By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

Unwanted Spy

The Persecution of an American Whistleblower

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 15, 2019

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568585581

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 15, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

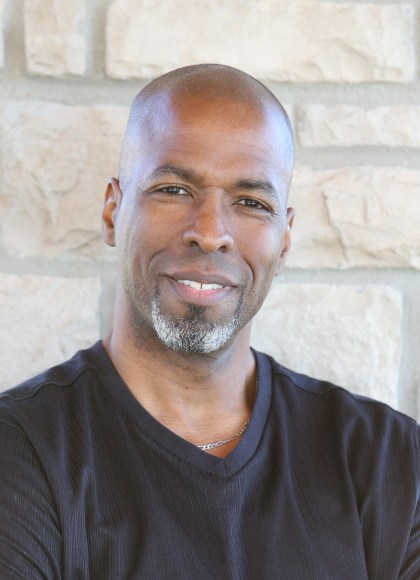

In 2015, Jeffrey Sterling was sentenced to prison, convicted of violating the Espionage Act. Sterling, it is now clear, was another victim of our government’s draconian crackdown on alleged leakers and whistleblowers.

Sterling grew up in a small, segregated town in Missouri and jumped at the chance to broaden his world and serve his country, first in law school and later in the CIA. After an impressive career, Sterling’s progress came to a sudden halt: he was denied opportunities because of his race and was pushed out of the Agency. Later, Sterling courageously blew the whistle on the CIA’s botched covert operation in Iran to Senate investigators. After a few quiet years in Missouri with his wife, he was arrested suddenly and charged with espionage.

Unwanted Spy is an inspiring account of one man’s uncompromising commitment to the truth and a reminder of the principles of justice and integrity that should define America.

-

"A book that amply demonstrates grave flaws in the criminal justice system."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Americans owe a debt to Jeffrey Sterling, who told the truth and endured imprisonment for us. His story is a powerful tale of integrity and bravery and the price a decent American paid for defending the values enshrined in the Bill of Rights. Make your children read it and learn."Charles Glass, former ABC News Chief Middle East Correspondent and author of They Fought Alone: The True Story of the Starr Brothers, British Secret Agents in Nazi-Occupied France

-

"Unwanted Spy is at the same time an American tragedy and a first-person account of how to live an upstanding life against daunting odds. Jeffrey Sterling is a patriot. He is also one of the most courageous and underappreciated whistleblowers in contemporary America. We all want to believe the best about our country, our government, and our society. But the truth is sometimes ugly. And sometimes patriots are harmed by that ugliness. Jeffrey Sterling was vilified by our government because he wouldn't toe the line. He paid for his conscientiousness with his freedom. Unwanted Spy makes it clear, though, that he was right and 'they' were wrong. He's the better man for it."John Kiriakou, former CIA counterterrorismofficer and senior investigator for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee

-

"[His] autobiography resonantly places his CIA experience in the context of epochal grievances concerning institutional racism."The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS–Americas)

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use