Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

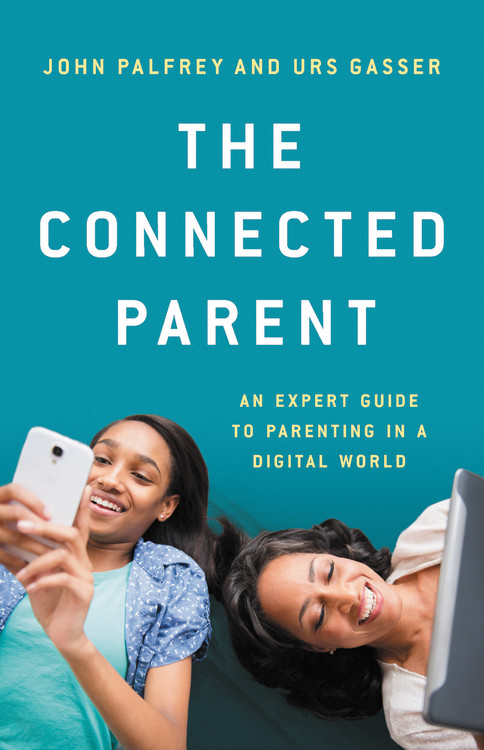

The Connected Parent

An Expert Guide to Parenting in a Digital World

Contributors

By John Palfrey

By Urs Gasser

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 6, 2020

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541618022

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 6, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

An essential guide for parents navigating the new frontier of hyper-connected kids.

Today’s teenagers spend about nine hours per day online. Parents of this ultra-connected generation struggle with decisions completely new to parenting: Should an eight-year-old be allowed to go on social media? How can parents help their children gain the most from the best aspects of the digital age? How can we keep kids safe from digital harm? John Palfrey and Urs Gasser bring together over a decade of research at Harvard to tackle parents’ most urgent concerns. The Connected Parent is required reading for anyone trying to help their kids flourish in the fast-changing, uncharted territory of the digital age.

-

"Palfrey and Gasser offer a thoughtful and necessary consideration of the difficulties of parenting digital natives, and how to contend with them. They show us how to remain connected to our kids, and to our humanity, in an age in which our kids live, learn, and struggle as much online as they do in the physical world."Jonathan Zittrain, Harvard University

-

"This book is the must-read guide for parents as they navigate their children's journey in all things digital. No duo is more suited for the task -- as esteemed educators, prominent researchers, and as parents of teens themselves, Palfrey and Gasser help guide parents on their shepherding of their kids through responsible, thoughtful, and rewarding uses of digital tools. The book is filled with tips on how to be effective partners and interlocutors in the process of working with teenagers as they game, learn, befriend, and experiment online. The book illuminates on questions about privacy, safety, and overuse of digital tools. This is the guide that I wish I had when I was parenting teens."Danielle Keats Citron, author of Hate Crimes in Cyberspace

-

"I can't imagine a more important book for a caretaker or parent of a child or young adult. Many parents think they understand the online world their children navigate for hours every day, but this moment is more complex than any other in the digital age. Children and young adults experience ideas, emotions, and feelings of belonging based on how they experience their online world. Palfrey and Gasser offer clear direction and vital insight on understanding their digital space and making it safe, fun, and productive. The Connected Parent is a must read for anyone with a child (and those preparing to have one)."Farah Pandith, author and former U.S. diplomat

-

"The Connected Parent comes at a time when the practice of parenting has been made much more challenging as children spend increasing amounts of time with screens, technology, and the world around them. Parents have been overwhelmed by fear-mongering, misinformation, and confusion when it comes to their children's engagement with the digital world. The Connected Parent is a book that many parents will find refreshing, informative, and grounded in the familiar realities of daily life. Drawing from some of the best research in the world and their deep subject matter expertise John Palfrey and Urs Gasser make a significant contribution to the ongoing conversation about how to help our children use technology more effectively while also supporting their health, happiness, and readiness for the future."S. Craig Watkins, author of The Digital Edge: How Black and Latino Youth Navigate Digital Inequality

-

"Parents and any other adults involved in the lives of young people today need advice and wisdom about how to protect and how to assist 'digital natives' who often live as much online as in person. Internationally recognized experts John Palfrey and Urs Gasser provide a rare combination of practical, concrete wisdom and deeply-researched knowledge addressing fears and benefits from social media and other digital worlds of children and teens. Their accessible insights will help today's adults ensure safety, address anxieties and harassment, and enhance learning and civic engagement while also deepening meaningful connections with the young people in their lives."Martha Minow, Harvard University

-

"If you are a parent, educator, or clinician, or in fact anyone interested in healthy development in our modern digital age, The Connected Parent is a compelling, comprehensive, and clear presentation of the latest science illuminating how life on the small screen influences our children and adolescents' lives. Building a solid foundation of research and practical advice, John Palfrey and Urs Gasser offer an insightful and effective approach to helping our youth grow with resilience, relational connection, and a wise approach to being engaged citizens in an uncertain and ever-changing world."Daniel J. Siegel, M.D., New York Times-bestselling author of The Developing Mind

-

"The Connected Parent is a lucid guide for parents everywhere who aren't sure what to make of our hyperconnected world and its effects on their children. Palfrey and Gasser offer balanced answers to some of the issue's trickiest puzzles: How much screen time is too much? Can my kids become addicted to video games and social media? Can an online social life be nourishing in the same way as offline social lives have been for millennia? My favorite part of the book, though, was its focus on remedies -- on the importance of exposing kids to the kinds of diversity, opportunities to learn, and civic life that are often hard to find online, but represent the best experiences in our real, offline world. Highly recommended."Adam Alter, marketing and psychology professor, New York University Stern School of Business, New York Times-bestselling author of Irresistible and Drunk Tank Pink

-

"The authors effectively combine research and anecdote, and they carefully sum up their recommendations at the end of each chapter along with a list of common questions. Because the influence of technology will only grow in coming years, this thorough investigation is a welcome addition to the parenting shelves."Kirkus