Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

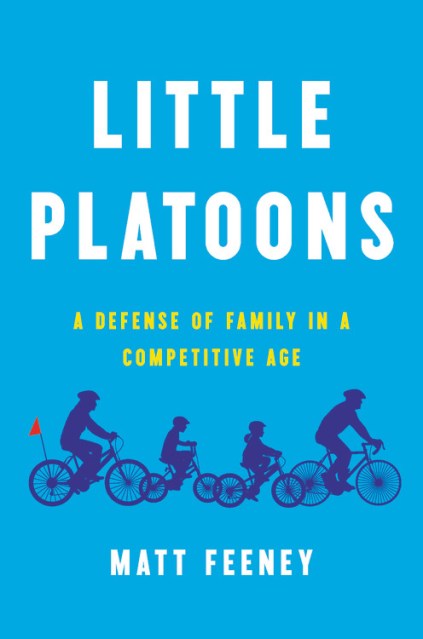

Little Platoons

A Defense of Family in a Competitive Age

Contributors

By Matt Feeney

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 9, 2021

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541645592

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 9, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Parents naturally worry about the future. They want to prepare their children to compete in an uncertain world. But often, argues political philosopher and father of three Matt Feeney, today’s worried parents surrender their family’s autonomy to gain a leg up in this competition.

In the American ideal, family life is a sacred and private sphere, distinct from the outside world. But in our hypercompetitive times, Feeney shows, parents have become increasingly willing to let the inner life of the family be colonized by outside forces that promise better futures for their kids: prestigious preschools, “educational” technologies, youth sports leagues, a multitude of enrichment activities, and — most of all — college. A provocative, eye-opening book for any parent who suspects their kids’ stuffed schedules are not serving their best interests, Little Platoons calls us to rediscover the distinctive, profound solidarity of family life.

-

"Little Platoons offers revelatory insights into the workings of institutions that cluster around the family and feed off it, turning our most intimate loyalties to bureaucratic purposes while reshaping parents and children alike into compliant drones. In this most wise and spirited book, Matt Feeney recalls us to the family's inherent potential-as a little conspiracy of defiance, a nursery of secret joys and private meanings. Inside jokes! Along the way, he scrambles our culture war categories of progressive and conservative. To read Little Platoons is to experience a critical awakening of the rarest kind, one that affirms our love for our own and fills the breast with a new determination. Here is the work of a father-judicious, humane, and ready to fight."Matthew B. Crawford, New York Times-bestselling author of Shop Class as Soulcraft

-

"Little Platoons is a brilliant, acutely observant analysis of why parents are slowly driving themselves crazy as they try to launch their kids into satisfying and successful futures. Matt Feeney writes as a fellow sufferer, with a style that is so welcoming and engaging that you want him to be your best friend."Barry Schwartz, author of The Costs of Living, The Paradox of Choice, and Practical Wisdom