Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

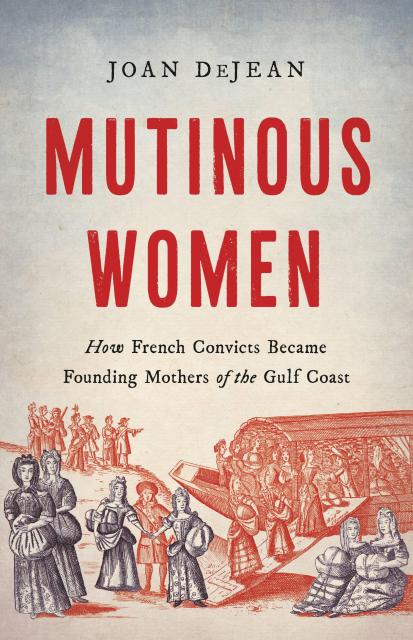

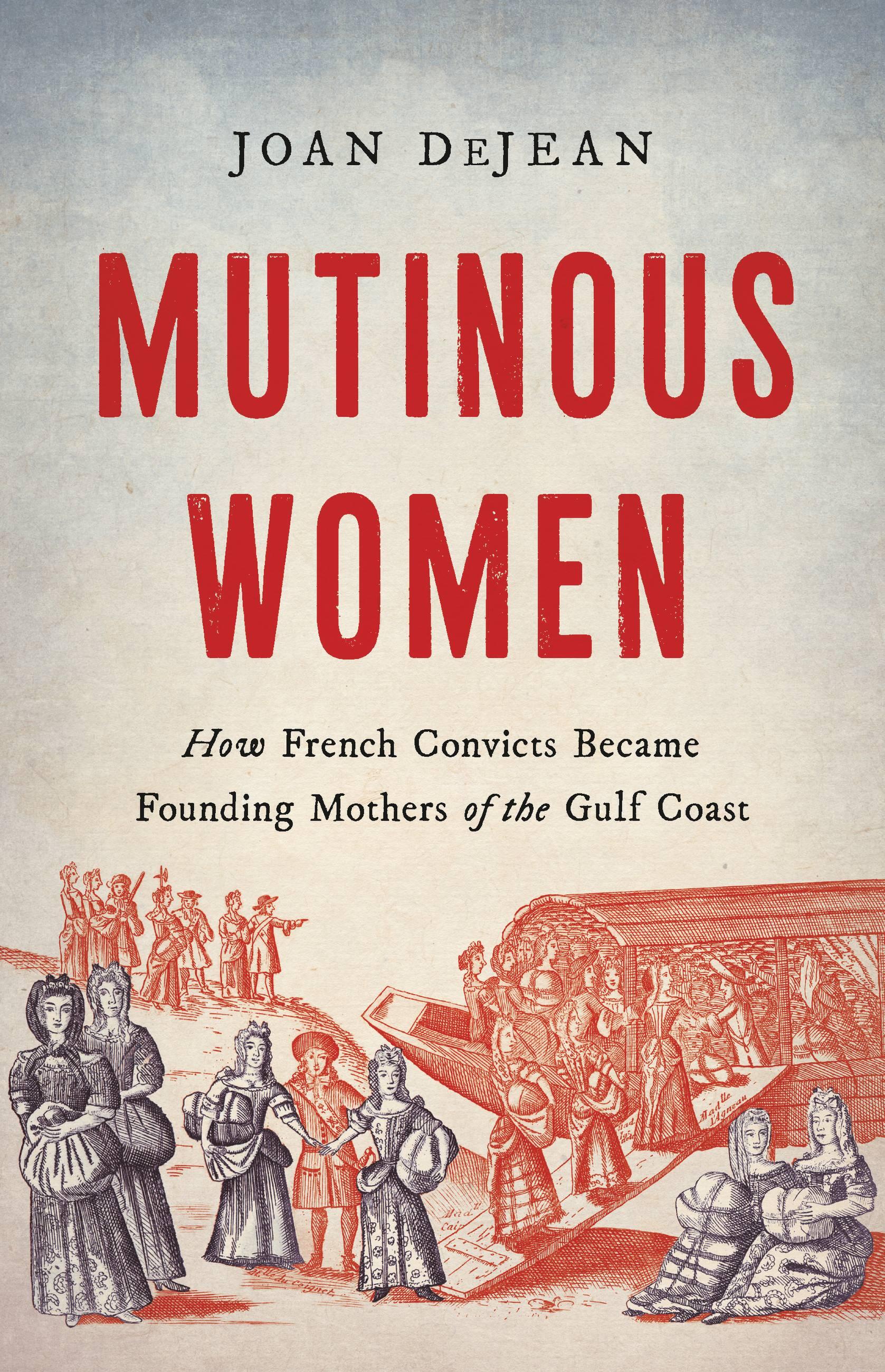

Mutinous Women

How French Convicts Became Founding Mothers of the Gulf Coast

Contributors

By Joan DeJean

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 19, 2022

- Page Count

- 448 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541600591

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Hardcover $35.00 $46.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 19, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The secret history of the rebellious Frenchwomen who were exiled to colonial Louisiana and found power in the Mississippi Valley

In 1719, a ship named La Mutine (the mutinous woman), sailed from the French port of Le Havre, bound for the Mississippi. It was loaded with urgently needed goods for the fledgling French colony, but its principal commodity was a new kind of export: women.

