Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

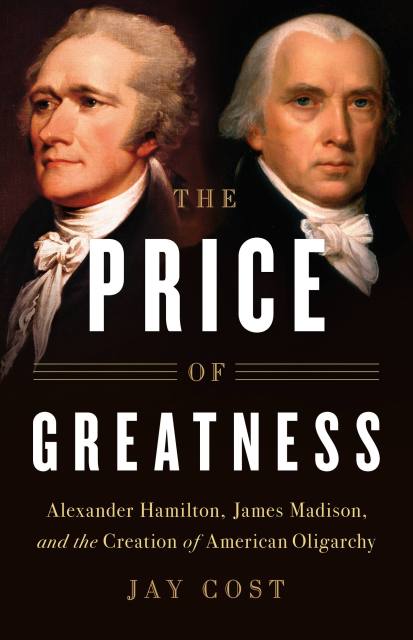

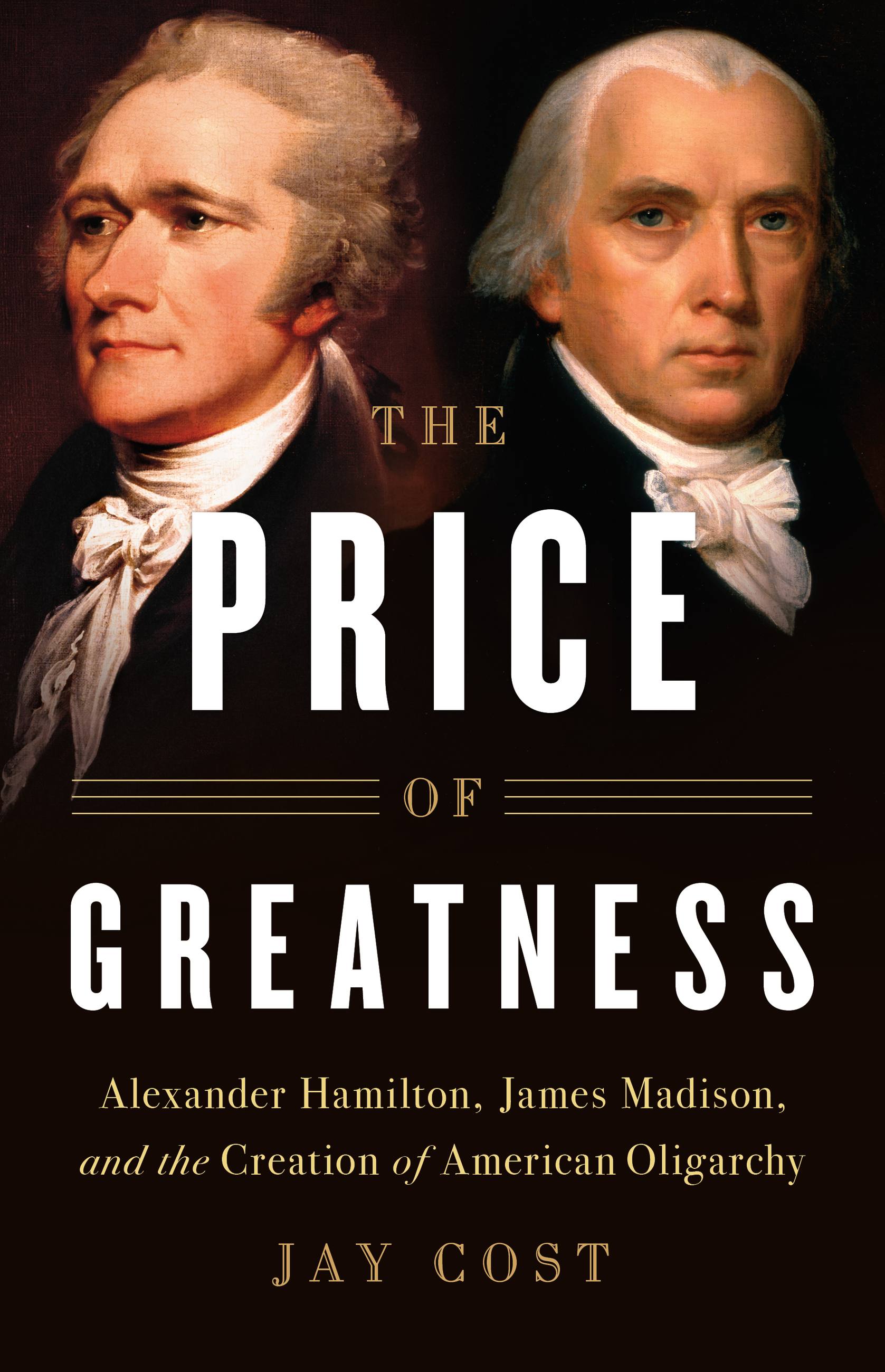

The Price of Greatness

Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and the Creation of American Oligarchy

Contributors

By Jay Cost

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 5, 2018

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541697485

Price

$16.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $20.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 5, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In the history of American politics there are few stories as enigmatic as that of Alexander Hamilton and James Madison’s bitterly personal falling out. Together they helped bring the Constitution into being, yet soon after the new republic was born they broke over the meaning of its founding document. Hamilton emphasized economic growth, Madison the importance of republican principles.

Jay Cost is the first to argue that both men were right — and that their quarrel reveals a fundamental paradox at the heart of the American experiment. He shows that each man in his own way came to accept corruption as a necessary cost of growth. The Price of Greatness reveals the trade-off that made the United States the richest nation in human history, and that continues to fracture our politics to this day.