By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

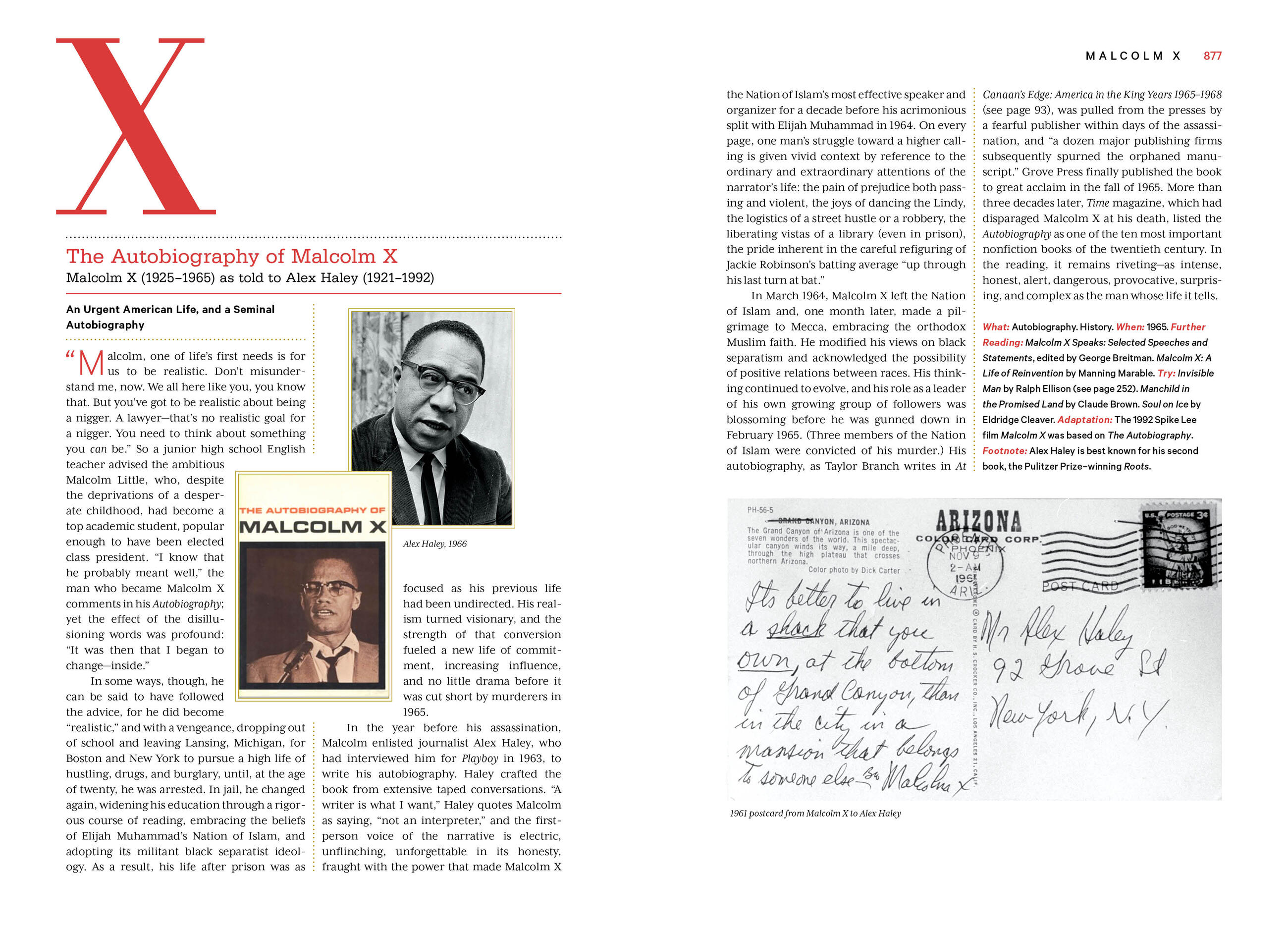

1,000 Books to Read Before You Die

A Life-Changing List

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 2, 2018

- Page Count

- 960 pages

- Publisher

- Workman Publishing Company

- ISBN-13

- 9781523504459

Price

$40.00Price

$50.00 CADFormat

Format:

Hardcover $40.00 $50.00 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 2, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“The ultimate literary bucket list.” —The Washington Post

“If there’s a heaven just for readers, this is it.” —O, The Oprah Magazine

Celebrate the pleasure of reading and the thrill of discovering new titles in an extraordinary book that’s as compulsively readable, entertaining, surprising, and enlightening as the 1,000-plus titles it recommends.

Covering fiction, poetry, science and science fiction, memoir, travel writing, biography, children’s books, history, and more, 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die ranges across cultures and through time to offer an eclectic collection of works that each deserve to come with the recommendation, You have to read this. But it’s not a proscriptive list of the “great works”—rather, it’s a celebration of the glorious mosaic that is our literary heritage.

