By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

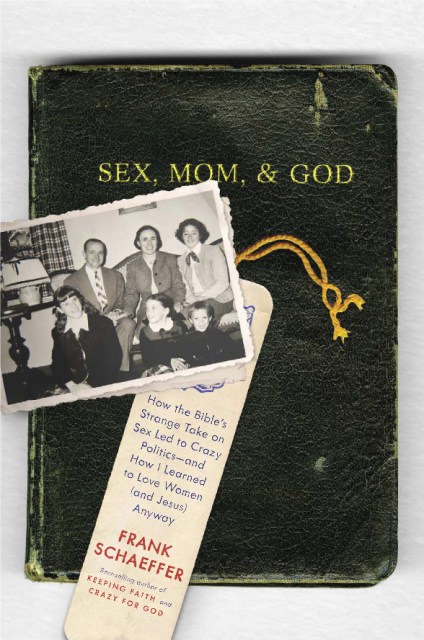

Sex, Mom, and God

How the Bibles Strange Take on Sex Led to Crazy Politics -- and How I Learned to Love Women (and Jesus) Anyway

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 31, 2011

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780306819858

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 31, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“Mom was a much nicer person than her God. There are many biblical regulations about everything from beard-trimming to menstruating. Mom worked diligently to recast her personal-hygiene-obsessed God in the best light.”

Alternating between laugh-out-loud scenes from his childhood and acidic ruminations on the present state of an America he and his famous fundamentalist parents helped create, bestselling author Frank Schaeffer asks what the Glenn Becks and the Rush Limbaughs and the paranoid fantasies of the “right-wing echo chamber” are really all about.

Here’s a hint: sex.

The unforgettable central character in Sex, Mom, and God is the author’s far-from-prudish evangelical mother, Edith, who sweetly but bizarrely provides startling juxtapositions of the religious and the sensual thoughout Schaeffer’s childhood. She was, says Frank Schaeffer, “the greatest illustration of the Divine beauty of Paradox I’ve encountered . . . a fundamentalist living a double life as a lover of beauty who broke all her own judgmental rules in favor of creativity.”

Charlotte Gordon, the award-winning author of Mistress Bradstreet, calls Sex, Mom, and God “a tour de force . . . Sarah Palin, ‘The Family,’ Anne Hutchinson, adultery, abortion, homophobia, Uganda, Ronald Reagan, B. B. King, Billy Graham, Hugh Hefner — it’s all here. This is the kind of book I did not want to end.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use