By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

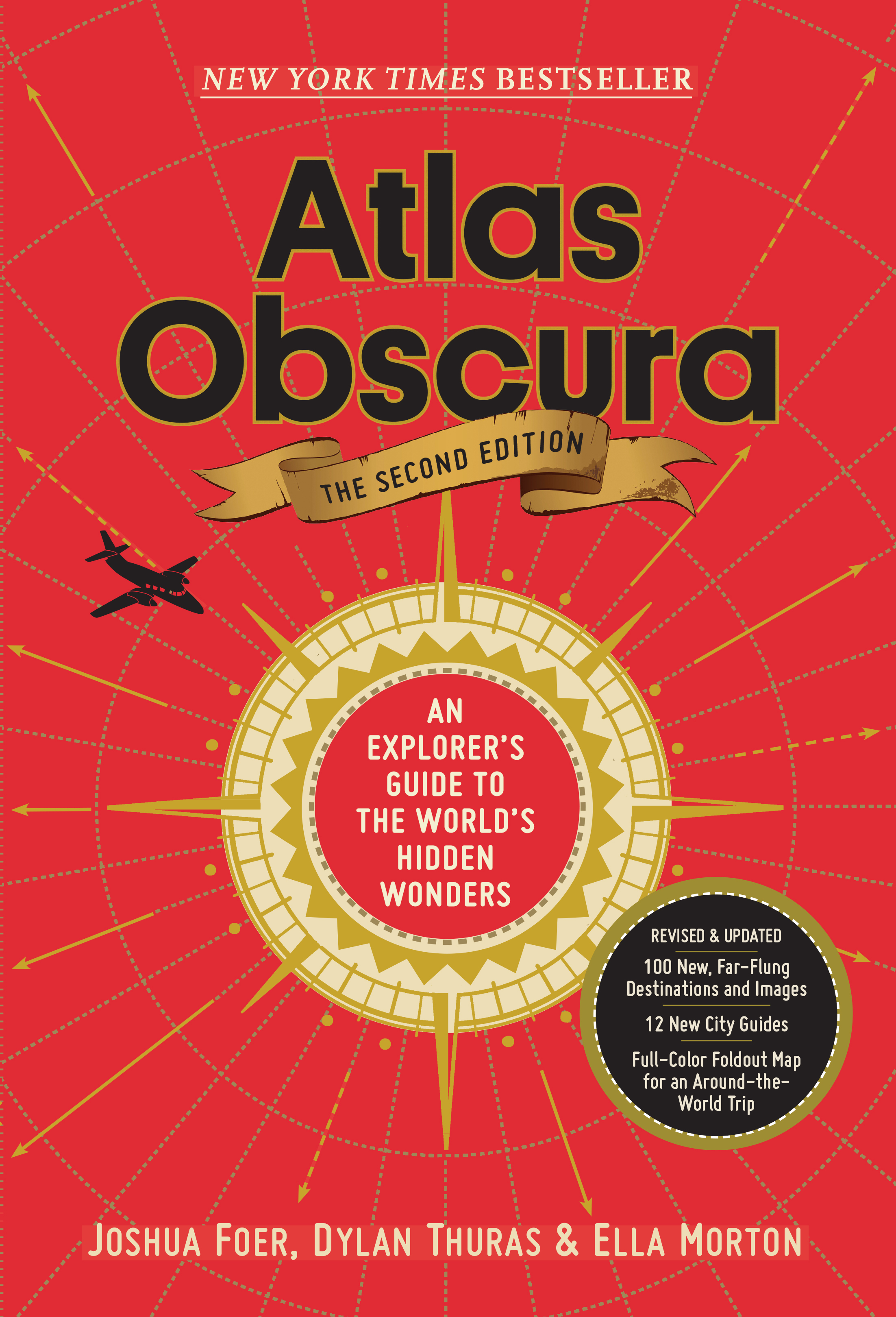

Atlas Obscura, 2nd Edition

An Explorer's Guide to the World's Hidden Wonders

Contributors

By Joshua Foer

By Ella Morton

By Dylan Thuras

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 15, 2019

- Page Count

- 480 pages

- Publisher

- Workman Publishing Company

- ISBN-13

- 9781523506484

Price

$40.00Price

$50.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover (Revised) $40.00 $50.00 CAD

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 15, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Discover wonder.

“A wanderlust-whetting cabinet of curiosities on paper.”— New York Times

Inspiring equal parts wonder and wanderlust, Atlas Obscura is a phenomenon of a travel book that shot to the top of bestseller lists when it was first published and changed the way we think about the world, expanding our sense of how strange and marvelous it really is.

This second edition takes readers to even more curious and unusual destinations, with more than 100 new places, dozens and dozens of new photographs, and two very special features: twelve city guides, covering Berlin, Budapest, Buenos Aires, Cairo, London, Los Angeles, Mexico City, Moscow, New York City, Paris, Shanghai, and Tokyo. Plus a foldout map with a dream itinerary for the ultimate around-the-world road trip. More a cabinet of curiosities than traditional guidebook, Atlas Obscura revels in the unexpected, the overlooked, the bizarre, and the mysterious. Here are natural wonders, like the dazzling glowworm caves in New Zealand, or a baobob tree in South Africa so large it has a pub inside where 15 people can sit and drink comfortably. Architectural marvels, including the M. C. Escher–like stepwells in India. Mind-boggling events, like the Baby-Jumping Festival in Spain—and no, it’s not the babies doing the jumping, but masked men dressed as devils who vault over rows of squirming infants.

