By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

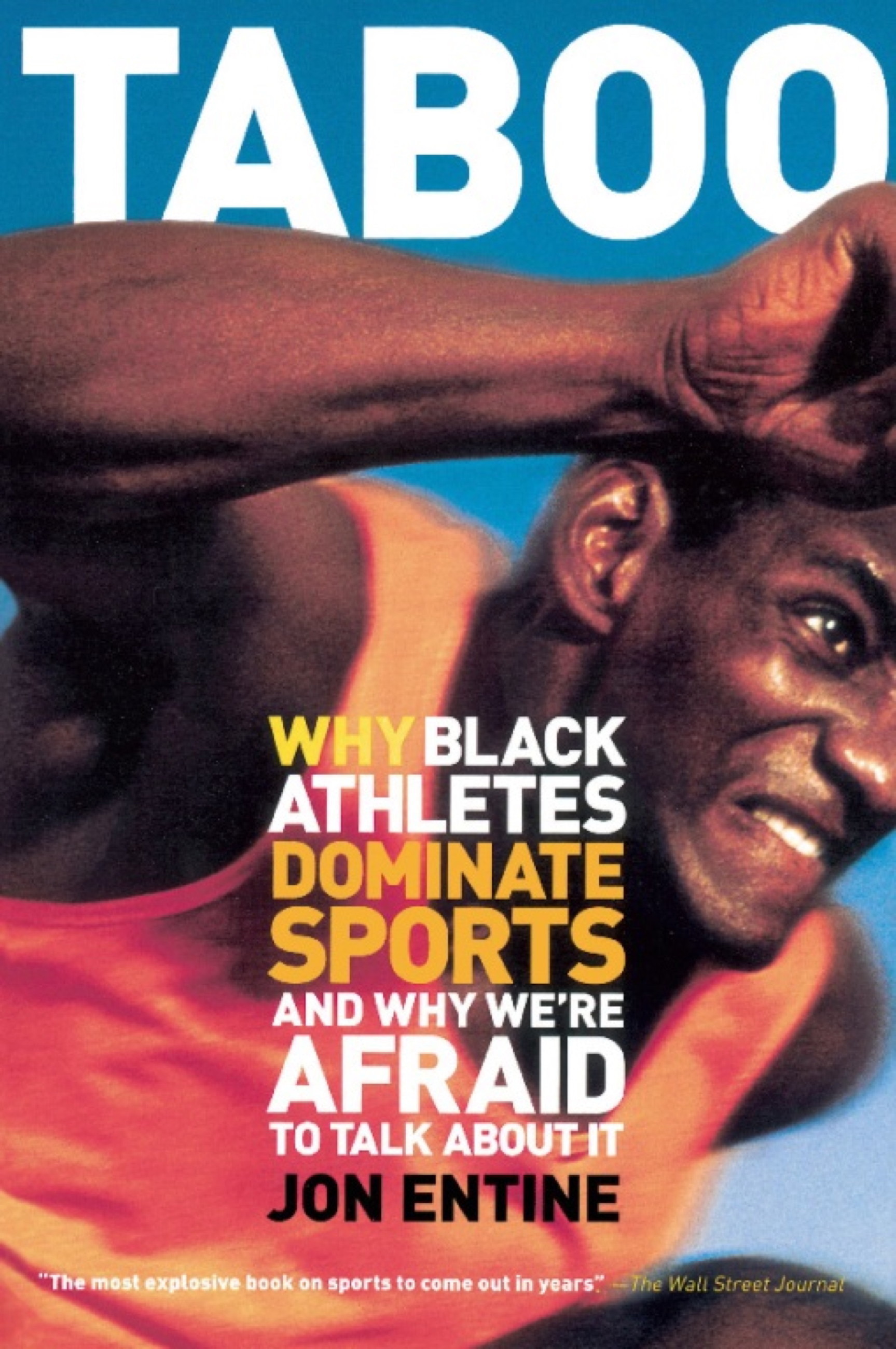

Taboo

Why Black Athletes Dominate Sports And Why We're Afraid To Talk About It

Contributors

By Jon Entine

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 5, 2008

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786724505

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 5, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In virtually every sport in which they are given opportunity to compete, people of African descent dominate. East Africans own every distance running record. Professional sports in the Americas are dominated by men and women of West African descent. Why have blacks come to dominate sports? Are they somehow physically better? And why are we so uncomfortable when we discuss this? Drawing on the latest scientific research, journalist Jon Entine makes an irrefutable case for black athletic superiority. We learn how scientists have used numerous, bogus “scientific” methods to prove that blacks were either more or less superior physically, and how racist scientists have often equated physical prowess with intellectual deficiency. Entine recalls the long, hard road to integration, both on the field and in society. And he shows why it isn’t just being black that matters—it makes a huge difference as to where in Africa your ancestors are from.Equal parts sports, science and examination of why this topic is so sensitive, Taboois a book that will spark national debate.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use