-

"Martin is at his best relating the intersection of the experiences of individual soldiers and the places in which they found themselves as the battle progressed...A readable introduction for those unfamiliar with this crucial battle."Library Journal

-

"If you're looking for an Antietam book with minute-by-minute movements of regiments and brigades, look elsewhere-this isn't a 'right-flank, left-flank' account. Instead, you'll find an exquisite, compelling narrative, with Martin serving as your tour guide at the Bloody Lane, the West Woods, the 40-Acre Cornfield and elsewhere...Unlike other Antietam books, Abraham Lincoln...is deeply embedded in the narrative."John Banks' Civil War Blog

-

"Not only does one get the story of the battle but also that of Lincoln and his Proclamation...It is highly readable and captures the drama of our bloodiest single day and its momentous result."New York Journal of Books

-

"In A Fierce Glory author Justin Martin well portrays the horror of Civil War combat from the common soldier's perspective. His deft human touch, evident throughout the narrative, makes for a complete sensory experience."Wall Street Journal

-

"In a war that redefined carnage, Antietam stands out...Martin does not miss any key elements of the battle, nor does he neglect the larger social and political undertones...A multi-faceted story that brings to bear a range of emotions surrounding the complicated events depicted...Anyone seeking a fresh telling of the human cost, anyone questing for larger meaning within this particularly bloody Civil War battle, will find A Fierce Glory to be a worthwhile read."Washington Independent Review of Books

-

"A Fierce Glory accommodates perspectives largely absent from older accounts of the Civil War, including the multi-ethnicity of both armies and the presence in the ranks of several women passing as men."Milwaukee Shepherd-Express

-

"Martin avoids clinical military assessments and instead imbues the story of Antietam with small personal details about the very real people-from private to president-whose fates changed with the outcome...Martin argues intriguingly that the Union victory-snatched from stalemate only by the eventual Confederate retreat-served as the true turning point of the war...Novelistic prose, supported by thorough documentation and photos, packs an additional wallop, bringing home the battle's high human cost...Martin's fantastic recreation of this significant battle, with its focus on humanity, will resonate with both Civil War novices and more knowledgeable readers."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

"Martin has written a personal and approachable book about the great and terrible Battle of Antietam. His narrative style is breezy and conversational, quite different from the usual voice on this subject, but with it he successfully interprets some important political and military themes for a general-reader audience...A new and different take on the Battle of Antietam."Antietam on the Web

-

"Almost every angle imaginable on the Civil War has been studied and yet authors continue to bring forth different perspectives. This is the case with Justin Martin's A Fierce Glory...[An] excellent book that looks at the Battle of Antietam from a different angle."Collected Miscellany

-

"Although there are many books on the Battle of Antietam, this one stands out for its superb use of first-hand participant accounts. The author weaves the broader story of the battle into the work in a seamless manner...In addition, the far-ranging consequences of the battle are discussed at length. The result is a work that engages readers and retains their interest page after page...A worthy addition to the works available on Antietam and the American Civil War."Military Heritage