Falsely accused of sex crimes, these women were prisoners, shackled in the ship’s hold. Of the 132 women who were sent this way, only 62 survived. But these women carved out a place for themselves in the colonies that would have been impossible in France, making advantageous marriages and accumulating property. Many were instrumental in the building of New Orleans and in settling Louisiana, Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, and Mississippi.

Drawing on an impressive range of sources to restore the voices of these women to the historical record, Mutinous Women introduces us to the Gulf South’s Founding Mothers.

-

Recipient of the Louis Gottschalk Prize

-

“Gripping from its opening scene of a corpse discovered on a Paris side street, Joan DeJean’s Mutinous Women tells the stories of these French women, deported as unwanted criminals to what would become, less than a century later, part of the United States… Through astounding research in French and Louisiana archives… Ms. DeJean uses her knowledge as a scholar of early modern France to great effect. … a fascinating history and a reminder that all kinds of people helped to build what became the United States.”Wall Street Journal

-

“Working with a chaotic and often confusing historical record, DeJean traces the constellation of forces—including avarice, corruption and misogyny—that permitted the rapid roundup of another 96 or so female prisoners to be transported in the dank hold of La Mutine. The horrific conditions of the women’s journey and the will to survive that must have sustained them when they were set down, largely without resources, in a barren, swampy, inhospitable land, are evoked in vivid detail.”New York Times Book Review

-

“Their lives became early examples of the American dream, and of its violence… In their previously little-known stories is a concise picture of all that makes U.S. history remarkable and troubling.”The Atlantic

-

“An array of impressive primary sources… guide the overarching theme of this groundbreaking study, revealing the importance of these women in the early years of French colonization of the Third Coast.”CHOICE

-

"What transpired after they landed ashore, however, is a clear demonstration of the beauty and power of the feminine spirit, and DeJean chronicles their experiences in well-written, often gripping prose....Readers will come away fascinated and inspired by this relatively unknown tale of strength and the human spirit."Kirkus (starred review)

-

“DeJean skillfully reads between the lines of the existing police and prison documentation to bring context and nuance to these women’s stories…. This scrupulous account restores a group of remarkable women to their rightful place in French and American history.”Publishers Weekly

-

“Exploitation and dishonesty fueled the settling of the Gulf Coast, and so doing rendered these women voiceless for generations. With rich writing, author and University of Pennsylvania professor DeJean gives the women who settled Louisiana, and their lost stories, a long-overdue historical reckoning.”Booklist

-

“DeJean… does a wonderful job of tracing the lives of these women through government and parish records, plotting their marriages, deaths, births and financial fortunes through succeeding decades. … A fascinating book for history lovers, not just academics.”Library Journal

-

“Joan DeJean has written a gripping narrative of female courage and resilience that gives the women of La Mutine a justice long denied. Their astonishing and all-but-forgotten story will now take its rightful place in our rapidly changing understanding of the nature and meaning of European settlement of the New World.”Drew Faust, Arthur Kingsley Porter University Professor and president emerita, Harvard

-

“This is a wonderful book, richly detailed, meticulously researched, and beautifully written. Telling the hitherto unknown story of a group of working-class, young women unjustly seized by authorities from the streets of early eighteenth-century Paris, Mutinous Women takes us on a fascinating journey from the poorer quarters of the vast city to the emerging towns and expansive landscapes of French Louisiana. Against all odds, after enduring terrible privations in their homeland and a long Atlantic crossing chained together in the hold of the frigate La Mutine, most of the women who survived succeeded in establishing their own families and eventually achieved a level of material comfort their native country denied them. Joan DeJean's account offers eloquent testimony to the courage and fortitude of these brave young women who played a significant role in the founding of French Louisiana.”James Horn, author of A Brave and Cunning Prince

-

“Mutinous Women brings to life a remarkable story, that of some two hundred women arbitrarily deported from France to the fledgling colony of Louisiana in 1719. Many died crossing the ocean, but others survived to play crucial roles in the settlement of a region that still treasures its French heritage. Joan DeJean’s vivid narrative is both an engrossing addition to the history of American colonization and a testimony to the resilience of the human spirit.”Jeremy Popkin, author of A New World Begins: The History of the French Revolution

-

“In a work of archival virtuosity and daring reconstruction, Joan DeJean takes us from the villages of France to the alleys of Paris to the bayous of Louisiana, recovering the lives of a group of women heretofore lost to history. Exquisitely vulnerable to the capricious forces of ambition, finance, and venality, these indomitable women wrested control of their lives to chart new paths for themselves and their descendants.”François Furstenberg, professor of history, Johns Hopkins University