By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

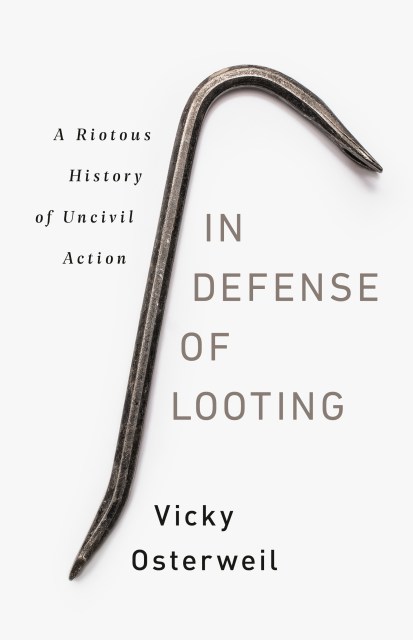

In Defense of Looting

A Riotous History of Uncivil Action

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 25, 2020

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781645036692

Price

$30.00Price

$40.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $40.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 25, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Looting — a crowd of people publicly, openly, and directly seizing goods — is one of the more extreme actions that can take place in the midst of social unrest. Even self-identified radicals distance themselves from looters, fearing that violent tactics reflect badly on the broader movement.

But Vicky Osterweil argues that stealing goods and destroying property are direct, pragmatic strategies of wealth redistribution and improving life for the working class — not to mention the brazen messages these methods send to the police and the state. All our beliefs about the innate righteousness of property and ownership, Osterweil explains, are built on the history of anti-Black, anti-Indigenous oppression.

From slave revolts to labor strikes to the modern-day movements for climate change, Black lives, and police abolition, Osterweil makes a convincing case for rioting and looting as weapons that bludgeon the status quo while uplifting the poor and marginalized. In Defense of Looting is a history of violent protest sparking social change, a compelling reframing of revolutionary activism, and a practical vision for a dramatically restructured society.

Genre:

-

"Osterweil debuts with a provocative, Marxist-informed defense of looting as a radical and effective protest tactic...a bracing rethink of the goals and methods of protest."Publishers Weekly

-

"A reflection on violence as a form of social protest that can lead to social change."New York Journal of Books

-

"[In Defense of Looting] is as much an argument for the possibilities of a riot as it is a reckoning between history as it happens and history as it is read.... [Osterweil's] readings of history lend the book its exhilarating quality and make anything seem possible."Frieze

-

"In Defense of Looting is a clear and damning indictment of the origins and evolution of property rights, race, and policing in the United States. Ultimately, Osterweil demands we not only overcome the respectability politics animating our desire for 'peaceful protests,' but that we ambitiously work to abolish the racial capitalist logics at the heart of American empire."Zoé Samudzi, coauthor of As Black As Resistance

-

"In engaging and accessible prose, Vicky Osterweil lays out an intellectual defense of looting that is as thorough and compelling as it is necessary and revolutionary. The history here is alive and vital, and Osterweil's grasp of it pushes any reader who has doubted the legitimacy of looting as a political action to search deeply and reconsider their position."Mychal Denzel Smith, author of Stakes Is High: Life After the American Dream

-

"With the right ideas at the right time, Vicky Osterweil has given us a powerful tool for resistance in the 21st century. In Defense of Looting could change American politics forever."Malcolm Harris, author of Kids These Days: The Making of Millennials

-

"A passionate, in-depth study of one of history's most radical-and reviled-forms of direct action. In clear, precise prose, Osterweil lays bare the racialized settler-colonial roots of policing and property in the US, outlines the possibilities of militant resistance, and emphasizes the necessity of Black and Indigenous liberation. In Defense of Looting is a bracing and necessary read, written with great care and radical hope. As Osterweil herself says, 'The future is ours to take. We just need to loot it.'"Kim Kelly, labor columnist, Teen Vogue

-

"In this book the act of looting is the starting point for challenging the conventional beliefs around people, property, and justice. How we treat looting, whose acts are considered looting, and what is looted frame essential interventions in understanding uprising. The stakes are not of 'stuff,' TVs, and clothes; they're about ourselves and our communities. Whether at the policy level or in our personal daily politics, the historical insights and moral clarity of this book illuminate a way forward from the real crimes that structure our society."Ayesha A. Siddiqi, writer and emeritus editor-in-chief of The New Inquiry

-

“In Defense of Looting incisively explores the history of revolution, breaking down the myths that not only reinforce white supremacy, but also whitewash civil rights struggles and revolutionary acts, removing valuable tools from the arsenals of those who need them most…In Defense of Looting is not merely playing devil’s advocate or being provocative for the sake of being provocative, it is full-force challenging everyone to take a hard look at a hard subject, to stare slavery and injustice square in the eyes and not blink.”San Francisco Book Review

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use