Every page gets to the very core of why humans want to travel in the first place: to be delighted and disoriented, uprooted from the familiar and amazed by the new. With its compelling descriptions, hundreds of photographs, surprising charts, maps for every region of the world, and new city guides, it is a book you can open anywhere and be transported. But proceed with caution: It’s almost impossible not to turn to the next entry, and the next, and the next.

Genre:

Series:

-

Colin McEnroe, WNPRPraise for the second edition of Atlas Obscura:An Explorer's Guide to the World's Hidden Wonders “The Second Edition of Atlas Obscura is a hefty book but one that the world traveler in your life will love. There are hidden gems with over 100 more places added from the original. Travel through Budapest, Moscow, Tokyo, and more with the turn of the page and showcase all the curiosities this world holds.” — The Daily Beast “Beholding hundreds of off-the-beaten-path gems, this book is a treasure chest of wanderlust where readers are transported to places they’re certain to have never encountered.” — Marie Claire “The second edition of “Atlas Obscura” is a gift so enthralling that it may draw the recipient into a kind of extended trance. Crammed fore-to-aft with “the world’s hidden wonders,” this collaboration by Joshua Foer, Dylan Thuras and Ella Morton features mesmerizing photos, maps, drawings, info and addresses. On one page there’s a Thai monk standing in saffron serenity in a village temple built of brown and green beer bottles; on another a bust of Vladimir Lenin, erected in 1958 by Soviet scientists who made it to Antarctica’s “Southern Pole of Inaccessibility.” If you can get there (the authors have advice about that), you may find, depending on the weather, only the top of the tyrant’s head poking from the snow.” — Wall Street Journal "Satisfy your wanderlust and plan your next travel adventure with the help of this brilliantly illustrated guide." —Car and Driver Magazine

Praise for the first edition of Atlas Obscura:An Explorer's Guide to the World's Hidden Wonders

“A wanderlust-whetting cabinet of curiosities on paper” B>The New York Times

“This book is as curious and enthralling as the world it covers. Each page reveals some hidden realm—a realm that is frightening, or funny, or magical, or simply mad, but that always leaves the reader in wonder.”

B>DAVID GRANN, author of Killers of the Flower Moon“I thought I had seen most of the interesting bits of the world. Atlas Obscura showed me that I was wrong. It's the kind of book that makes you want to pack in your workaday life and head out to places you'd never have dreamed of going, to see things you could not even have imagined. A joy to read and to reread.”

B>NEIL GAIMAN, author of Sandman and American Gods“Atlas Obscura is a joyful antidote to the creeping suspicion that travel these days is little more than a homogenized corporate shopping opportunity. Here are hundreds of surprising, perplexing, mind-blowing, inspiring reasons to travel a day longer and farther off the path. . . . Bestest travel guide ever.”

B>MARY ROACH, author of Stiff and Gulp“My favorite travel guide! Never start a trip without knowing where a haunted hotel or a mouth of hell is!”

B>GUILLERMO DEL TORO, filmmaker, Pan’s Labyrinth“Fair warning: It's addictive.” B>NPR, “Cosmos & Culture”

“In this gorgeous collection, the celebrated Atlas Obscura website is condensed into 480 pages of awe-inspiring destinations. For lovers of history and exploration, the striking color photographs will spark immediate wanderlust.” B>Entertainment Weekly

“Odds are you won’t get past three pages without being amazed at something truly strange that you didn’t know existed.” B>San Francisco Chronicle

“Richly illustrated, delightfully strange, this compendium of off-beat destinations should spark many adventures, both terrestrial and imaginary.” B>Boston Globe

“This book is PACKED with wonderful, amazing, fascinating places all around the world. This is the perfect gift for the person who thinks they’ve done it all and seen it all because this shows that there’s so much more in the world to explore. It’s a wonderful, wonderful coffee table book.” B>NBC, “TODAY”

“A perfect tome for the armchair explorer and the actual traveler alike.” B>Austin American Statesman

“Whether describing a Canadian museum that showcases world history through shoes, a pet-casket company that will also sell you a unit for your severed limb, a Greek snake festival, or a place in the Canary Islands where inhabitants communicate through whistling, the authors have compiled an enthralling range of oddities. Featuring full-color illustrations, this hefty and gorgeously produced tome will be eagerly pored over by readers of many ages and fans of the original website.”B>Booklist (Starred Review)

“If this compendium of the weirdest, wackiest, and most wonderful destinations on the planet doesn't fill you with insatiable wanderlust, then you need to check your pulse.” B>mental_floss

“This is the fun way, a deep dive (sometimes literally) into places you’d never find otherwise, the weird and wild wonders of the world.” B>WIRED

“The book is for people who prefer to live like locals when they travel, seek out new cultures on vacation, or just prefer the weirdness of history to traditional by-the-book experiences. Even if you can’t travel, Atlas Obscura is a window into places you’d otherwise never know existed.” B>lifehacker

“A travel guide for the most adventurous of tourists . . . a wonderful browse [for] armchair travelers who enjoyed Brandon Stanton’s Humans of New York and Frank Warren’s PostSecret.” B>Library Journal

“The most addictive book of the year.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use