By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

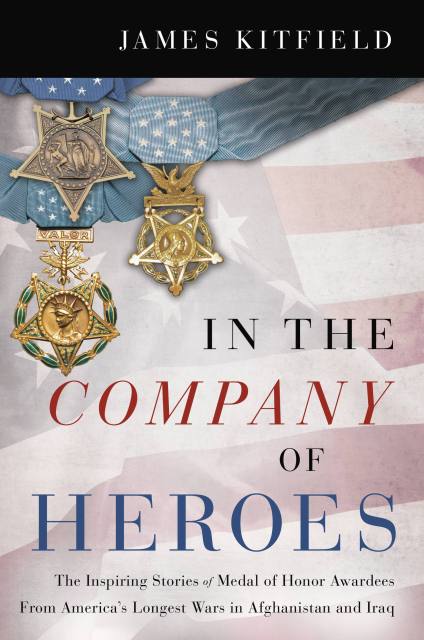

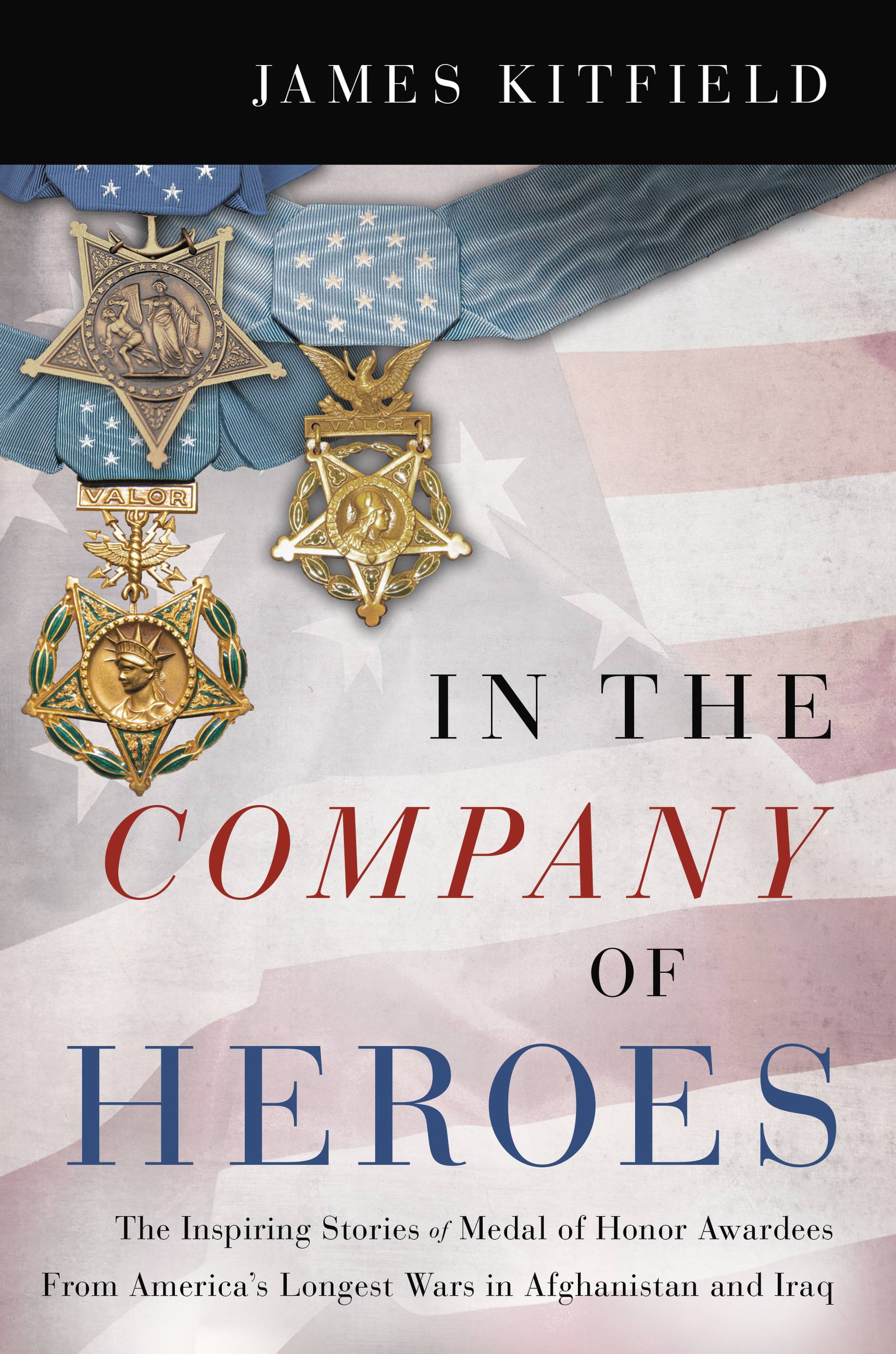

In the Company of Heroes

The Inspiring Stories of Medal of Honor Recipients from America's Longest Wars in Afghanistan and Iraq

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 31, 2021

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781546085805

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 31, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

An award-winning military journalist tells the amazing stories of twenty-five soldiers who've won the Medal of Honor, the nation's highest military award.

In the Company of Heroes will feature in-depth narrative profiles of the twenty-five post-9/11 Medal of Honor awardees who served in Afghanistan and Iraq. This book will focus on the stories of these extraordinary people, expressed in their own voices through one-on-one interviews, and in the case of posthumous awards, through interviews with their brothers in arms and their families. The public affairs offices of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the individual armed services, as well as the Congressional Medal of Honor Society, have expressed their support for this project.

Stories include Marine Corps Corporal William "Kyle" Carpenter, who purposely lunged toward a Taliban hand grenade in order to shield his buddy from the blast; Navy SEAL team leader Britt Slabinski, who, after being ambushed and retreating in the Hindu Kush, returned against monumental odds in order to try to save one of his team who was inadvertently lost in the fight; and Ranger Staff Sergeant Leroy Petry, who lunged for a live grenade, threw it back at the enemy, and saved his two Ranger brothers.

In the Company of Heroes will feature in-depth narrative profiles of the twenty-five post-9/11 Medal of Honor awardees who served in Afghanistan and Iraq. This book will focus on the stories of these extraordinary people, expressed in their own voices through one-on-one interviews, and in the case of posthumous awards, through interviews with their brothers in arms and their families. The public affairs offices of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the individual armed services, as well as the Congressional Medal of Honor Society, have expressed their support for this project.

Stories include Marine Corps Corporal William "Kyle" Carpenter, who purposely lunged toward a Taliban hand grenade in order to shield his buddy from the blast; Navy SEAL team leader Britt Slabinski, who, after being ambushed and retreating in the Hindu Kush, returned against monumental odds in order to try to save one of his team who was inadvertently lost in the fight; and Ranger Staff Sergeant Leroy Petry, who lunged for a live grenade, threw it back at the enemy, and saved his two Ranger brothers.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use