By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

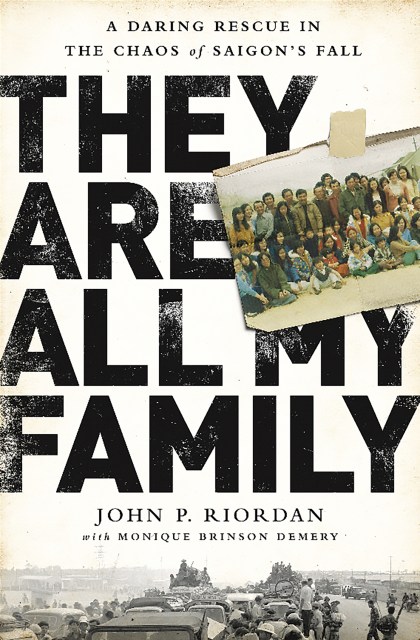

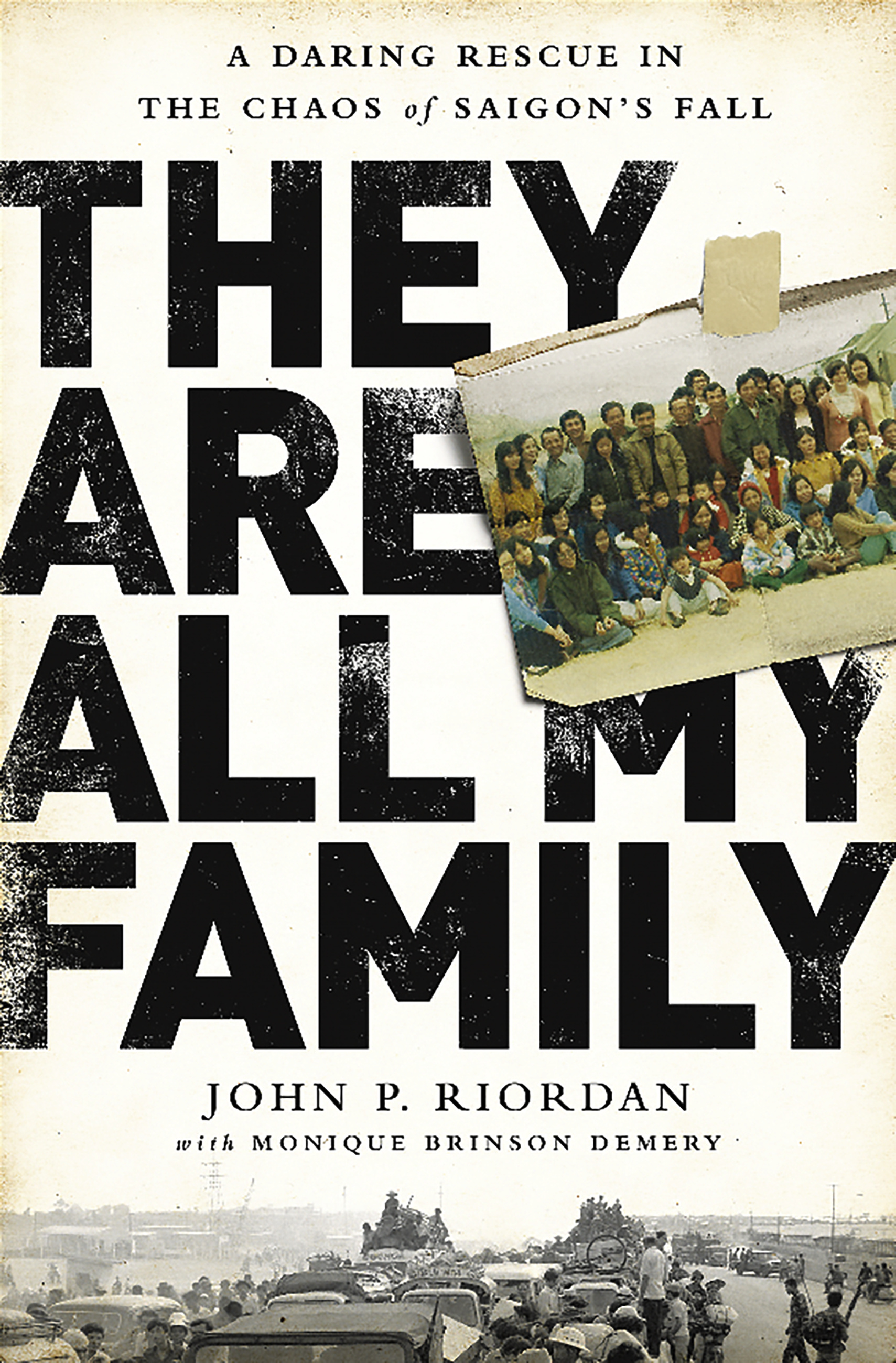

They Are All My Family

A Daring Rescue in the Chaos of Saigon's Fall

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 7, 2015

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610395038

Price

$36.00Price

$46.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 7, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Riordan — who had served in the US Army after the Tet Offensive and had left the military behind for a career in international banking — was not the type to take dramatic action, but once the North Vietnamese Army closed in on Saigon in April 1975 and it was clear that Riordan’s Vietnamese colleagues and their families would be stranded in a city teetering on total collapse, he knew he could not leave them behind. Defying the objections of his superiors and going against the official policy of the United States, Riordan went back into Saigon to save them.

In fifteen harrowing trips to Saigon’s airport, he maneuvered through the bureaucratic shambles, claiming that the Vietnamese were his wife and scores of children. It was a ruse that, at times, veered close to failure, yet against all odds, the improbable plan succeeded. At great risk, the Vietnamese left their lives behind to start anew in the United States, and now John is known to his grateful Vietnamese colleagues and hundreds of their American descendants as Papa.

They Are All My Family is a vivid narrative of one man’s ingenious strategy which transformed a time of enormous peril into a display of extraordinary courage. Reflecting on those fateful days in this account, John Riordan’s modest heroism provides a striking contrast to America’s ignominious retreat from the decade of conflict.

-

"A nail-biting account of one man's quiet heroism in the face of impossible odds."-Kirkus Reviews

“The book provides lots of details, replete with lots of reconstructed quotes, of Riordan's against-the-odds mission. And it has a string of happy endings—a rare and good thing for a book about the American war in Vietnam.”-VVA Veteran

"John Riordan is a quiet, gentle man who defied his bosses and in many ways his own nature when he rescued 106 of his Vietnamese colleagues and their families in the closing days of South Vietnam's collapse. He did it in a plot so devious and ingenious, I doubt even Graham Greene could have thought it up. Now he is telling the story in a book masterfully written with verve and heart. So hats off to John Riordan for his astonishing act of derring-do and for writing a great book." -Lesley Stahl, correspondent for 60 Minutes

"John Riordan has provided a moving testament to the redeeming power of human decency even in one of the darkest chapters of American history. Bravo for what he accomplished and for this riveting book." -Craig R. Whitney, former Vietnam bureau chief of The New York Times

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use