By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

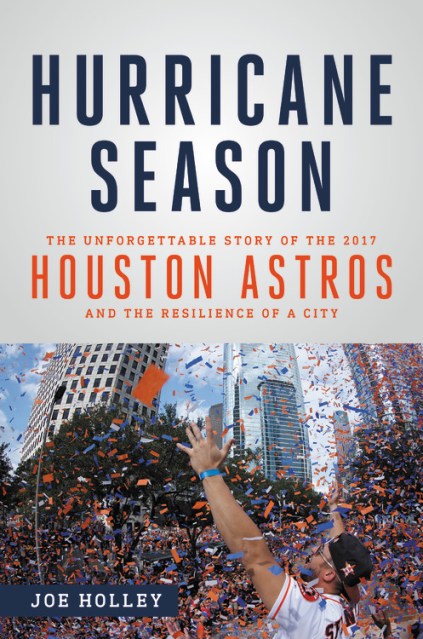

Hurricane Season

The Unforgettable Story of the 2017 Houston Astros and the Resilience of a City

Contributors

By Joe Holley

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 1, 2018

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316485241

Price

$36.00Price

$46.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.98

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 1, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

On November 1, 2017, the Houston Astros defeated the Los Angeles Dodgers in an epic seven game battle to become 2017 World Series champs. For the Astros, the combination of a magnificently played series, a 101-victory season, and the devastation Hurricane Harvey brought to their city was so incredible it might give Hollywood screenwriters pause. The nation’s fourth-largest city, still reeling in the wake of disaster, was smiling again.

The Astros’ first-ever World Series victory is a great baseball story, but it’s also the story of a major American city — a city (and a state) that the rest of the nation doesn’t always love or understand–becoming a sentimental favorite because of its grace and good will in response to the largest natural disaster in American history.

The Astros’ miracle season is also the fascinating tale of a thoroughly modern team. Constructed by NASA-inspired analytics, the team’s data-driven system took the game to a more sophisticated level than the so-called Moneyball approach. The team’s new owner, Jim Crane, bought into the system and was willing to endure humiliating seasons in the baseball wilderness with the hope, shared by few initially, that success comes to those who wait. And he was right.

But no data-crunching could take credit for a team of likeable, refreshingly good-natured young men who wore “Houston Strong” patches on their jerseys and meant it–guys like shortstop Carlos Correa, who kept a photo in his locker of a Houston woman trudging through fetid water up to her knees. The Astros foundation included George Springer, a powerful slugger and rangy outfielder; third-baseman Alex Bregman, whose defensive play and clutch hitting were crucial in the series; and, of course, the stubby and tenacious second baseman Jose Altuve, the heart and soul of the team.

Hurricane Season is Houston Chronicle columnist Joe Holley’s moving account of this extraordinary team–and the extraordinary circumstances of their championship.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use