By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

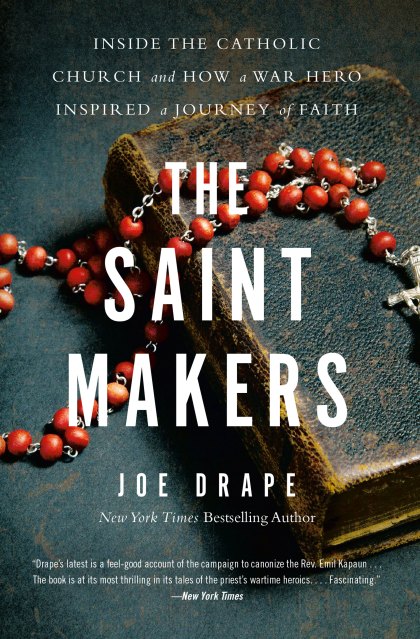

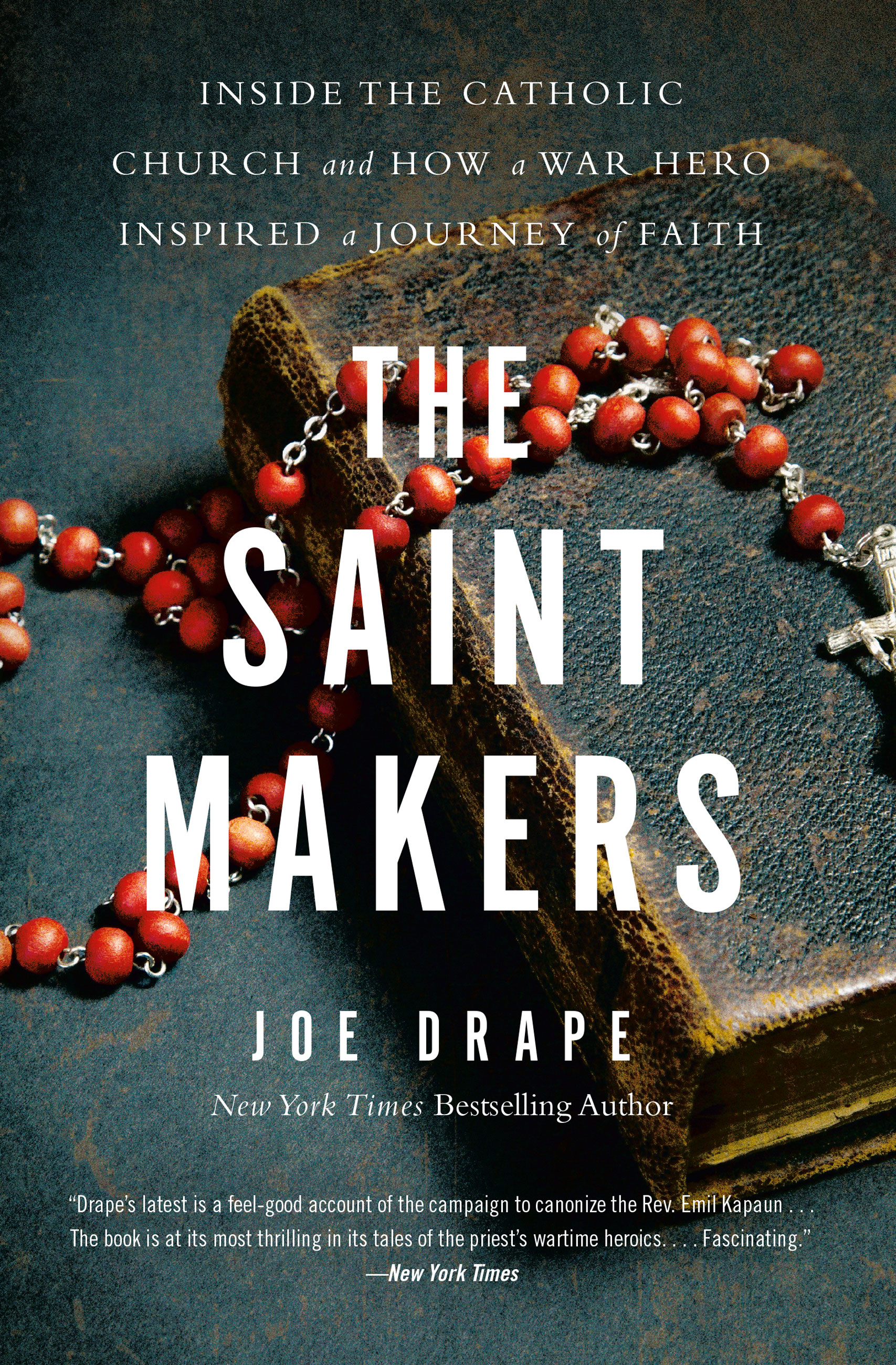

The Saint Makers

Inside the Catholic Church and How a War Hero Inspired a Journey of Faith

Contributors

By Joe Drape

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 1, 2020

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316268806

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 1, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Part biography of a wartime adventurer, part detective story, and part faith journey, this intriguing book from a New York Times journalist and bestselling author takes us inside the modern-day making of a saint.

The Saint Makers chronicles the unlikely alliance between Father Hotze and Dr. Andrea Ambrosi, a country priest and a cosmopolitan Italian canon lawyer, as the two piece together the life of a long dead Korean War hero and military chaplain and fashion it into a case for eternal divinity. Joe Drape offers a front row seat to the Catholic Church's saint-making machinery—which, in many ways, has changed little in two thousand years-and examines how, or if, faith and science can co-exist.

