By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

The Words That Made Us

America's Constitutional Conversation, 1760-1840

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 4, 2021

- Page Count

- 832 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465096350

Price

$40.00Price

$50.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $40.00 $50.00 CAD

- ebook $22.99 $29.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $44.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 4, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From a preeminent legal scholar, a “fascinating” and “masterful” (Wall Street Journal) history of the American Constitution’s formative decades

When the US Constitution won popular approval in 1788, it was the culmination of thirty years of passionate argument over the nature of government. But ratification hardly ended the conversation. For the next half century, ordinary Americans and statesmen alike continued to wrestle with weighty questions in the halls of government and in the pages of newspapers. Should the nation’s borders be expanded? Should America allow slavery to spread westward? What rights should Indian nations hold? What was the proper role of the judicial branch?

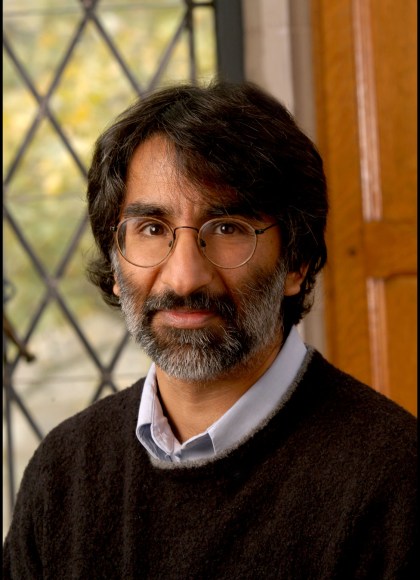

In The Words That Made Us, Akhil Reed Amar unites history and law in a vivid narrative of the biggest constitutional questions early Americans confronted, and he expertly assesses the answers they offered. His account of the document’s origins and consolidation is a guide for anyone seeking to properly understand America’s Constitution today.

-

“Deeply probing, highly readable… insightful, and at times surprising… Amar strongly suggests that America as a whole—through its great national conversation—did more to draft the Declaration of Independence than Jefferson, and more to write the Constitution than Madison… In addition to educating Americans engaged in discussion about their rich constitutional legacy, the book has a generous spirit that can be a much-needed balm in these troubled times.”New York Times

-

“The rarest of things—a constitutional romance. Amar, an eminent professor of law and political science at Yale, has great affection for his subject as a text that is worthy of loving engagement by scholars and the public at large.”Washington Post

-

"Fascinating… A masterly synthesis of history and law… Readers of The Words That Made Us will rightly marvel at its breadth and depth and at Mr. Amar’s scholarly acumen."Wall Street Journal

-

“Amar argues in this probing account that the United States Constitution emerged out of conversations and debates among the framers—and that those conversations continue to this day.”New York Times Book Review (Editor's Choice)

-

“Amar’s fresh and fascinating book focuses on the explosion of impassioned discourse that culminated in, and followed, the ratification of the U.S. Constitution. As the title suggests, the book elevates the importance of dialogue and debate in cementing American identity.”Christian Science Monitor

-

“The best book on the subject in many years… A fresh look at the ideas that shaped the Revolution, constitutional framing, and early republic… A book both popular and learned… a book not only of a scholar but a patriot. If widely read, it may make the difficulty of finding appropriate professional historians to teach our children less of a threat to our common future.”Law & Liberty

-

“Amar’s expert knowledge of the Constitution does not inhibit his ability as a wordsmith to tell this story in a manner that honors the complexity of the story and remains accessible to a broad range of readers. Every patriotic American should read this fascinating history in order to better understand our founding document (The Constitution) and the history that led our ancestors to wage war against England and then against the naysayers who were opposed to the development of a strong central government.”Roanoke Times

-

“Dazzling… Against modern historians and legal scholars who condemn the constitutional order as a bulwark of elite dominion, Amar advances a neo Federalist defense of it as a deeply democratic, if imperfect, blueprint for stable liberty. This is no arid exercise in legal theory: Amar ties searching constitutional analysis into a gripping narrative of war, popular tumults, political intrigue, and even fashion, highlighted by vivid profiles of statesmen.”Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

“A page-turning doorstop history of how early American courts and politicians interpreted the Constitution. A Yale professor of law and political science, Amar—who points out that most historians lack training in law and most lawyers are not knowledgeable enough about history—delivers a fascinating, often jolting interpretation… Brilliant insights into America’s founding document.”Kirkus (starred review)

-

“An audacious review of the Constitution’s origins, growth, development, and implementation, and the experiences and exchanges that produced its core principles and precedents… Amar’s multifaceted treatment of the start of the U.S. constitutional project illustrates much about our historical memory and demonstrates that there is far more to the constitution than the document itself.”Library Journal (starred review)

-

“Akhil Amar, one of America’s greatest constitutional teachers, has written one of America’s greatest constitutional histories. Amar’s unique brilliance as a constitutional lawyer and historian combine to create a riveting narrative history of the American idea that will illuminate and inspire readers for generations to come.”Jeffrey Rosen, President and CEO, National Constitution Center

-

“This masterpiece of a book reveals Akhil Amar to be the greatest constitutional historian of his generation. He brilliantly shows, for example, how George Washington got everything he wanted at the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention, while geniuses like Madison, Hamilton, Wilson, and Franklin all came up short. This book will be the canonical account of the birth of our Constitution and our early years as a nation for decades to come.”Steven Gow Calabresi, Clayton J. & Henry R. Barber Professor, Northwestern Pritzker School of Law

-

“With characteristic insight and wit, Akhil Amar brilliantly revives the classic constitutional history of the United States for a twenty-first-century nation. Deftly telling the story of the birth of the American constitutional system of government, Amar confronts the founders’ failures and successes with admirable frankness.”Mary Sarah Bilder, Founders Professor, Boston College

-

“Without princes or priests to impose it from above, America's Constitution evolved from an ongoing public conversation. In this timely and illuminating volume, constitutional historian Akhil Amar superbly unpacks the meaning of those words that continue to matter from the founding era. Highly recommended.”Edward J. Larson, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Summer for the Gods

-

“Akhil Amar masterfully tracks eighty years of words (and images)—urgent, sometimes angry, but always to the point. When lawless mobs, cheered by reckless pols, roam city streets and Capitol hallways, understanding our founding conversation is more important than ever.”Richard Brookhiser, author of Give Me Liberty: A History of America’s Exceptional Idea

-

"Some see history as a series of separate events. Amar knows, and demonstrates brilliantly, that history overlaps itself, that at each stage we must find (or invent) a usable past from which to shove ourselves into the featureless future. How does one present such a complex back-and-forth use of the past to escape the past? This book shows how."Garry Wills, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Lincoln at Gettysburg

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use