Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

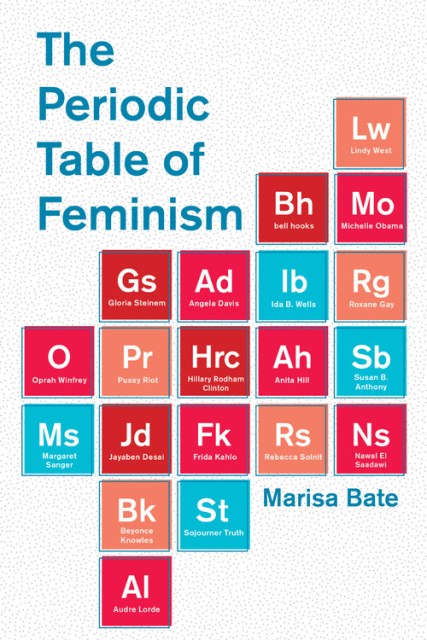

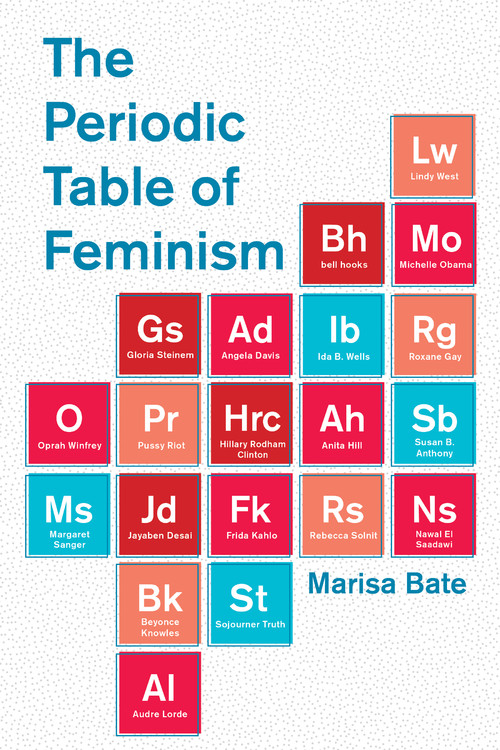

The Periodic Table of Feminism

Contributors

By Marisa Bate

Formats and Prices

Price

$20.00Price

$26.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $20.00 $26.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 16, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A quirky, intelligent, and stylish review of the feminist movement, told through the stories of standout figures who have shaped it, The Periodic Table of Feminism charts the impact of female leaders from Betty Friedan and Ruth Bader Ginsburg to Michelle Obama and Oprah.

Using the periodic table as a categorical device, the featured women are divided into “chemical” groups to show how the women and the battles they fought speak to each other across time and geography:

Precious Metals: the face of the movements, like Simone De Beauvoir and Gloria Steinem

Catalysts: Pioneers and fire-starters, like Susan B. Anthony and Sheryl Sandberg

Conductors: The organizers, like Sojourner Truth and Rebecca Solnit

Diatomics: Women working together, like The Spice Girls and The Women’s Equality Party

Stabilizers: Pacifists, like Margaret Atwood, Lindy West, and Eve Ensler

Explosives: Radicals, anarchists, and violent uprisers, like Adrienne Rich and Roxane Gay

Rejectors: “I am not a feminist” proclaimers, like Alice Walker and Sarah Jessica Parker

With clever “top 10” lists — such as Feminists in Fiction, Feminists Before Feminism, Best Women’s Marches, and Male Feminists — plus 120 meme-ready illustrations and inspiring pull quotes, this essential guide to feminism offers courage and inspiration for a new generation.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 16, 2018

- Page Count

- 208 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580058681

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use