By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

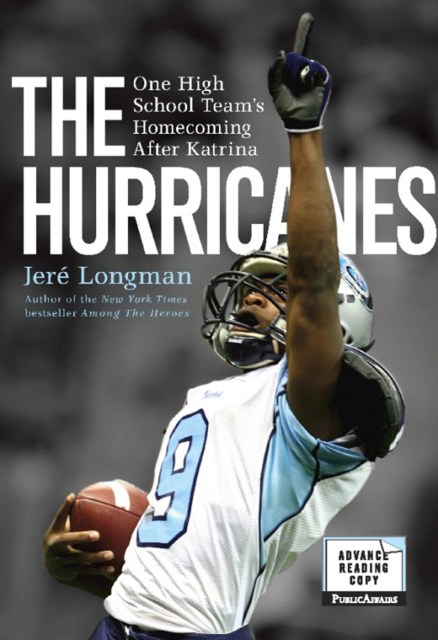

The Hurricanes

One High School Team's Homecoming After Katrina

Contributors

By Jere Longman

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 26, 2008

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786731640

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $17.99 $22.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 26, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina pummeled the lower end of Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, a peninsula housing one of the nation’s most isolated, vulnerable, and vital counties. A year later several ravaged communities came together to form South Plaquemines High. Kids who were former rivals defiantly nicknamed their football team the Hurricanes and made the 2006 state playoffs.

In 2007, South Plaquemines set its sights on a state championship. The Hurricanes used a trailer as a makeshift locker room and lifted weights in a destroyed gym that had no electricity. For the players, many of them still living in FEMA trailers, football offered a refuge.

Bestselling author Jer’ Longman spent two seasons following the team. In The Hurricanes, the team’s journey provides a lens through which to view the legacy of Katrina, the cycle of poverty in rural America, and the attempt to maintain traditions in the face of uncertainty. Football is a familiar remnant of the way things used to be — and a sign of hope in a place of disaster.

-

Biloxi Sun-Herald, July, 27, 2008

“A chill ran down my spine as I was reading the first chapter of "The Hurricanes," a story of high school football in south Louisiana in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.” Sports Illustrated , September 15, 2008

“The Hurricanes…is the richest, most engrossing treatment of high school football and community since Friday Night Lights.”

New York Times Book Review, September 7, 2008

“The losses and the struggle for revival [Longman] movingly examines take place in the real world of FEMA trailers and displaced families as much as in the artificial one of a football game.”New York Post, August 24, 2008

"The Hurricanes" is solidly reported, but it's a sports book at heart.”New Orleans Times-Picayune, October 18

“Longman combines a great sports story with a telling human saga…Longman knows the culture, and he beautifully spins his tale of sports triumph into something grander, a chronicle of Louisiana life, a plea to save the wetlands, an examination on the demands on these young men and their families in the wake of horrific disaster.”

-

Buzz Bissinger, author of Friday Night Lights and Three Nights in August

“Jeré Longman has written a book that is beautiful, poignant, and shows us all that sports can be, and so rarely is anymore, in our winning-at-all-costs culture. You will love The Hurricanes.”Neil Swidey, author of The Assist

“This captivating tale of struggle and triumph in post-Katrina Louisiana is ostensibly about football. But powered by Jeré Longman’s restless curiosity, it delivers so much more, taking readers from the gridiron to FEMA trailer parks and oyster grounds, and proving once again that big new stories really get interesting only after the packs of live-shot reporters have ridden their satellite trucks out of town.”Kevin Merida, associate editor of The Washington Post and editor of Being a Black Man: At the Corner of Progress and Peril

“Jeré Longman’s The Hurricanes is a riveting triumph. Written with exquisite detail, it has soul and verve and poignancy. Longman captures not only the human drama of a storm-displaced high school football team, but reminds us that the tragedies of Katrina live on. From the moment I started reading this book, I didn’t want to put it down.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use