By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

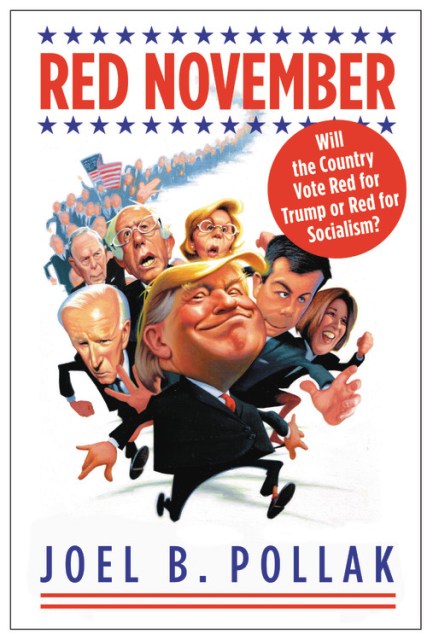

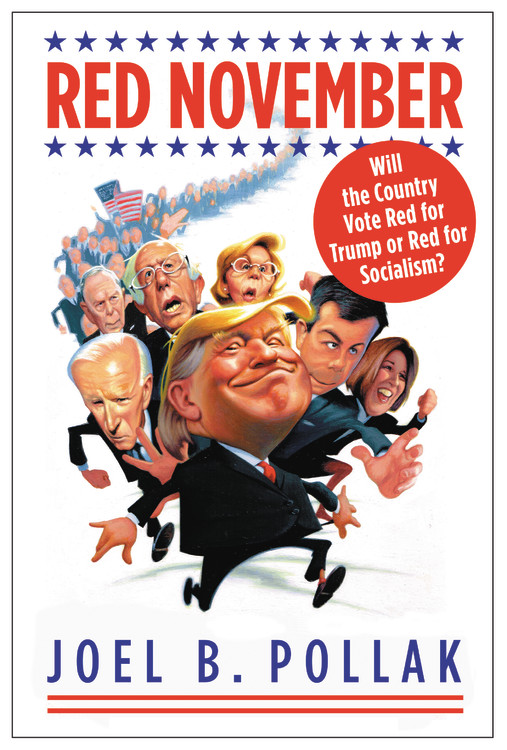

Red November

Will the Country Vote Red for Trump or Red for Socialism?

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 14, 2020

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781546099840

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 14, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A conservative journalist goes behind enemy lines to cover the 2020 Democratic primaries from the inside.

The 2020 Democratic primaries were some of the most extreme in the history of the United States. But the show isn’t over yet. Socialism is still on the rise, and ideas that used to be considered crazy are now even more mainstream than they were before.

In Red November, conservative journalist Joel Pollak tells the story of how the Democratic party got so extreme, and give a riveting account of life on the campaign trail. There are stories from the Democratic debates, interviews with candidates, and scuffles between journalists.

Part travelogue, part satire, part memoir, Red November is a factual, yet humorous, look behind-the-scenes at the candidates, activists, and voters as Democrats choose who will take on the sacred task of removing Donald Trump — “45,” as he is known to his haters — from the White House and ushering in a utopian age of “Medicare for All” and the “Green New Deal.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use