Flip it open to any page and be transfixed by a fresh take on a very favorite book. Or come across a title you always meant to read and never got around to. Or, like browsing in the best kind of bookshop, stumble on a completely unknown author and work, and feel that tingle of discovery. There are classics, of course, and unexpected treasures, too. Lists to help pick and choose, like Offbeat Escapes, or A Long Climb, but What a View. And its alphabetical arrangement by author assures that surprises await on almost every turn of the page, with Cormac McCarthy and The Road next to Robert McCloskey and Make Way for Ducklings, Alice Walker next to Izaac Walton.

There are nuts and bolts, too—best editions to read, other books by the author, “if you like this, you’ll like that” recommendations , and an interesting endnote of adaptations where appropriate. Add it all up, and in fact there are more than six thousand titles by nearly four thousand authors mentioned—a life-changing list for a lifetime of reading.

“948 pages later, you still want more!” —THE WASHINGTON POST

“If there’s a heaven just for readers, this is it.” —O, The Oprah Magazine

Celebrate the pleasure of reading and the thrill of discovering new titles in an extraordinary book that’s as compulsively readable, entertaining, surprising, and enlightening as the 1,000-plus titles it recommends.

Covering fiction, poetry, science and science fiction, memoir, travel writing, biography, children’s books, history, and more, 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die ranges across cultures and through time to offer an eclectic collection of works that each deserve to come with the recommendation, You have to read this. But it’s not a proscriptive list of the “great works”—rather, it’s a celebration of the glorious mosaic that is our literary heritage.

Flip it open to any page and be transfixed by a fresh take on a very favorite book. Or come across a title you always meant to read and never got around to. Or, like browsing in the best kind of bookshop, stumble on a completely unknown author and work, and feel that tingle of discovery. There are classics, of course, and unexpected treasures, too. Lists to help pick and choose, like Offbeat Escapes, or A Long Climb, but What a View. And its alphabetical arrangement by author assures that surprises await on almost every turn of the page, with Cormac McCarthy and The Road next to Robert McCloskey and Make Way for Ducklings, Alice Walker next to Izaac Walton.

There are nuts and bolts, too—best editions to read, other books by the author, “if you like this, you’ll like that” recommendations , and an interesting endnote of adaptations where appropriate. Add it all up, and in fact there are more than six thousand titles by nearly four thousand authors mentioned—a life-changing list for a lifetime of reading.

