Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

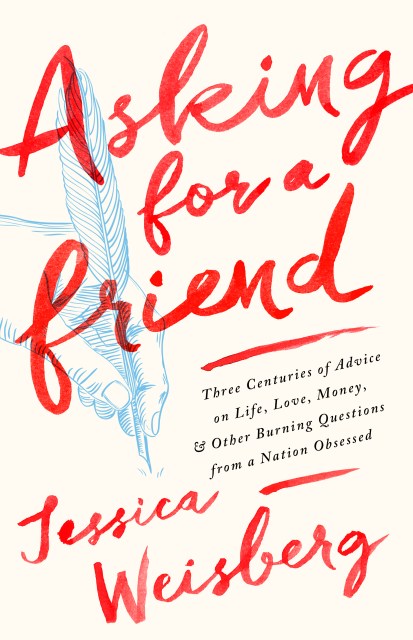

Asking for a Friend

Three Centuries of Advice on Life, Love, Money, and Other Burning Questions from a Nation Obsessed

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Hardcover $37.00 $47.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 3, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Americans, for all our talk of pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps, obsessively seek advice on matters large and small. Perhaps precisely because we believe in bettering ourselves and our circumstances in life, we ask for guidance constantly. And this has been true since our nation’s earliest days: from the colonial era on, there have always been people eager to step up and offer advice, some of it lousy, some of it thoughtful, but all of it read and debated by generations of Americans.

Jessica Weisberg takes readers on a tour of the advice-givers who have made their names, and sometimes their fortunes, by telling Americans what to do. You probably don’t want to follow all the advice they proffered. Eating graham crackers will not make you a better person, and wearing blue to work won’t guarantee a promotion. But for all that has changed in American life, it’s a comfort to know that our hang-ups, fears, and hopes have not. We’ve always loved seeking advice — so long as it’s anonymous, and as long as it’s clear that we’re not asking for ourselves; we’re just asking for a friend.

Genre:

-

"Take my advice and read this fascinating book immediately. It's the only piece of advice I can offer that even begins to compare to the advice of the writers it chronicles. Whether it's Benjamin Franklin, Dr. Spock, or 'The King of Quora,' Jessica Weisberg captures her subjects' work and personalities with engaging insight. As she does so, she also offers an illuminating look into what society craves advice on in any given age (from retaining your job in the 1930s to retaining your marriage in the 1990s). It's a must read for anyone who loves learning about history and human angst, as well as those who love their local paper's advice column."Jennifer Wright, author of It Ended Badly: 13 of the Worst Breakups in History

-

"Rich with insight and surprising facts, Jessica Weisberg's ingenious appraisal of America's guidance-givers doubles as a wholly unexpected history of our national psyche. At long last, the lowly advice column gets its due!"Kate Bolick, author of Spinster: Making a Life of One's Own

-

"An oddly soothing antidote to the millenarian terrors of today, Jessica Weisberg's history of ordinary American anxiety is as warm, funny, entertaining, and chattily insightful as the advice-dispensers she portrays. In the centuries before the internet, these were the ones we turned to with questions so obscure, embarrassing, weird, or mortifyingly personal that only a stranger would do."Larissa MacFarquhar, authorof Strangers Drowning: ImpossibleIdealism, Drastic Choices, and the Urge to Help

-

"Jessica Weisberg's hilarious, enlightening odyssey through the history of advice columns chronicles the evolution of our anxieties over how to act. However weird or offensive some of our questions have been, it's heartening to know that at least we've always been trying. A surprising and delightful read."Mac McClelland, author of Irritable Hearts: A PTSD Love Story

-

"Welcome to a hilarious dinner party of outrageous characters! Each one of Weisberg's profiles is like a witty, surprisingly profound toast. I can't stop talking about this book to everyone I know; it snuck up on me as one of the most insightful books about human nature that I've ever read."Courtney E.Martin, author of The New Better Off:Reinventing the American Dream

- On Sale

- Apr 3, 2018

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568585352

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use