Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

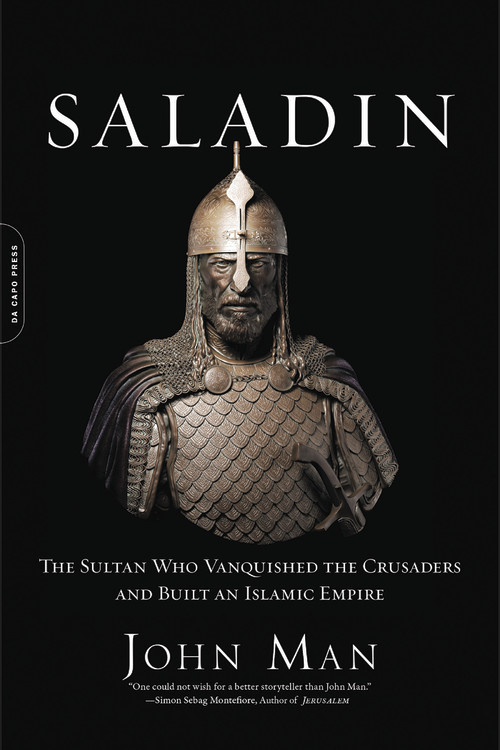

Saladin

The Sultan Who Vanquished the Crusaders and Built an Islamic Empire

Contributors

By John Man

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 28, 2017

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306825422

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Hardcover $26.99 $34.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 28, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Saladin remains one of the most iconic figures of his age. As the man who united the Arabs and saved Islam from Christian crusaders in the twelfth century, he is the Islamic world’s preeminent hero. A ruthless defender of his faith and brilliant leader, he also possessed qualities that won admiration from his Christian foes.

But Saladin is far more than a historical hero. Builder, literary patron, and theologian, he is a man for all times, and a symbol of hope for an Arab world once again divided. Centuries after his death, in cities from Damascus to Cairo and beyond, to the Arabian Peninsula and the Gulf, Saladin continues to be an immensely potent symbol of religious and military resistance to the West. He is central to Arab memories, sensibilities, and the ideal of a unified Islamic state.

John Man charts Saladin’s rise to power, his struggle to unify the warring factions of his faith, and his battles to retake Jerusalem and expel Christian influence from Arab lands. Saladin explores the life and enduring legacy of this champion of Islam while examining his significance for the world today.

Genre:

-

"One could not wish for a better storyteller than John Man."--Simon Sebag Montefiore, author of Jerusalem

-

"A tale about the life of a man and the passions that drove him"--Roanoke Times

-

"A worthy biography of an important Muslim hero"--Foreword Reviews

-

"Superb and eminently readable"--Chicago Tribune's Printers Row

-

"[A] masterful biography...The book tells a clear, vivid story of seemingly endless conflict, showing the strengths and weaknesses of both Christians and Muslims. The characters are fascinating...Man's style and pacing are just right for the general reader. This account provides valuable perspective for the twenty-first century tensions between Islam and the West."Internet Review of Books, 9/29/16

-

"An excellent overview on this complex man and his time."Military Periscope

-

"A very interesting and informative biography that provides insights relevant to issues surrounding the Middle East today."Toy Soldier & Model Figure

-

"The author of this book is an entertaining storyteller with an ear for a good turn of phrase."The Historian

-

"Man presents a complete biographical account of Saladin's life, while also building his narrative around the Crusades...Saladin can also be characterized as a contribution to the popular history of the Crusades...This volume...succeeds in presenting a vivid picture of medieval life in the Middle East that will appeal to a popular audience."H-Net