“948 pages later, you still want more!” —THE WASHINGTON POST

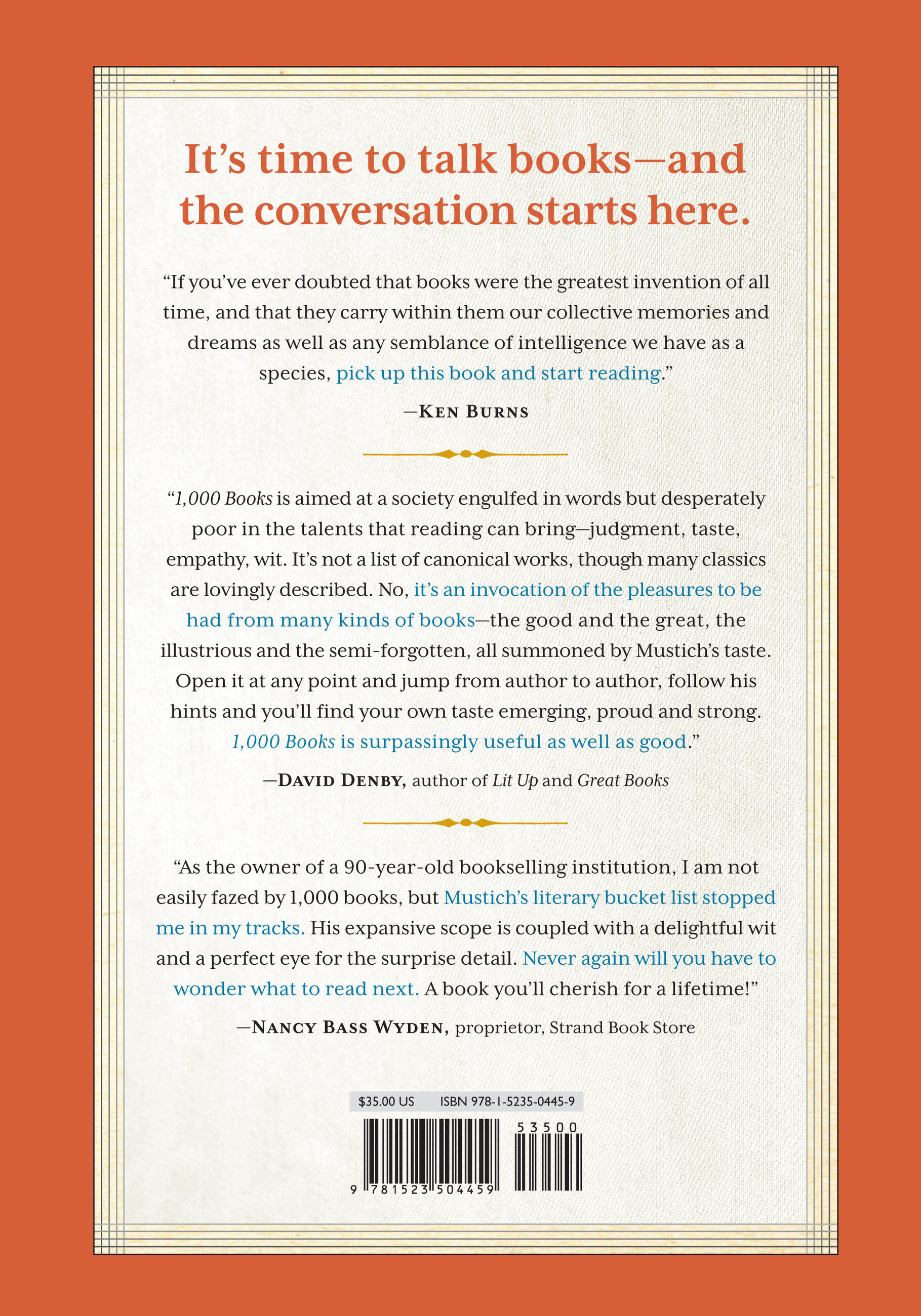

-

“If there’s a heaven just for readers, this is it.” — O, The Oprah MagazineBooklist, Starred Review "All in all, the literate public—what novelist Robertson Davies dubbed the clerisy—can only be grateful for, and awed by, this product of 14 years of reading and research…It’s hard to imagine that such a massive compendium could have been done better."—Michael Dirda, The Washington Post "Absolutely impressive…. This book is not just a source of information; it's a wellspring of wisdom, intelligence, empathy and generosity."—Ingrid Rossellini, author of Know Thyself: Western Identity from Classical Greece to the Renaissance "As the owner of a 90-year-old bookselling institution, I am not easily fazed by 1,000 books, but Mustich’s literary bucket list stopped me in my tracks. His expansive scope is coupled with a delightful wit and a perfect eye for the surprise detail. Never again will you have to wonder what to read next. A book you’ll cherish for a lifetime!" —Nancy Bass Wyden, Proprietor, Strand Book Store "Chief among the thousands of pleasures here is the delightfully erudite company of James Mustich. Look up your favorite books; find ones you don’t know; argue about the list with friends. Read!" —Jean Strouse, author, Alice James and Morgan: American Financier "James Mustich’s book is aimed at a society engulfed in words but desperately poor in the talents that reading can bring—judgment, taste, empathy, wit. The book is not a list of canonical works, though many classics are listed and lovingly described. No, the “1000 Books to Read” is an invocation of the pleasures to be had from many kinds of books—genre fiction, journalism, poetry, history, and memoir, the good and the great, the illustrious and the semi-forgotten, all summoned by Mustich’s taste. You open it at any point and jump from author to author; you follow his hints and read related works by other writers, and you find your own taste emerging, proud and strong, from Mustich’s provocations. 1,000 Books is surpassingly useful as well as good." —David Denby, staff writer at The New Yorker and author of Great Books: My Adventures with Homer, Rousseau, Woolf, and Other Indestructible Writers of the Western World "If you’ve ever doubted that books were the greatest invention of all time, and that they carry within them our collective memories and dreams, as well as any semblance of intelligence we have as a species, pick up James Mustich’s 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die and start reading." —Ken Burns "If I were as erudite, entertaining, insightful, and articulate as James Mustich, I could come up with 1,000 reasons to get his book. But here's one: Whether you're looking for something to read for personal edification or fun, for escapism or relevance, you can survey the literary world with Mustich as an experienced, enthusiastic guide. His work is an essential resource for anyone anywhere plagued by that infernal question: What do I read next?" —Bradley Graham, co-owner of Politics and Prose Bookstore

★"Mustich's informed appraisals will drive readers to the books they've yet to read, and stimulate discussion of those they have." I>Publishers Weekly, Starred Review

★"A treasure chest for book lovers everywhere" I>Library Journal, Starred Review

★"Every so often, a reference book appears that changes the landscape of its area of focus. In the case of reading and readers' advisory, this is one such book....lively, witty, insightful prose...It might be wise to invest in several copies of this wonderful meditation on life lived with and enhanced by the written word."

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use