This rich and unique narrative leads from the plains of Kansas to the opulent halls of the Vatican, through brutal Korean War prison camps, and into the stories of two individuals, Avery Gerleman and Chase Kear, whose lives were threatened by illness and injury and whose family and friends prayed to Father Kapaun, sparking miraculous recoveries in the heart of America. Gerleman is now a nurse, and Kear works as a mechanic in the aerospace industry. Both remain devoted to Father Kapaun, whose opportunity for sainthood relies in their belief and medical charts. At a time when the church has faced severe scandal and damage, and the world is at the mercy of a pandemic, this is an uplifting story about a priest who continues to an example of goodness and faith.

Ultimately, The Saint Makers is the story of a journey of faith—for two priests separated by seventy years, for the two young athletes who were miraculously brought back to life with (or without) the intercession of the divine, as well as for readers—and the author—trying to understand and accept what makes a person truly worthy of the Congregation of Saints in the eyes of the Catholic Church.

The Saint Makers chronicles the unlikely alliance between Father Hotze and Dr. Andrea Ambrosi, a country priest and a cosmopolitan Italian canon lawyer, as the two piece together the life of a long dead Korean War hero and military chaplain and fashion it into a case for eternal divinity. Joe Drape offers a front row seat to the Catholic Church's saint-making machinery—which, in many ways, has changed little in two thousand years-and examines how, or if, faith and science can co-exist.

This rich and unique narrative leads from the plains of Kansas to the opulent halls of the Vatican, through brutal Korean War prison camps, and into the stories of two individuals, Avery Gerleman and Chase Kear, whose lives were threatened by illness and injury and whose family and friends prayed to Father Kapaun, sparking miraculous recoveries in the heart of America. Gerleman is now a nurse, and Kear works as a mechanic in the aerospace industry. Both remain devoted to Father Kapaun, whose opportunity for sainthood relies in their belief and medical charts. At a time when the church has faced severe scandal and damage, and the world is at the mercy of a pandemic, this is an uplifting story about a priest who continues to an example of goodness and faith.

Ultimately, The Saint Makers is the story of a journey of faith—for two priests separated by seventy years, for the two young athletes who were miraculously brought back to life with (or without) the intercession of the divine, as well as for readers—and the author—trying to understand and accept what makes a person truly worthy of the Congregation of Saints in the eyes of the Catholic Church.

-

“Drape’s latest is a feel-good account of the campaign to canonize the Rev. Emil Kapaun...The book is at its most thrilling in its tales of the priest’s wartime heroics....Fascinating.”The New York Times

-

"Inspiring, and beautifully written, Joe Drape's new book seamlessly combines three fascinating tales: the saga of a Catholic war hero and future saint, the story of how the church 'canonizes' a person (that is, recognizes saints) and the spiritual journey of an initially skeptical author. The Saint Makers is revelatory in truest sense of the word: it reveals Father Kapaun's astounding holiness, the church's dogged pursuit of the truth, and the author's heartfelt quest for a more authentic spiritual life."James Martin, SJ, author of My Life with the Saints and Learning to Pray

-

"In a riveting story that moves from a small town in Kansas to the halls of the Vatican, Joe Drape draws back the curtain on one of Catholicism's least-understood processes, the making of a saint. It's a story of spiritual struggle -- in prisoner-of-war-camps in Korea, in the lives of modern families praying for miraculous healing, and in the personal pilgrimage of an author alienated by scandals in the church. Drape's narrative is engaging and thought-provoking. With a combination of journalistic skepticism and religious sensitivity, he confronts the question: Why do saints matter today?"John Thavis, author of The Vatican Diaries

-

“A phenomenal book…[Joe Drape] is a fantastic writer….He takes you through this incredible journey of an American war hero who was a Catholic priest who was so brave and patient and peaceful and kind and had so much valor and humanity.”“Kennedy Saves the World,” Fox News

-

“Hope and inspiration seem in short supply as this pandemic persists, but a bit of divine intervention seems to burst from Drape’s new book… Resisting hagiography, he investigates the convoluted process of saint-making and the fascinating characters who gather evidence and led the campaign for Father Kapuan’s sainthood. Drape enriches an inquiry into his own faith with a light personal touch, drawing on his Jesuit youth and reflecting the universal draw of Kapaun’s heroism.”The National Book Review

-

"Engaging... this profile in sainthood is humane and compelling."Kirkus Reviews

-

“An illuminating exploration of the heroism of Korean War military chaplain Emil Kapaun….[A]moving account of courage and faith in the killing fields of Korea.”Publishers Weekly

-

“An absorbing story….Drape… thoughtfully explor[es] his complex relationship with his faith, burnished by his research into Fr. Kapaun…. This insightful account will appeal to readers who enjoy stories about faith and war heroics, and those interested in saint making within the Catholic Church.”Library Journal

-

"A fascinating look into a world that for centuries has been mostly hidden.... Drape [tells] the story of the saint making process, with detail and drama...[an] extraordinary look into the previously unknown and most holy process of the Catholic Church.""Feisty Side of Fifty" podcast

-

"A fantastic read."KSCJ’s “Having Read That…”

-

“Joe Drape tells a compelling tale in The Saint Makers. Indeed, the man is a fantastic writer, and his talent is on full display….Here the book will likely prove eye-opening for the average Catholic who is unfamiliar with what it takes to get someone beatified or canonized….Drape is on a pilgrimage. Judging by what he writes here, he is growing in his faith, and his recounting of his journey is compelling, thought-provoking reading.”National Catholic Register

-

"A great book."“The Miracle Hunter” (EWTN Catholic Radio)

-

“The Saint Makers is both insightful and refreshing….What makes this story unique is the multilayered approach of storytelling in The Saint Makers that makes a complex story accessible to those who have no prior knowledge of Japan, the Korean War, the Catholic Church, or the miracles needed to obtain Sainthood.”KRPS

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use