By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

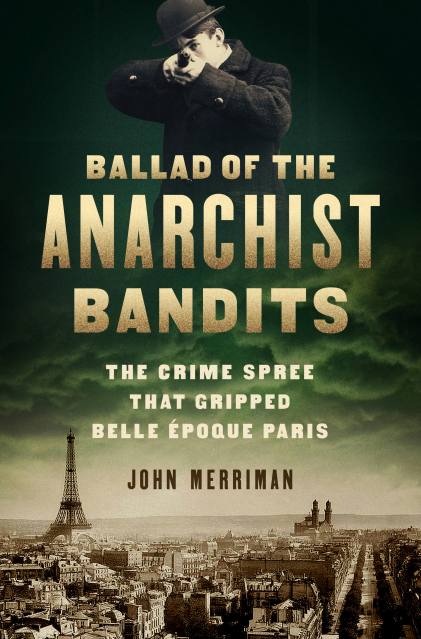

Ballad of the Anarchist Bandits

The Crime Spree that Gripped Belle Epoque Paris

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 3, 2017

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568589893

Price

$16.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $20.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 3, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

For six terrifying months in 1911-1912, the citizens of Paris were gripped by a violent crime streak. A group of bandits went on a rampage throughout the city and its suburbs, robbing banks and wealthy Parisians, killing anyone who got in their way, and always managing to stay one step ahead of the police. But Jules Bonnot and the Bonnot Gang weren’t just ordinary criminals; they were anarchists, motivated by the rampant inequality and poverty in Paris.

John Merriman tells this story through the eyes of two young, idealistic lovers: Victor Kibaltchiche (later the famed Russian revolutionary and writer Victor Serge) and Rirette Maîejean, who chronicled the Bonnot crime spree in the radical newspaper L’Anarchie. While wealthy Parisians frequented restaurants on the Champs-Ã?ysé, attended performances at the magnificent new opera house, and enjoyed the decadence of the so-called Belle Ã?oque, Victor, Rirette, and their friends occupied a vast sprawl of dank apartments, bleak canals, and smoky factories. Victor and Rirette rejected the violence of Bonnot and his cronies, but to the police it made no difference. Victor was imprisoned for years for his anarchist beliefs, Bonnot was hunted down and shot dead, and his fellow bandits were sentenced to death by guillotine or lifelong imprisonment.

Fast-paced and gripping, Ballad of the Anarchist Bandits is a tale of idealists and lost causes–and a vivid evocation of Paris in the dizzying years before the horrors of World War I were unleashed.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use